Hedge funds have sold the equivalent of almost half a bn barrels of crude oil and refined products in the last six weeks, as worries about slowing demand replaced earlier concern over sanctions on Iran.

Hedge funds and other money managers cut their combined net long position in the six major petroleum futures and options contracts by another 108mn barrels in the week to November 6.

Portfolio managers have sold 479mn barrels of crude and products since the end of September, the largest reduction in any six-week period since at least 2013 and probably the largest ever in a comparable time-frame.

Funds now hold fewer than four bullish long positions for every short bearish one, down from more than 12:1 at the end of September and the lowest ratio since August 2017.

Most of the adjustment has come from the long side of the market, as formerly bullish hedge funds liquidate positions accumulated in the second half of 2017 and earlier in 2018.

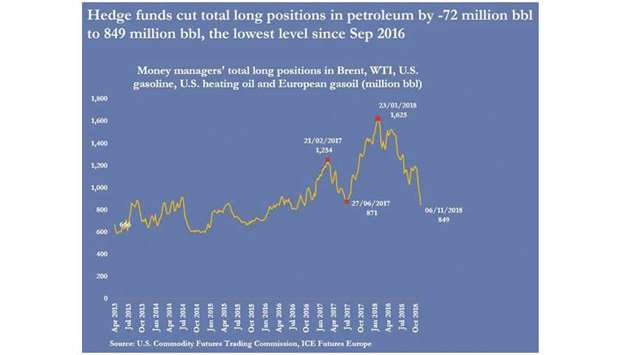

The number of bullish long positions has fallen to just 849mn barrels, from 1.195bn six weeks ago and a record 1.625bn at the start of the year.

Bullish positions are now at the lowest level since September 2016, according to an analysis of position data published by regulators and exchanges.

But some fund managers have begun to turn outright bearish, with short positions now up to 228mn barrels from just 96mn barrels six weeks ago.

Heavy selling by funds has helped push oil prices down more than $15 per barrel (17%) since October 3.

And since most hedge fund positions are held in contracts near to maturity, the selling has had a disproportionate impact at the front end of the futures curve, pushing crude futures prices deep into contango.

Portfolio managers have reacted to an increasingly bearish news flow amid signs the oil market has passed its current cyclical peak.

Production growth is accelerating while consumption growth is slowing — conditions reminiscent of cyclical peaks in mid-2014 and mid-2008.

Opec members and their allies have been boosting output, partly in response to political pressure from the White House.

US shale producers have ramped up their own production at the fastest rate on record, with output up by more than 2mn barrels per day in the 12 months to August.

And the United States has issued waivers to allow some of Iran’s most important customers to continue buying oil despite the reimposition of sanctions, waivers that have been more generous than previously expected.

At the same time, oil traders have become increasingly worried about the possibility of a global economic slowdown or even a recession hitting oil demand next year.

And there are signs higher oil prices have begun to prompt increased interest in fuel efficiency and other behavioural changes among consumers, with consumption growth slowing from rapid rates in 2016 and 2017.

With the market on course for oversupply, oil prices needed to fall from recent highs to curb production, boost consumption and avert a large buildup in excess inventories in 2019.

Price falls have already begun to enforce the rebalancing process, with Opec and its allies starting to discuss production cuts of as much as 1mn barrels per day. Some observers have expressed surprise at how quickly market commentary has shifted from the need for more oil to concerns about oversupply, but the speed of the shift is not unusual.

In 2008 and 2014, market commentary shifted from fears about undersupply to oversupply within three to four months around the peak, and something similar appears to be happening this time.

John Kemp is a Reuters market analyst. The views expressed are his own.

graph 3