The Philippines’ rich history of political and socially conscious cinema was on display this week at Asia’s largest movie gathering, shadowed by the controversy over President Rodrigo Duterte and his deadly drug war.

Busan International Film Festival delivered a record number of features from the nation, which has a turbulent political past, widespread poverty and is in the international eye due to condemnation of the president’s narcotics crackdown.

The 19 offerings gave an unflinching dive into the country’s frailties and obsessions, including its political landscape. As the event that closes today kicked into high gear on October 5, Duterte’s leadership was fiercely criticised by Filipino director Mike de Leon, whose latest was screened at BIFF.

“My country has hit rock bottom...again,” he wrote on Facebook. “We have de facto become a dictatorship again, in everything but name.”

He was referring to the rule of Ferdinand Marcos who used martial law from 1972-1981 to shutter the legislature, muzzle the free press and jail or kill opponents.

While Duterte has sky-high approval among Filipinos, according to polls, opponents charge he has resorted to similar abuses since taking power in 2016.

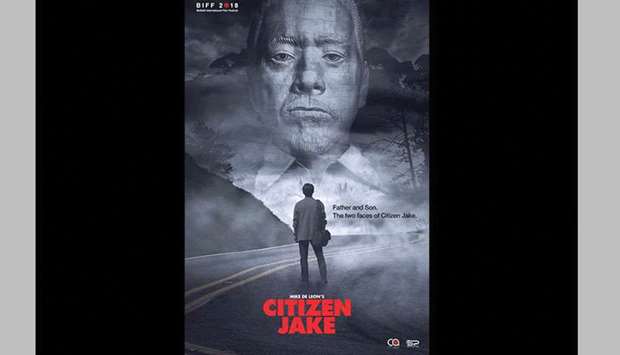

De Leon, whose politically pointed family melodrama

Citizen Jake made its international premiere at Busan, said he made the picture to document the nation’s condition.

It is an “indictment of the unchanging nature of Philippine society that, in my opinion and as shown in the film, is almost irredeemably damaged,” he posted.

Duterte, however, had his supporters among Filipino film-makers who made the trip to Busan, including Cannes-honoured Brillante Mendoza.

The director best known for his hyper-real depictions of the Philippines’ dark underbelly of crime and poverty has defended Duterte’s leadership and effort to eliminate drugs from the nation.

His Netflix series Amo sparked controversy earlier this year with a tale of a young man swept away by his involvement in narcotics that critics called an argument in favour of Duterte’s crackdown.

“Cinema is addictive. It can change your life,” Mendoza told journalists.

“It became clear to me that films have a purpose. They can make a difference.”

The directors were reared in a nation with a deep tradition of movies that plunge into its troubled past and current social ills like sex trafficking.

“Our films concentrate on our political concerns and on family,” said Filipino film historian Tito Valiente. “They have followed our path from colonialism to nationalism.”

A Filipino retrospective at Busan also included a rare screening of Lamberto V Avellana’s class-war themed classic A Portrait of the Artist as

Filipino (1965).

Audiences at the festival, known for an open atmosphere where fans can connect with stars, also saw the world premiere of the triptych “Lakbayan” which touches on the issues of illegal land grabs and the plight of poor farmers.

A host of filmmakers and stars from the nation travelled to South Korea’s second largest city, including actors Christopher de Leon and Sandy Andolong.

BIFF also saw a series of seminars looking at the history and future of Philippine cinema, which Philippines officials now plan to take to festivals around the world.

“To understand our cinema you need to understand what the Philippines is,” said veteran actor Joel Torre, part of the nation’s delegation to BIFF.

“We are a very mixed culture,” he added.

The official poster of Citizen Jake.