Being home to Europe’s biggest rock collection has finally come in handy for Sweden amid the global race for the scarce metals that power electric cars. For more than a century, the Nordic nation has accumulated thousands of ore samples — so many that if they were laid end to end, they’d stretch from Minneapolis to Mexico and beyond.

They’re stored at the Geological Survey of Sweden’s drill core archive, where visitors pay 1,000 kronor ($110) a day to examine rocks stashed in rows and rows of wooden crates in hopes of spotting rich deposits of minerals like cobalt, the bluish-grey mineral that’s got carmakers in a tizzy. Over 3,000 kilometres of ore samples dating back to the early 20th century are stashed in the library.

Initially extracted in search of base metals like iron ore or copper, the rocks are getting a second look because Sweden is a rare part of Europe that boasts all the raw materials used to make batteries. “If you’re in mineral exploration, this is really the only place to be,” said Amanda Scott, a geologist who helps mining companies find the best spots for minerals like cobalt, lithium and vanadium.

The library is about a nine-hour drive north of the capital Stockholm, nestled deep in the forests of the Lapland province. The collection has long drawn geologists fascinated by the Baltic Shield, the segment of the Earth’s crust that encompasses Sweden and is rich in Precambrian crystalline rock, among Europe’s oldest.

But the focus has changed as the global hunt for battery mineral resources prompts miners and geologists to re-examine old exploration sites in places like Canada, western Australia and Finland, currently the only place in the European Union that extracts cobalt.

A rock sample stands in its case. Bringing Sweden into the fold is important for European carmakers because at the moment, 60% of global production centres on Democratic Republic of Congo, where corruption is rampant and Amnesty International has chronicled the use of child labour at some artisanal mines.

Most of Congo’s cobalt, meanwhile, is refined in China, which has dominated the battery supply chain. If exploited, Sweden’s cobalt reserves could power more than 4mn vehicles, something the government is betting will revive the mining industry after this decade’s commodity slump stifled new projects.

Last year, it issued a record number of exploration permits for battery metals, including 48 for cobalt, more than all the preceding years this century combined. “Sweden won’t reach the levels that Congo has, but it can definitely play a part in the European market,” said Par Weihed, a professor in ore geology and pro vice chancellor at the Lulea University of Technology in northern Sweden.

“There is very good geological potential for basically all critical metals.” In a country that spans 1,500 kilometres from top to bottom, the drill-core library is the best place to start the exploration process. The collection was drawn from 18,000 drill holes and the cylindrical ore samples span 3,000 kilometres, six times longer than the US Geological Survey’s research centre in Denver.

Before spending millions on exploratory drilling, miners can take lengthwise sections of existing ore for metallurgical testing — grinding it down to see how much of a desired mineral they can separate out to make concentrate. Catalogued rock samples at the archive.

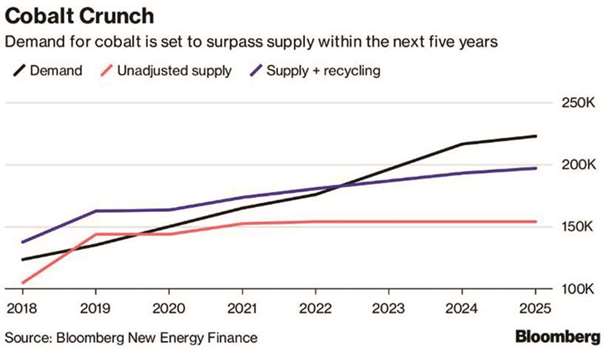

Until recently, cobalt — used to stabilise the molecular structure of lithium-ion batteries — was only worth excavating as a byproduct of things like copper and nickel. But its price has soared 140% in the past two years as carmakers from Tesla to BMW announced fleets of electric cars that will tip demand above supply in just a couple of years.

That shift has been keeping Scott busy. She opened a consultancy steps away from the drill core library in 2016 to help miners figure out where to start on-site exploration, and her client base has quadrupled since. Australia’s Talga Resources, for one, used the archive to identify four possible cobalt hot spots in northern Sweden, including at the Kiskama mining site that had been a focal point for copper and gold mining in the 1970s and 80s.

Some of the 95 samples dug out during that time were re-examined for their cobalt content. Geologist Amanda Scott examines a bag of samples at her office. “This is Sweden’s biggest opportunity for a real cobalt project,” Martin Phillips, Talga’s chief operating officer, said on the sidelines of the Euro Mine Expo trade fair in Skelleftea, Sweden, in late June. While the grade of cobalt at Kiskama is poorer than Congo’s, it’s easier to extract from the surface using open-pit mining because the ore body is a lot wider, he said.

At about 19,000 tonnes, Sweden’s known reserves are nonetheless meagre compared with Congo’s 3.5mn. Even Finland has resources amounting to about 446,000 tonnes, although not all of that may be economically feasible to extract.

.