One man savagely attacks another, killing him on the spot then dousing the corpse with gasoline and setting it on fire. Opening a film with a scene like that would be business as usual for any number of directors, but Japan’s Hirokazu Kore-eda is not one of them.

Kore-eda, who won this year’s Cannes Palme d’Or for his latest film, Shoplifters, is known as Japan’s nonpareil humanist filmmaker, not someone who usually has murder on his cinematic mind.

But Kore-eda is also a director who goes where his interests take him, no matter how unexpected; his filmography includes dramas like 2009’s Air Doll, which has an inflatable toy as its centre of interest.

And because the filmmaker is who he is it figures that Third Murder is not your standard John Grisham knockoff legal thriller but a meditation on the elusiveness of truth and its relation to guilt, innocence and justice as it is administered by the Japanese legal system.

Is the murder of a Yokohama factory owner we have witnessed with our own eyes the murder that actually happened? How much can we believe what we think we’ve seen, or, for that matter, what people claim they saw?

Yet because the sowing of disturbing confusion is Third Murder’s” aim, experiencing it can be as frustrating as it is fascinating, maybe even more so.

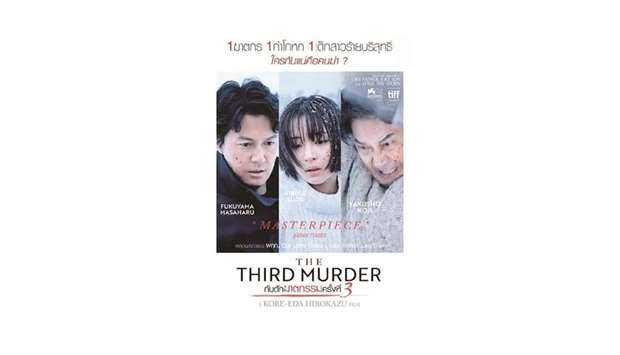

Though the story is not business as usual for him, Kore-eda has used two of his previous actors in key roles, starting with Masaharu Fukuyama, who was the put-upon parent in the director’s exceptional Like Father, Like Son.

Here Fukuyama plays high-powered defence attorney Shigemori, called in by a colleague to consult on the defence of Misumi (Koji Yakusho), the man who has confessed to the murder of the factory owner that’s the film’s starting point.

An all-business type who reminds an associate that they are defending Misumi, not becoming his friend, Shigemori thinks of himself as a pragmatist who cares not about the truth but about what a winning strategy might be, a belief system defending Misumi is going to test.

Giving the case an unusual wrinkle is a unexpected connection between defendant and lawyer that dates back 30 years.

At that time Misumi was convicted of murdering two other men (hence the film’s title), but Shigemori’s father, who was the trial judge, sentenced him to 30 years in prison instead of death. In fact, Misumi was recently released from prison when the factory owner, who was his boss, was killed.

Much about Misumi and his confession to murder and robbery seem straightforward, but the accused has the unnerving habit of frequently changing details of his confession, something which makes putting a defence together challenging.

In fact it is a tribute to Yakusho’s performance that apparently straightforward Misumi comes off as an elusive, enigmatic character, difficult to pin down and harbouring eccentricities like a deep passion for peanut butter.

Because of the vagaries of the Japanese legal system (one of Kore-eda’s themes) it goes harder on a murderer if robbery is just an afterthought and not the motive, so Shigemori works diligently to establish a grudge against the factory owner as the reason.

In line with this, the attorney pays a pro-forma visit to the murder victim’s angry widow, and also pays attention to the dead man’s daughter Sakie, played by Suzu Hirose, outstanding in Kore-eda’s earlier Our Little Sister.

A woman who walks with a pronounced limp, Sakie turns out to be as difficult to pin down as Misumi, telling different stories to different people about where that limp came from.

Also figuring in the narrative are Shigemori’s own family, including a teenage daughter who is acting out, and his father the judge, who pays his son a visit and is given to making provocative comments like “psychiatry is not a science, it’s fiction” and “Some people are more beast than human.”

Kore-eda is too polished a filmmaker for The Third Murder not to be of interest, but its focus is finally too fuzzy to compel the way the best of the director’s work does.

With what happened on that fatal night and why increasingly difficult to know, we are forced to agree with the character who says “we’ll never know which is the truth,” but that is not the most satisfying place to be. – Los Angeles Times/TNS

ent