Ils sont les meilleurs. Sie sind die Besten. These are the champions!

At least they are if you squint a little. When Liverpool and Real Madrid walk out at the Olympic Stadium in Kiev, neck hairs prickling to the wonderfully overblown strains of Tony Britten’s choral Champions League theme, they will do so in the capacity of genuine European aristocracy.

By the end of Saturday night these two clubs will have won five of the past 14 Champions Leagues between them and almost a third of all European Cups since the competition was born more than half a century ago.

There is a purity even in the prospect of meringue white versus Anfield red, a skein of emotional authenticity in the flags, the songs, that shared folk memory of so many other floodlit triumphs.

There is, of course, another side to this. Some will question the right of either team to proclaim themselves the best in Europe when between them these two champions in waiting finished a combined 42 points behind Manchester City and Barcelona in the weekly grind.

Not that there’s anything new in this. The last reigning domestic champions to lift Europe’s shiniest trophy were the peak Messi-Pep Barcelona of 2011, evidence either of the dilution of the competition’s purity or of its sheer depth of quality, depending on where you choose to stand.

This time, though, the disjunct is pronounced. For Madrid a fourth title in five years would install this team as unassailable masters of the modern age. At home they have two league titles in the past decade. Liverpool haven’t been champions of England in more than a quarter of a century. Die Meister. Die Besten. Les grandes équipes!

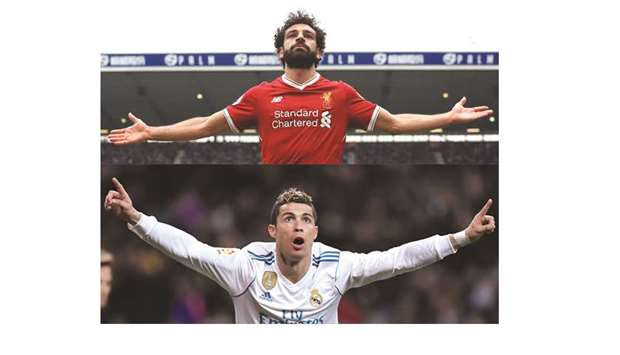

And yet for all the gripes there are certain unassailable qualities in both these finalists, peaks that have been beyond the rest of Europe this year. Not least that visceral commitment to attack embodied in the headline acts Cristiano Ronaldo and Mohamed Salah.

Nobody else has scored more goals in the competition this season than these two teams. Nobody else has had more shots on target or attacked with such cavalier conviction. Liverpool have scored or conceded 53 goals in the tournament proper en route to Kiev, Madrid 45.

By way of comparison, Manchester United conceded five and scored 13 across eight games in the course of a meek last-16 exit that felt as if it came from another sporting age altogether.

Attacking football is in vogue, state of the art among winning teams, although not simply the annihilating slow death of possession football. Liverpool are 10th when it comes to average minutes in possession of the ball this year, Madrid fifth. Victory has instead come through periods of sustained attacking heat, a way of playing that some have called the surge or the blitz.

Liverpool did not win in Germany, Portugal and Manchester by wearing their opponents down but by conjuring up those famous attacking spells, moments where they simply flip the switch and enter the Red Zone, a team playing through a kind of synchronised rage.

Madrid were almost laughably fortunate in the second leg of their semi-final against Bayern Munich at the Bernabéu, hanging on as the ball trickled or dribbled away from the vital touch so often that there was a kind of hysteria in the stands by the end. But that tie, like the previous round against Juventus, was won by trusting in the cutting edge at the other end, the absolute conviction that at some point those strengths will tell. To borrow a line from Gary Player, the more Real Madrid keep on winning the Champions League in haphazard attacking fashion the luckier they seem to get.

Either way, the vocal majority who seemed so underwhelmed by the dogged, reactive football on show in Saturday’s FA Cup final can at least be assured of something else in Kiev. There will be extremes of attacking intent. There will be defensive slackness. There will be goals.

Talking of which: enter the big two. It is, of course, misguided to obsess over individuals in what is more than ever a team sport. But this is unlikely to stop anyone doing it – relentlessly, and with an increasing reverence for the power of the star player, a sport of endless close-ups and grand-scale personality obsession.

The Champions League final dishes up a little more in the way of ultimacy here, with a meeting of Ronaldo and Salah: football’s reigning golden goal-dalek, the current owner of the Ballon d’Or, versus the Premier League’s own man of the season.

It has been almost too easy to pitch this final as a shootout between two players who have 25 Champions League goals between them. But sometimes you just have to go with it, not least when both embody and enact the most extreme strengths of their own team; and when they have a little more in common as players than might at first seem the case.

Zinedine Zidane has already announced that he wouldn’t take Salah in his Madrid team. It is hard to imagine him saying anything else on the eve of the final, just as there is no real comparison to be made here, at least not yet. Ronaldo is an all-time phenomenon, remarkable for his sustained, relentless productivity. Salah has been operating somewhere close to this for nine months now.

But still, we are in the late days now of the Messi-Ronaldo godhead, a conjoined supremacy that has been soundtracked by a rolling sub-debate about succession, about the next of the next-besters. Salah’s 42 goals this season (to Ronaldo’s 41) have elevated his status, a newbie face among that raft of pretenders.

In terms of style – left-footed, jinky, shaggy-haired – Salah has most often been compared to Messi. But the fact is that he is probably closer to Ronaldo. Both run relentlessly, popping up in the top five attackers for metres covered in the Champions League this season.

Like a mid-20s Ronaldo, Salah is a power-runner with wonderfully quick feet and the ability at his best to basically make the game up in front of him. Salah is yet to reach anywhere near the same heights. But in his best moments he looks a bit like a product of some advanced gene-splicing Ronaldo-Messi experiments: the body of a shaggy-haired, left-footed jinker, but the direct style of a sprinter, a cutting edge rather than a playmaker.

In Kiev, Salah and Ronaldo will once again be key to the attacking tempo of the competition’s two highest scoring teams. There has been a slight adaption with Madrid. These days they like to push you back and keep possession, to load balls into the box knowing Ronaldo will eventually find the tiny pocket of air he requires to combination punch the ball into the back of the net.

With Liverpool the best moments have all been about the surge and the blitz, led so often by Salah. The Olympic Stadium was originally known as the Red Stadium of Trotsky, and after that as the just the Red Stadium. The ability of the team and their fans to turn the air red on Saturday night, to generate that shared driving energy, will be key to Liverpool’s chances. Either way, it promises to be a thrilling, extreme and in its own way entirely apt meeting of the knockout cavaliers.

Cristiano Ronaldo and Mohamed Salah