Russia’s economy has long moved past the government’s 1998 debt default, but president Vladimir Putin may never get over what a witness to the events calls the “terrible humiliation.”

While Russia’s balance sheet is now the envy of emerging markets, the trauma still shapes the personnel choices and the tilt of economic policy toward fiscal conservatism.

From central bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina to Anton Siluanov, reappointed as finance minister on Friday, today’s decision makers are part of a generation that, having “lived through the ’98 default as young adults, is marked forever,” said Martin Gilman, who led the International Monetary Fund’s Russia office during the debt crisis.

“Pro-growth fiscal policy won’t happen as long as this group of people remains the ones Putin would want to see running the economy,” he said in an interview. The president knows “they were tested by fire” and won’t make the same mistakes again, according to Gilman, now a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

Putin, who became prime minister a year after the debt debacle, before being elected president in 2000, hasn’t veered off course when it comes to fiscal probity, despite revisiting many of Russia’s other priorities since then. The country now stands out in emerging markets as nations from Argentina to Turkey buckle under the pressure of currency weakness and inflation.

Helped by years of rising oil prices, Russia was able to cut borrowing and paid off its remaining debt to the Paris Club of creditors ahead of schedule. Despite rounds of Western sanctions, non-residents now hold a record share of sovereign ruble securities.

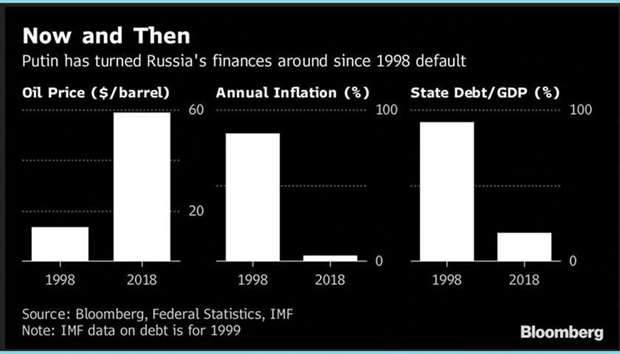

In 1998, as crude collapsed near $10 a barrel, the Russian government defaulted on $40bn of domestic debt, the bulk of which was held by foreign investors.

Under IMF projections, Russia’s state debt was at just over 17% of gross domestic product in 2017 and will stay around 20% through 2023, compared with over 90% in 1999. As a share of foreign-exchange reserves, Russia’s external financing requirements – the sum of its current-account balance and foreign debt maturing within the next 12 months – is the strongest in emerging markets, according to Capital Economics.

Meanwhile, the rouble is the only currency in developing nations to gain against the dollar this month. Besides Siluanov, who was also promoted to serve as first deputy prime minister, the cabinet picks unveiled on Friday included other veterans of 1998.

Tatiana Golikova, who was a Finance Ministry official during the default, became a deputy premier for education, health and social policy.

Alexei Kudrin, Russia’s finance minister during Putin’s first decade in power, will replace Golikova as the head of the Audit Chamber, the state’s budget watchdog.

It’s “a very defensive lineup from Putin,” said Timothy Ash, a senior emerging-market strategist at BlueBay Asset Management in London. He’s “taking no chances, and not suggesting a much needed radical reform agenda.”

The safeguards built up during the oil boom years have served Russia well during the two major crises of Putin’s reign. The $458bn stockpile of international reserves, now near a four-year high, has also taken on strategic importance as a buffer during Putin’s duels against the West.

Thanks to more far-reaching changes introduced after the crash in energy prices four years ago, the government is on track for its first budget surplus since 2011. Despite a rally in crude, a fiscal mechanism only allows spending increases by the amount of additional non-oil revenues while channelling the excess energy income into a sovereign wealth fund.

The downside is that Russian education, health care and infrastructure remain underfunded. Re-elected in March to a record fourth term, Putin has promised to accelerate sluggish economic growth and deliver a “decisive breakthrough” in living standards. But Nabiullina has repeatedly warned that the economy won’t grow faster than 2% without structural reforms.

“The fiscal policy stance is set to remain tight despite the oil-price recovery,” Morgan Stanley economists including Pasquale Diana and Alina Slyusarchuk said in a report.

“Only in 2019 do we expect the Finance Ministry to have a chance to support growth.”

.