The search for offshore oil begins with a boom.

Before the oil rigs arrive and the boring begins, operators need to fire intense seismic blasts repeatedly into the ocean to find oil deposits.

For decades, environmental rules that protected whales and other marine life from this cacophony have limited the location and frequency of these blasts — preventing oil companies from exploring, and therefore operating, off much of the American coasts.

Now those safeguards are being dismantled.

The push to change seismic survey rules has not attracted the same public attention as the Trump administration’s interest in opening coastal waters to dozens of new drilling leases or downsizing protected marine areas. But it could have wide implications beyond enabling new oil operations.

Winding their way through Congress are two bills that supporters say would create jobs, reduce permitting delays and clear the way for naval activities and coastal restoration.

But environmentalists call them a thinly veiled oil industry wish list that would upend established protections and fast-track the permitting process for oil exploration off the Atlantic, much of Alaska and off California.

“So much legislation like this just goes under the radar,” said Rep. Jared Huffman, D-Calif., ranking minority-party member of the House Subcommittee on Water, Power and Oceans. “It’s a scorched earth effort right now across the whole of federal public policy to give things away to the oil and gas industry.”

The bills have passed committee and could go to a full vote any day.

They target core provisions of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which regulates seismic blasts used to locate oil and gas. The noise, scientists say, can disorient and damage the hearing of whales and dolphins so badly that they lose their ability to navigate and reproduce.

The bills follow other subtle undoings that opponents have linked to prioritising energy over conservation. President Donald Trump, in his budget proposal, had pushed to cut all funding for the Marine Mammal Commission, an advisory group that provides scientific expertise during the review process for proposed oil activities. (Funding was restored in last month’s budget deals.)

“It’s like burning down the jail, eliminating all the laws and then shooting the court and jury,” said Richard Charter, senior fellow at the Ocean Foundation. “This is a time of setbacks, but undoing the Marine Mammal Protection Act is one of the most damaging things that Congress could possibly do right now.”

Rep. Mike Johnson, R-La., who introduced the Sea Act, rejected assertions that his bill was driven by oil. In a statement, his office said “there’s a large campaign of misinformation against the Sea Act filled with misleading rhetoric. The Sea Act makes absolutely no changes to the protections established by the (Marine Mammal Protection Act). Any suggestion otherwise is blatantly false.”

The changes would eliminate “cross-agency, duplicative regulations” that cause permitting delays, said his spokeswoman, Ainsley Holyfield. They were introduced after Johnson discovered “this very issue had halted coastal restoration efforts in Louisiana and naval operations off the coast.”

Johnson’s proposals are also included in a broader bill by House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, R-La., that “overhauls federal lands energy policy to promote expanded exploration, development and production of oil, gas and wind resources,” according to the House Committee on Natural Resources.

This push in Congress comes after Trump’s executive order last year, which reversed an Obama administration decision that denied six companies seeking permits to conduct testing in the Atlantic. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has called for seismic tests to get the new data needed for energy expansion.

“Allowing this scientific pursuit enables us to safely identify and evaluate resources that belong to the American people,” Zinke said. “This will play an important role in the president’s strategy to create jobs and reduce our dependence on foreign energy resources.”

The issue has been tricky for some Republicans, particularly those representing coastal districts where offshore drilling is unpopular.

Some have spoken up. Rep. John Rutherford, R-Fla., in a bipartisan letter last year, said seismic testing posed a direct threat to economies that rely on fishing, tourism and recreation.

“We hear from countless business owners, elected officials and residents along our coasts who recognise and reject the risks of offshore oil and gas development,” said the letter, signed by dozens of Congress members. “It harms our coastal economies in the near term and opens the door to even greater risks from offshore oil and gas production down the road.”

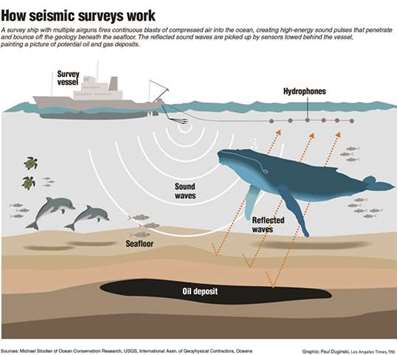

Seismic surveying involves a ship firing blasts of pressurised air to create powerful sound pulses that penetrate beneath the seafloor. The sound waves that bounce back are picked up by sensors, painting a picture of potential oil deposits. Below the surface, the explosions sound like bombs going off every 10 to 15 seconds and can be heard as far as 1,500 miles, audio recordings show.

They threaten a number of species, including the blue whales that visit California’s coast and the dwindling number of right whales in the North Atlantic. Whales aren’t easy to study — they’re difficult to count, hard to track and impractical to examine. But by analysing their behaviour, scientists have found that blasts can throw off their ability to find food, avoid predators and find mates.

Oil and gas supporters say the research isn’t conclusive and that the best available science does not indicate that surveying damages the overall marine population.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act — signed by President Richard Nixon in 1972, at a time when protecting marine life from overfishing and overhunting was a priority across party lines — makes it illegal to harm or kill a whale, dolphin, seal, manatee, sea otter or polar bear without a permit, even if done inadvertently.

Obtaining a seismic testing permit under the law can take years and requires companies to show that their operations will have the “least practicable impact” on only “small numbers” of animals. Mitigation measures are strict and err on the side of precaution; ships have to turn off the blasts if whales are seen nearby.

The new bill drops the “small numbers” and “least practicable impact” conditions, and requires automatic approval of a permit if a review is not complete within 120 days. It deletes the requirement for a permit to be contained within a specific geographic region, expanding it to most anywhere off any coast.

Industry groups such as the International Association of Geophysical Contractors endorse the changes as much-needed modernisation of a law that has “hampered (seismic surveying) by extreme environmental advocacy groups that abuse existing regulatory and litigation processes.”

Words like “negligible impact” and “small numbers” are ambiguous and would create an approval system that is biased and can delay permits for years, said the group’s president, Nikki Martin. “This is unwarranted and represents a complete bureaucratic breakdown in an otherwise straightforward process by federal agencies.”

Industry groups say seismic surveys have been safely conducted around the world for decades. Technology today is even more advanced, they say, and could point to an estimated 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil and more than 320 trillion cubic feet of natural gas off US shores.

Those statements have galvanised a broad opposition, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, Oceana, Ocean Conservation Research, Greenpeace USA, Surfrider Foundation and Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations.

“If it’s the whales now, it’s the fish next. We are literally killing the ocean just by exploring for oil,” said Noah Oppenheim, the fishing group’s executive director. “This is really 99.9 percent of ocean stakeholders versus the 0.1 percent, the oil industry. — Los Angeles Times/TNS

.