Did the chicken you just buy at the supermarket have a nice life, roam free, and eat healthy grains? If you’re the kind of person who cares, Carrefour, the big France-based grocery chain, has the bird for you. Every chicken it sells under its house brand comes complete with its very own life story, thanks to the wonders of blockchain software. All you need to do is scan the label with your smartphone to get all the details.

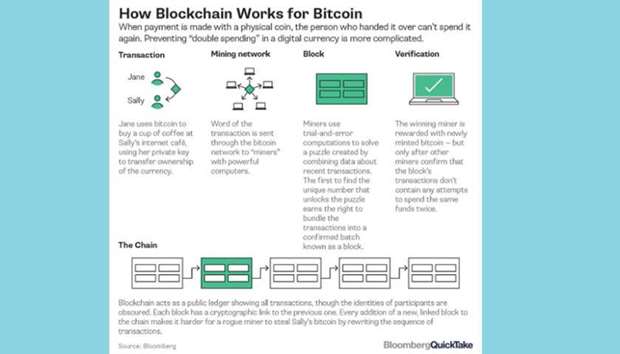

This is the same technology that serves as the backbone of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. The grocery giant isn’t just trying to appeal to discriminating foodies. It wants to do whatever it can to ensure its products aren’t tainted, part of a broader industry trend that buys into the as-yet-unproven promise that blockchain can improve food safety.

Nestlé, Dole Food, Unilever, and Tyson Foods are working with their biggest customer, Walmart. Kroger and JD.com, China’s second-largest e-commerce operator, have also joined the same blockchain platform built by International Business Machines Corp. Carrefour developed its own system in-house.

“There’s no question about it, blockchain will do for food traceability what the Internet did for communication,” says Frank Yiannas, Walmart Inc’s vice president for food safety and health.

Yiannas cites estimates that for every 1% reduction in food-borne diseases in the US, the economy would benefit by about $700mn from increased productivity, thanks to reduced illness and fewer days lost at work.

Not everyone is so enthusiastic. Critics say blockchain can be a valuable piece of the food-safety puzzle but caution that it can easily be gamed. The online ledger requires manual entries, leaving it prone to human errors or intentional manipulation that could compromise the data chain, says Mitchell Weinberg, chief executive officer of New York-based Inscatech Corp, which investigates food sourcing for evidence of fraud. Messing with the digital ledger, he points out, doesn’t take a tech genius.

“Wouldn’t criminals know how to cheat the blockchain?” Weinberg says. “How would it help with anything fluid or ground-up or chemical in nature? Those can be easily adulterated, and blockchain will never know how, when, or by whom.”

That’s what happened in China in 2008 when melamine, a white crystalline compound used in plastics production, was added to water-diluted milk to increase its protein content. At least six infants died and almost 300,000 fell ill after consuming the altered milk, prompting a massive product recall.

By making suppliers more accountable, proponents say adoption of the technology would help reduce some of the headline-grabbing food tampering of recent years: wood pulp blended with Parmesan cheese; horse meat passed off as minced beef, and plastic mixed in frozen chicken nuggets. Such meddling, health dangers aside, costs the food industry as much as $49bn a year, according to the Washington-based Grocery Manufacturers Association, which estimates a tenth of the food purchased in the US is adulterated.

Reducing waste is another goal. Recalls contribute to the 133bn pounds of food the US Department of Agriculture estimates is lost in the country every year. That accounts for as much as 40% of the nation’s food supply, the USDA says.

So, let’s say there’s a norovirus or listeria outbreak associated with spinach at your local grocer. The current system may require recalling vast amounts of spinach from around the country, because it’s so difficult to identify the origin of contaminated food. With blockchain, grocers can quickly pinpoint the source, narrowed to a single region or even a single farm.

Once in stores, blockchain data — combined with sensors and computer models — could help grocers better gauge the shelf life of produce, according to Donna Dillenberger, an IBM research fellow. Historical information, collected from temperature sensors on the shelf, could be run through predictive models to determine the optimal temperature for, say, strawberries.

Blockchain is making its way to sea, as well. The World Wildlife Fund is testing a combination of radio-frequency identification sensors and blockchain software to track the transport of a tuna on its way from fishing boat to processing plant, according to Bubba Cook, the western and central Pacific tuna programme manager. The idea is to discourage the introduction of illegally caught fish to the food supply.

It won’t be a foolproof system, says Cook, but “blockchain offers a platform that makes illegal or unethical practices infinitely more discoverable than the currently diffuse and opaque supply chains.”

.