The import duty on melting-grade nickel cathode was doubled from 1% to 2%, while that on nickel sulphate was cut from 5.5% to 2%.

Why the differentiation? The reason is that nickel sulphate is a form of the metal highly suited to the production of precursor battery materials.

China, already a leader in the electric vehicle (EV) battery sector, is evidently laying the ground for stimulating imports of nickel in the most readily usable composition for lithium-ion battery processing.

Batteries are still a relatively small part of nickel’s usage profile, representing about 4% of global demand, according to the International Nickel Study Group.

But everyone knows that ratio is only going to increase as the electric vehicle revolution builds momentum.

As it does, however, it could fragment an already cracked market, both in terms of the supply chain and pricing.

Most of the world’s nickel production — about 70% of it — is used as an alloying input in the production of stainless steel.

The type of nickel used for stainless production was historically, in ascending order of price, stainless steel scrap, ferronickel and refined metal.

But the Chinese initiated a materials revolution around the middle of the past decade in response to nickel’s extraordinary bull run to more than $50,000 a tonne in 2007.

Looking for cheaper alternatives, they unearthed a technology that had been explored but never developed, namely nickel pig iron (NPI).

An explosion in this form of the metal has generated far-reaching consequences, including a whole new nickel ore supply stream from Indonesia and the Philippines, the offshoring of NPI production and even stainless steel production to Indonesia and the crash in the nickel price to less than $10,000 in 2016.

Producers of more conventional types of nickel are still struggling to adjust.

Witness the decision late last year by Vale, the world’s largest producer, to mothball production capacity.

Nickel’s existing dynamics, beholden as they are to the needs of stainless steel producers, are highly problematic for the EV sector. Most of the world’s current production growth is taking place in the NPI segment of the market.

NPI production is forecast to hit 700,000 tonnes this year, compared with global refined output of 2.08mn tonnes in 2017, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Global mine output, the research house says, will increase by more than 10% this year but just about all of that will come from Indonesia and the Philippines in the form of nickel ore destined for NPI processing.

The problem is that none of this material is suited for production of the nickel sulphate powder desired by battery makers. It’s not impossible to transform NPI into sulphate, but it’s neither economical nor logical. As a result, to quote Wood Mackenzie, “about half of global nickel production is not available” for battery usage.

The incentive to build new capacity to produce the right sort of nickel, however, is simply not there because of the price impact of the NPI boom. The London Metal Exchange (LME) nickel price is today trading around the $13,000. That’s an improvement on the sub-$10,000 pricing that persisted over the course of 2016 and the first half of 2017.

But, as Vale has shown, it’s still the sort of pricing landscape in which established producers are as likely to shutter existing production capacity as to bring on new operations.

This is a major potential headache for the ever-growing EV segment of the nickel market. In fact, it is a double problem for battery makers because low nickel prices have also served as a deterrent to new cobalt production, another key lithium-ion battery input. Outside of the African copper belt, cobalt tends to be found as a by-product in nickel deposits.

Many smaller miners of such deposits closed during the market downturn of 2015 and 2016 and the nickel price hasn’t moved enough to revitalise any of them.

Future demand for nickel sulphate is only going to accentuate the existing structural tensions between different types and chemistries of nickel.

That’s the nature of the stuff. It comes in so many different varieties that the tradeable commodity is constantly shape-shifting. Take the London Metal Exchange (LME) contract, for example.

Although the exchange’s physical delivery criteria are uniform in terms of minimum purity and impurity levels, they allow for a wide variety of shapes, ranging from pellet to briquettes to cut cathode.

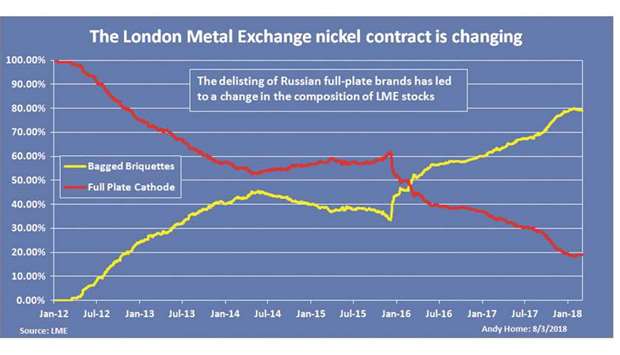

The LME’s decision to delist two Russian brands of full-plate nickel, for the quite understandable reason that Nornickel no longer produces them, has changed the essence of the contract.

Russian full-plate, which used to account for just about all LME stocks, has been shipped to China, where it is still deliverable against the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE). Full-plate nickel currently accounts for less than 20% of total registered stocks.

Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.