Global production of crude steel rose by 5.3% last year, according to the World Steel Association (WSA). As remarkable as the pace of growth was the geographical spread.

Only two of the world’s top 20 steel-producing countries saw output contract last year. The decline registered by Japan, the world’s second-largest producer, was a statistically marginal 0.1%, while the 6.4% drop in Ukraine’s output is only an estimate from the WSA, pending harder figures from the country.

Output everywhere else was up year-on-year, led by stellar increases of 13.1% in Turkey, the world’s eighth-largest producer, and of 9.9% in Brazil, the ninth largest.

Climbing output is being complemented by rising earnings. ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steel producer, has reported a rise in its core 2017 profit of more than a third and a resumption of dividend payments after a two-year gap.

“Market conditions are favourable,” the company said, adding that “the demand environment remains positive...and steel spreads remain healthy.”

This collective steel sweet spot mirrors that in the global manufacturing economy, with purchasing managers indices running strong and analysts expecting more of the same for 2018.

It is also, however, a result of a sharp fall in exports from China, the world’s largest producer. How long such export restraint lasts is the “known known” threat for the rest of the world’s steel industry.

The “known unknown” threat is sitting on US President Donald Trump’s desk in the shape of the “Section 232” report on whether imports of steel threaten the United States’ national security.

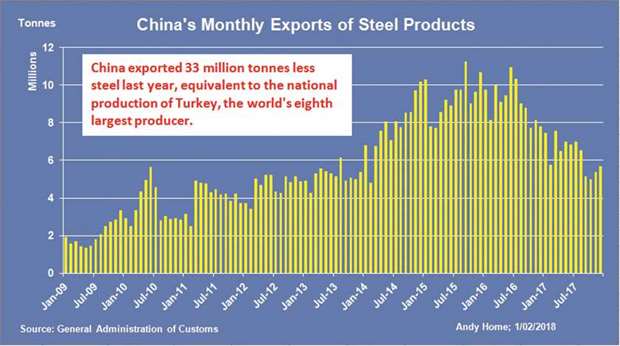

China’s outbound shipments of steel products fell to 75.4mn tonnes last year from 108.5mn in 2016.

The year-on-year difference is equivalent to the national production of Turkey.

It’s this sharp drop in export volumes that has accentuated the positive effects of global manufacturing growth for steel makers such as ArcelorMittal.

The step-change in China’s export profile might seem surprising given WSA figures show the country produced 5.7% more steel last year and lifted its share of world output to 49.2% in 2017 from 49.0% in 2016. The headline count, however, may flatter to deceive.

Not only are the official figures subject to major historical revisions, but they are only the “official” figures. China has forced the closure of a swathe of smaller steel induction furnaces over the last two years.

Most of them were non-permissioned “illegal” operators and as such their collective production, while significant, was never included in the country’s output figures.

Statistically speaking, we don’t know how much China ever really produced, only what its official sector produced.

That official sector is now booming as it plugs gaps in the supply chain resulting from the removal of illegal production.

True, there was a noticeable slowdown in run-rates in the tail end of 2017 as the winter heating restrictions on heavy industry around Beijing kicked in mid-November.

Annualised production slid from 874mn tonnes in September to 789mn tonnes in December. The year-on-year growth rate was just 1.8% in that month.

Beijing’s war on smog injects a whole new level of uncertainty into China’s shifting steel dynamics, disrupting both production and consumption norms.

But the key takeaways are that steel output has been undeniably strong, although just how strong is still open to statistical debate, and steel exports have still dropped.

Why? Because China’s own demand has been so robust. Mirroring the situation in the rest of the world, Chinese steel producers have been enjoying their own sweet spot.

The closure of massive amounts of capacity, both official and unofficial, has coincided with resurgent demand.

The steel sector has been riding the latest construction and infrastructure boom unleashed by Beijing at the start of 2016 to revitalise a flagging economic growth rate.

The promised switch from the old grey industrial growth path to something shinier and more consumerist has been quietly deferred until a future date.

The scale and duration of the 2016 stimulus has surprised just about everyone.

Most metals analysts would have cited Chinese construction-fatigue as their key downside price risk for 2017 but it never came to pass.

Indeed, with stocks of steel products low and the spring construction season looming, it may be deferred a bit longer. But the underlying fade is there to see in the slowdown in real estate investment growth.

It was just 3.1% in December, compared with 7.1% in January. A cooling in such a key driver of China’s steel sector will sooner or later have consequences for either production or exports or quite possibly both. It is, however, expected.

Far less predictable is how the US President will respond to the findings of the “Section 232” report on the country’s steel import dependency.

*Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.