Mark Twain was ahead of his time — so much so that 140 years ago, he had a man cave. On the third floor of the house where he lived when he wrote Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Twain smoked and played billiards with his friends.

These days, smoking is not allowed, but it’s been otherwise restored to perfection, complete with pool table and windows bearing the crests Twain designed — crossed pool cues and pipes surrounded by vessels.

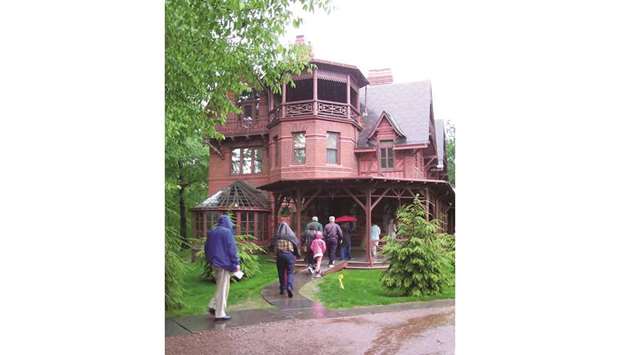

Twain’s house in Hartford, Connecticut, looks just as it might have when he called it home from 1874 to ’91 — albeit with a parking lot, gallery and gift shop.

Some people on a family vacation will go to a cultural institution for a little variety. Me, I decided to visit three nearby writers’ houses — Twain’s, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s and Noah Webster’s — in a single day.

Twain’s is the biggest draw. He’s got an enduring literary legacy, to be sure, but the house itself is pretty fabulous, once named one of the 10 best historic homes in the world by National Geographic.

Decorated by a group of designers led by the not-yet-famous Louis Comfort Tiffany, the house is a splendid, vivid display unto itself. Inspired by the styles of Morocco, India, Japan, China and Turkey, without being particularly faithful to any of them, the decor celebrates intricate design and detail. The front entry hall has breathtaking, Moroccan-ish designs — but painted, rather than inlaid — on the walls, staircase and ceiling.

And each room is different from the last. The tour passed from the salmon-toned parlour to the maroon-and-gold dining room to the blue library, the glass-walled conservatory, the guest room with wallpaper of spiders and bees and up to the second floor. The master bedroom holds the elaborate bed Twain, or rather Samuel Clemens, shared with his wife, Olivia (Livy). They picked up the angel-heavy headboard while living and traveling in Europe for $4,700 in 2017 dollars. The pillows are propped at the bottom of the bed, backward, which is how Sam and Livy slept, because, as Twain quipped, he wanted to see what he had paid for.

That anecdote got a laugh on my tour. Twain’s quick wit and his live performances — which was how he made money when he lost a fortune in bad investments — make him basically a Victorian star stand-up comic. He nurtured fame, creating a persona that connects with people today, perhaps even more so than his books.

It’s Twain/Clemens as a person who is emphasised as you walk through the halls where he once did, and apart from the madcap design, I think that’s what keeps people coming back to his house — imagining joining him at this very dining room table or sitting in the library as he stands by the mantle, spinning tales.

It’s quite different for Harriet Beecher Stowe, who didn’t exude fun. Born in 1811 in Connecticut, she was from a family of clergymen so well known that she kept “Beecher” when she published for the name recognition. She eventually eclipsed them all, becoming a mega-bestselling author. That was why Twain, when he was still an aspiring novelist, built his house adjacent to hers — to rub literary shoulders. From his house, I walked in the rain across a plaza to the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

While it is also a house museum, the Stowe Center is focused on engaging its visitors in talking about social change. On my tour, we discussed the details of the home’s recent gorgeous restoration alongside the news of the day — immigrants being deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement — and how that related to Stowe’s most famous work, which was sparked by her anger over the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

That book, of course, is Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which tells the story of a slave who is denied his freedom. Published in serial form in the abolitionist newspaper the National Era in 1851, the story was initially going to span three to four episodes, but its popularity pushed it to more than 40 — with a cliffhanger ending, which could be found only in the two-volume book released in 1852. It was a brilliant move — Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold 10,000 copies in the United States in its first week and 300,000 that year.

These sales were in support of the abolitionist cause, but over time Uncle Tom came to mean something else: a black person who is obsequious toward whites. The Stowe house addresses that change directly, in its visuals and conversations, and in so doing asks us to consider culture in context and the power of having a voice.

Noah Webster is best remembered for the words he put in people’s mouths: He published the American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828, codifying an American language that was distinct from England’s. It was, philosophically, an extension of a project he’d begun in the 1780s, publishing standardised books for American schools called blue-backed spellers.

Webster was born in 1758 at the West Hartford home that now serves as his museum. The two-story colonial farmhouse has the broad floorboards of old trees and fireplaces five feet wide. Much of the docent-led tour focused on what it took to spin wool, cook food and keep warm in 18th-century Connecticut.

Webster’s father mortgaged his farm to send him to Yale, but Webster was ungrateful and, after he became successful, never returned the favor. Eventually the property fell out of the Webster family hands. In 1909, it was listed for sale; my great-grandfather and great-grandmother bought it.

In the house, Alice and Arnold Hamilton had their second son, Fred, and then a daughter. They installed a heater and added new flooring but by 1913 wanted a more modern home for their family, which they built nearby. The Webster house remained unoccupied until 1937 when their daughter and her new husband decided it would be a nice — and, I imagine, free — place to start their life together.

Inspired, her brother Fred decided he wanted the Webster house two years later and moved in with his new wife, Jane. They lived there for 20 years, raising their three children and modernising along the way. In general, their improvements were gradual; underneath their changes the original fireplaces and woodwork remained.

“We have often been asked to describe living in the house where one of our country’s greatest educators and the father of our universal American language lived,” Fred later wrote. “Our answers were very practical. It was too hot in the summer and much too cold in the winter … . On the other hand, when we entertained, the house exuded a feeling of closeness and warmth.”

Outside, a plaque and stone marker declared the home to be Webster’s birthplace, and in the 1950s the curious would stop and knock on the door. “We would try to accommodate such visitors, saying in an unusually loud voice, ‘It is not a museum, but we’d be delighted to show it,’” Fred wrote. “This was a signal for our children to shove all their misplaced clothes and junk under their beds.”

In 1960, Fred did as his parents had and moved his family into another house nearby. In 1962, the Hamilton family donated the house to the town of West Hartford; it was restored and opened as a museum in the mid-1960s. It is now run by the Noah Webster Foundation and the West Hartford Historical Society.

I never met my great-grandfather, and as I knew her, my great-grandmother was eerie, intimidating and impossibly old. The photo of them, above left, was taken around the time they bought the Webster house. They are wearing matching shoes. A pigeon seems to have crashed head-first into her hat. They look like they are cracking each other up, and Arnold looks just like his son, Fred.

Imagine them buying the house more than 100 years ago: It was just an isolated place on the edge of town with a bit of literary colonial history. Writers’ houses like these are so often torn down, reconfigured, forgotten. That these three have survived tells us something about ourselves now: We love wit, that the stories we tell empower social change, and we are defined by sharing language. We Americans are not very good at remembering our cultural history — but sometimes it’s the place we call home. — Los Angeles Times/TNS

FOOTPRINTS: The Mark Twain House set in a leafy neighbourhood of Hartford, Connecticut, was home to famed American author, his wife and three daughters from 1874-1891; right, the famous author relaxing at home.