US-Pakistan

relations hit a new low in 2017 and a series of high-level contacts

between the two countries exposed the weakness in this relationship

instead of strengthening it.

It was also during 2017 that the US

administration announced a new strategy for winning the war in

Afghanistan, urging Pakistan to join the US-led efforts to defeat the

Taliban in the battlefield.

The policy recognises Pakistan’s right to reject the US offer but warns that there will be consequences if it decides to do so.

In

statements, US President Donald Trump, his vice-president Mike Pence,

secretaries of defence and state, and national security advisers and

other senior officials highlighted the consequences that the policy

hints at, from stopping US economic and military assistance to raising

doubts about Pakistan’s ability to provide “responsible stewardship” to

its nuclear assets.

Some officials warned that Pakistan could “lose territory” if it did not eradicate terrorist safe havens from its soil.

Others said the US could take “unilateral action” in areas of divergence with Pakistan.

The

statements, along with the pronouncement that India now is the

strongest US ally, alarmed Pakistan, forcing it to look for other

options to protect its interests.

Initially, Pakistan reacted

cautiously to these threats, but on Thursday, military spokesman Major

General Asif Ghafoor told the United States and Afghanistan that it is

time for them to do more for Pakistan, instead of asking Islamabad to do

so.

“No organised infrastructure of any banned organisation is

present in Pakistan. We have fought an imposed and imported war twice in

Pakistan and now we cannot do any more for anyone,” he said.

But the

same day, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson offered to partner with

Pakistan against terrorism, indicating that the Trump administration

still hopes to persuade Islamabad to accept its demands despite the

recent bitterness.

The Pakistani establishment’s strong reaction to

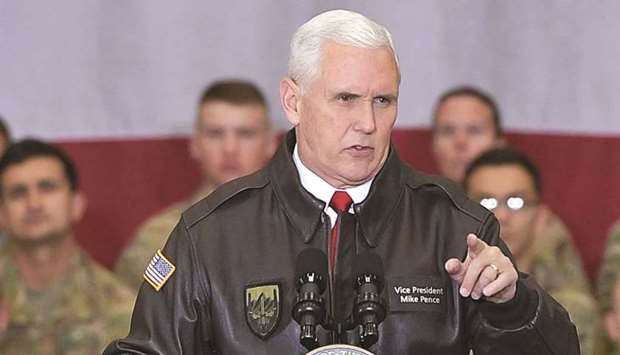

these demands followed a warning from Vice-President Pence that

President “Trump has put Pakistan on notice”, and that “Pakistan has

much to gain from partnering with the United States, and much to lose by

continuing to harbour criminals and terrorists”.

The warnings and high-level visits to Pakistan started in August.

In

the last four months, half a dozen US officials have visited Islamabad

to persuade Pakistan to support the new US policy, including Secretary

of State Rex Tillerson, Secretary of Defence James Mattis, Centcom chief

General Joseph Votel, and Trump South Asia adviser Lisa Curtis and

Assistant Secretary of State Alice G Wells.

The visitors met key

Pakistani leaders including Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, Army

Chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa, and ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence)

chief Lieutenant General Naveed Mukhtar.

However, the only positive

comment that came out of such contacts was the expression of a desire to

continue working for “a common ground”.

Tillerson said after his

October visit that he told Pakistani leadership that Washington would

implement its new strategy with or without their support.

“And if you

don’t want to do that, don’t feel you can do it, we’ll adjust our

tactics and our strategies to achieve the same objective a different

way,” he said.

The next visitor was Mattis who repeated a US call on

the Pakistan government to “do more” after a meeting with Pakistani

leaders early this month.

This lack of progress in these contacts

shows differences between Islamabad and Washington over the new US

strategy which claims that Pakistan “often gives safe haven to agents of

chaos, violence, and terror”.

While announcing the new strategy,

Trump also said that the US has been “paying Pakistan billions and

billions of dollars at the same time they are housing the very

terrorists that we are fighting” but this must stop now.

Pakistan

says that US leaders continue to repeat a false claim – that Islamabad

shelters terrorists – and reminds them that friends “do not put each

other on notice”.

Michael Kugelman, deputy director for South Asia at

the US-based Wilson Centre, says he does not believe such threats could

change Pakistan’s response to the US demand in the near future.

“From a Pakistani perspective, it makes perfect sense to have the Afghan Taliban in their corner,” said Kugelman.

“Pakistan,

just like everyone else in the region, assumes that eventually, US

troops will withdraw from Afghanistan,” he told Al Jazeera.

When that

withdrawal happens, Kugelman added, there was a risk of “rampant

destabilisation and civil war in Afghanistan”, and a relationship with

the Afghan Taliban would be valuable for Pakistan in that context.

During a surprise visit to Afghanistan earlier this month, US Vice-President Pence said that the Trump administration had ‘put Pakistan on notice’.