Wall Street’s robot revolution has begun. JPMorgan Chase & Co is rolling out a programme called LOXM that executes equities trades so well, it’s replacing the humans who used to do that. Goldman Sachs is in the midst of automating the initial public offering process. Innovations in financial technology – fintech – are creating competition in fields long dominated by the institutions. Vikram Pandit, who ran Citigroup Inc during the financial crisis, says technological advances could make 30% of banking jobs disappear in five years. David Siegel, co-founder of quant hedge fund Two Sigma, is worried that machines will soon make swaths of the workforce obsolete. But all hope is not lost.

What makes robots qualified for Wall St work?

Artificial intelligence, a branch of computer science, which aims to imbue machines with aspects of reasoning. Today, the term includes machine learning, which is the ability for computers to learn by ingesting data, and natural language processing – the ability to read or produce text. Robotic process automation is a more simple form of AI that performs rote tasks like answering administrative requests.

Who is most at danger of losing their job to a robot?

The first to go will be those with roles that are repetitive in nature: support functions, back-office processing, producing reports that rely on structured data. (At JPMorgan, bots will handle 1.7mn requests this year, doing the work of 140 people, for tasks such as resetting employees’ passwords). Accountants who “spend a lot of the time basically being an abacus” were singled out by Deutsche Bank chief executive officer John Cryan as being at risk of losing their jobs. McKinsey & Co partner Jared Moon predicts that technologies sweeping through investment banks will relieve rank-and-file employees of about a third of their current workload.

How many jobs could be affected?

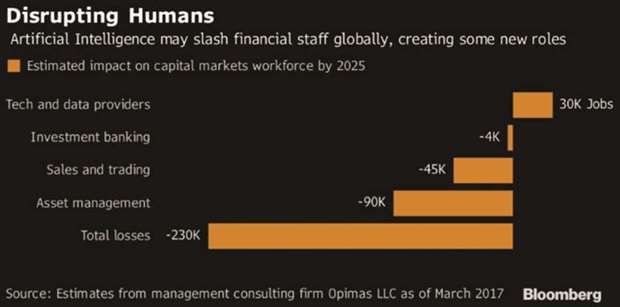

Management consultant Opimas predicts 90,000 people in asset management (or 30% of those workers) will be replaced by machines by 2025, along with 45,000 jobs in sales and trading, which would amount to a 15% reduction. The overall reduction in headcount will be about 230,000 people, or 18%, Opimas says. About four of every five Wall Street firms have already implemented, or plan to use, some form of AI, according to Greenwich Associates.

Who else should be worried?

Consider the junior investment banker, who spends much of his or her time collecting and analysing data and then creating reports. Consulting firm Kognetics found that investment-banking analysts spend upwards of 16 hours in the office a day, and almost half of that is spent on tasks like modelling and updating charts for pitch books. Machine learning, and natural language processing techniques, are already very good at this. Workers in compliance and regulation have a different worry: Over the last five years, their ranks have doubled, while overall headcount at banks declined 10%, according to research by Citigroup. Automating those activities – so-called regtech – could be good news for financial institutions looking to control the rising cost of compliance, and bad news for people looking to keep their jobs.

What jobs are most threatened by fintech?

Startups including LendingClub Corp and On Deck Capital Inc pioneered online lending, quickly matching consumers looking to borrow with people looking to make a profit on interest. Now, banks are looking to compete, announcing their own online loan portals and inking partnerships with fintech companies. That makes loan officers and clerks among the professions most vulnerable to automation, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Is there good news for anybody?

Opimas says as many as 27,000 new jobs will be created for technology and data workers. New jobs like machine-learning engineers and data scientists are increasingly in demand. American banks are investing more in AI than European or Asian banks, so they will potentially see market share gains in capital markets businesses, according to Moon.

What’s the strongest case for keeping humans at the wheel?

It’s still hard to automate empathy or trust, so as long as buyside clients want to phone up a salesperson, people will have jobs. And in cases when institutional buyers want to make a large block trade, or are particularly interested in discretion, they will still want to call on human traders. Still, electronic platforms are continually taking over volumes in more asset classes, and clients are requesting algorithms rather than people because e-trading tends to be faster and cheaper. One example: Algorithms have replaced many equity sales traders.

How should those starting out in finance prepare?

“Be tech-savvy, be client-savvy or be data-savvy,” says Richard Johnson of Greenwich Associates. In other words, learn to work with the tech as banks deploy it across their business. Or focus on relationship management, which probably can’t be done by computers. (Without customers, after all, banks have no business.) Or focus on data science, helping banks analyse and interpret the information that AI depends on. McKinsey’s Moon is a bit more blunt: “Learn to code in Python.” That’s the programming language used by investment banks including JPMorgan and Bank of America Corp.