He’s a wanderer too. Not to mention a relentless documenter — of international human rights violations, of the 40-some cats that roam his Beijing art studio and of the longtime team members who populate his Berlin art studio, a 150-year-old underground beer cellar.

Tonight it’s the moon that has captured Ai’s attention.

He arrived a few hours ago at LAX and now strolls languidly across his agent’s Beverly Hills office courtyard, repeatedly stopping to take photos of the sky.

”Beautiful half moon,” he says, breathing in the floral-scented night air.

He takes pictures of his agent’s lobby and pictures of a framed picture on the lobby wall. Each time, he extends his arm without breaking his stride, briefly eyeballing the viewfinder from afar, an unemotional, matter-of-fact gesture: capture the moment.

In 2016, an accumulation of moments from the better part of a year resulted in his new documentary, Human Flow, a sweeping chronicle of the swelling refugee crisis. Ai and his team crisscrossed the globe, visiting more than 40 refugee camps in 23 countries and banking about 900 hours of footage for the film, which premiered in September at the Venice International Film Festival and screened at the Telluride Film Festival.

In one scene, travel-weary refugees spill out of rubber boats washing ashore on a beach in Lesbos, Greece, in the dark of night; in another, thousands from Syria and Iraq slog along a mud footpath headed toward the Greek-Macedonian border, gravel crunching beneath their feet. In southern Italy, African refugees from Nigeria, Sudan and Senegal huddle under gold Mylar blankets that glisten in the moonlight and crinkle in the breeze.

This is not an abstract art film, as one might expect from the man who filled a vast exhibition space in London’s Tate Modern with 100 million hand-sculpted and painted porcelain sunflower seeds. Nor is it a straightforward, journalistic documentary. It is a tragic travelogue of sorts.

There may be talking heads in Human Flow, such as Jordanian Princess Dana Firas and Syrian astronaut Mohammad Fares, and there are snippets of factoids about the more than 65 million people worldwide escaping war, persecution, climate change and famine. But they unfold over lush, ambitious visuals shot with a variety of cameras including drones and even Ai’s iPhone. The film is studded with the kind of iconic imagery present in much of his contemporary art — mounds of battered life vests, thermal blankets, fragile rubber boats.

“It’s incredibly beautiful and aesthetically complex and layered and textured,” says Participant Media’s Diane Weyermann, an executive producer on the film. “He didn’t set out to make an art film; he set out to make a film about humanity. It’s a story about the global refugee crisis made by an artist.”

“I want people to be emotionally involved,” Ai says over dinner, “to realise these refugees relate to our normal life and we have a responsibility to act.”

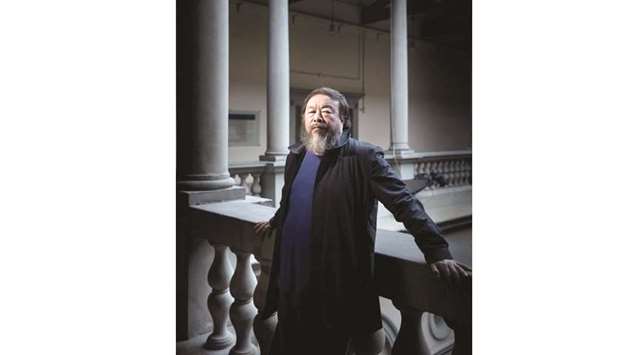

As he speaks, Ai is a mix of contradictions: gentle, soft-spoken and cherubic-faced with a Zen-like air of calm but also a brazen human rights activist with a quick sense of humour who is not immune to the allures of posting blow-by-blow accounts of his day over social media. But instead of avocado toast, his feed might include pictures of Al Gore, Julian Assange or Chelsea Manning. He oozes sensitivity and machismo at once.

“I try to keep intimate relations with what we call our life,” Ai says of his ceaseless documenting, “because very often we don’t understand our life. We think we are living inside our (lives), but we don’t really understand.”

‘Starting from zero’

As a multimedia political provocateur, Ai’s studio has made some 20 films, both shorts and long form, largely championing human rights and freedom of expression. Many have been DIY efforts and most have been distributed on Ai’s YouTube channel. The online activism landed him in hot water with the Chinese government, which in 2011 accused him of vague economic crimes, confiscated his passport and jailed him. They called his Internet activities subversion of state power and he was held for 81 days, much of that time in solitary confinement. When his passport was returned in 2015, Ai moved to Berlin, where he now lives.

By then he’d been studying the plight of refugees for some time. But he wanted to go deeper. He traveled to a beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, the well-known way station for refugees, and began filming the tiny boats arriving from Turkey with his iPhone. The scene was so active and the images so strong, he set up a small studio there. He didn’t plan to make a feature-length film. It came from his pressing curiosity to better understand the refugees’ journeys.

“I was starting from zero,” he says. “Even before I could freely travel … I started to read all the news, books. We did research about the history of the human flow. It was a learning process.”

Ai’s passion for the plight of refugees comes from a profoundly personal place. He not only understands government persecution, but he grew up as a displaced person himself. His father, Ai Qing, was a revered poet who during the Cultural Revolution was persecuted by the government. The family was exiled to a remote Gobi desert village, Xinjiang, where they lived in harsh conditions. As a result, the artist felt strangely familiar, even comfortable, in the refugee camps he visited during filming.

“I had all those experiences of people being discriminated (against) or punished for the wrong reasons,” he says of his youth. “For me, it’s very natural. I can easily, when I’m facing (the refugees), see in their eyes how they are trying to survive. I understand them very well.”

If he had one agenda with Human Flow, it was to humanise refugees, showing their universal struggle for basic needs like food, shelter and safety. Toward that end, he presents the benign rhythms of their lives — a little girl playing hopscotch in one camp, Iraqi women smoothing flatbread dough on cooking stones in another. He also threads the film with candid shots of refugees just before their one-on-one interviews begin. They settle into their seats and face the camera, fidgeting, giggling nervously or simply staring off.

Ai also appears throughout the film, sometimes with his iPhone, but also quietly interacting with his subjects, offering them food or emotional reassurances or simply letting one man cut his hair.

“To get yourself involved, to (make) the situation a little bit lighter, make some jokes, do some funny things like cut hair or barbecue … it brings a human touch,” he says. “It’s everyday life. It’s humanising them. And humanising myself. I don’t want just to be there as a filmmaker. I want also to tell them that I know them so well. I know exactly what kind of conditions they are in.”

Moral high ground

Human Flow ends at the US-Mexico border, a not-so-subtle nod to President Trump’s stance on immigration. “It’s very hard to face this kind of reality (of) what Trump’s doing — to have this traveling ban, and to build this wall, this is really backward, it doesn’t make any sense,” Ai says.

Whether he will continue making commercial films remains up in the air. Ai has eight solo exhibitions in museums and galleries around the world, including the Public Art Fund’s Good Fences Make Good Neighbors in New York, for which he’ll erect more than 300 works across the city’s five boroughs. The large-scale, site-specific installations, documentary photographs, lamppost banners, “public interventions” and other works will use the image of the security fence, exploring how it divides people. And with filmmaker Wang Fen, he co-curated the Guggenheim Museum’s documentary film series, Turn It On: China On Film, 2000 — 2017, which opened Friday.

The Guggenheim festival is part of the museum’s now-controversial exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, for which Ai served as an adviser. Before its opening the Friday before last, the Guggenheim removed three works from the show after threats of violence were made against the museum’s staff after criticism of the treatment of dogs and other animals featured in the pieces. Ai, an animal lover who featured a scene in Human Flow of a tiger released from a Gaza zoo into the South African wild, has been vocal on the incident — but in support of the Guggenheim.

“As an artist or a defender of human rights, I am highly conscious of the respect we should show to other lives and of the need to protect their rights. However, when anyone uses a moral high ground to judge an art exhibition and to demand the withdrawal of contents that may or may not violate those rights, it presents a potential danger of violating the freedom of speech,” he relays in a message after our interview. “A healthy society only exists when any issue can be talked about or exhibited in a way that shows the conditions for and against arguments, so to structure possible discussions.”

All the while, the ongoing refugee crisis weighs on him.

At the LA reception for Ai, after a screening of Human Flow, all eyes are on the artist. But he sits off to the side, watching the caterers, a family of Syrian refugees.

Maaysa Kanjo and her husband, Abdul, make their way through the crowd toward Ai. In a long party dress and traditional headscarf, Maaysa presents him with a framed ink drawing of a blooming rose. They haven’t seen his movie yet, they say, but are eternally grateful it exists.

“To give the people an idea what’s going on there, to show the people,” Maaysa says. “We appreciate it so much. Our story.”

Any solution to the refugee crisis, Ai had said earlier, begins with simply bearing witness to it.

“All these tragedies are man-made. If we can cause the tragedy, we can solve the tragedy if we are willing to,” he said. “To find the humanity. This is the only thing we can hope.” — Los Angeles Times/TNS

MAN OF MANY PARTS: Ai Wewei is gentle, soft-spoken and cherubic-faced with a Zen-like air of calm but also a brazen human rights activist with a quick sense of humour who is not immune to the allures of posting blow-by-blow accounts of his day over social media.