An

estimated 20,000 indigenous children taken from their families starting

in the 1960s and placed for adoption or fostering will share in a

C$800mn ($640mn) payout, the government announced yesterday.

The

so-called “Sixties Scoop” saw them placed with primarily white

middle-class families in Canada, the United States and overseas.

In

recent years, as the children grew into adults and became aware of their

past, several lawsuits and class actions have been filed over their

loss of aboriginal identity, claiming in court documents that it

resulted in psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, unemployment,

violence, and suicides.

“People affected by the Sixties Scoop have

told us that the loss of their culture and language are among the worst

kinds of harm that they suffered,” Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn

Bennett told a press conference. “That is why our government is

responding directly to remedy the ill-advised (policies) of the past.”

A

visibly moved Bennett introduced six Scoop survivors: four who were

raised in the United States, another who now speaks with a Scottish

accent, and a sixth who had been taken from her home in the Arctic and

placed with a family in Nova Scotia province, more than 6,000km (3,725

miles) away.

“Their stories are heartbreaking,” Bennett said,

describing firsthand accounts of their “identity being stolen” and

“about not really feeling that you belong anywhere”.

“I have great

hope,” said lead plaintiff and Beaverhouse First Nations chief Marcia

Brown Martel, “that this will never, ever happen in Canada again.”

The

Sixties Scoop, which actually continued into the 1980s, is just the

latest historical wrong suffered by Canada’s indigenous peoples that

Ottawa has sought to redress.

Starting in 1874, 150,000 Indian,

Inuit, and Metis children in Canada were forcibly enrolled in 139

boarding schools run by Christian churches – including the Catholic

church – on behalf of the federal government in an effort to integrate

them into society.

Many survivors alleged abuse by headmasters and teachers, who stripped them of their culture and language.

At least 3,200 students never returned home.

The experience has been blamed for gross poverty and desperation in native communities that bred abuse, suicide and crime.

Ottawa formally apologised in 2008 for the “cultural genocide” as part of a C$1.9bn ($1.5bn) settlement with former students.

The

government also launched an inquiry last year into the

disproportionately high rate of killings and disappearances of

indigenous women and girls in Canada.

Indigenous women represent 4% of Canada’s population but 16% of homicide victims.

More than 1,200 were murdered or have gone missing over the past three decades.

Bennett was at a loss to explain Canada’s past assimilation policies.

“I

don’t know what people were thinking,” said the former paediatrician.

“I don’t know how governments thought they could do a better job (at

raising children) than their parents, their village, their community.”

Bennett said an official apology would be forthcoming.

She also said there may still be a need to “totally overhaul the child welfare system as it is right now”.

“Too many children are still being taken from their families,” the minister said.

The

settlement, which still requires court approval, will be split between

Scoop survivors and a reconciliation foundation that will help them to

reacquire their language and culture, with C$750mn going directly to the

survivors.

A small number of lawsuits launched by other survivors

remain outstanding and are not included in the settlement, but Bennett

said she would “work with them” toward a resolution.

Those individuals who were sent abroad to live with foreign families will also be invited to return to Canada, if they wish.

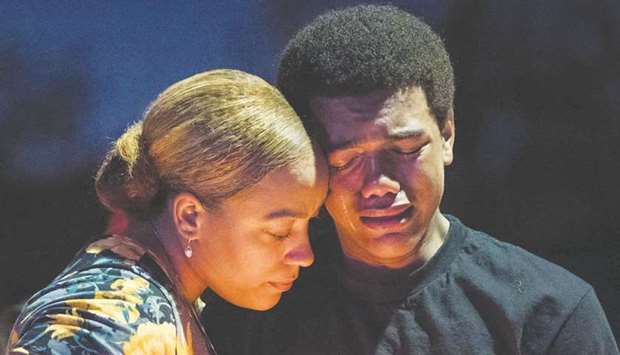

Veronica Hartfield, the widow of slain Las Vegas officer Charleston Hartfield, and their son Ayzayah, 15, are seen at the vigil for Hartfield.