China, which signed up to the US-drafted resolution, will lose an increasingly significant flow of raw materials to its lead smelters.

The news has reinvigorated a market that had lost its bull narrative thread.

London Metal Exchange (LME) lead for three-months delivery hit a nine-month high of $2,537 per tonne on Thursday morning.

Not as exciting as zinc, which has just surged to its highest level in over a decade. But being overshadowed by its more glamorous sister metal is nothing new for lead.

Characterised by a lack of statistical clarity and only sporadic news flow, lead tends to get regularly punished on the London market in the form of the popular relative value trade against zinc.

The sanctions news, however, has refocused attention on the state of China’s lead market. But is it tight or is it sufficiently well supplied to absorb the loss of North Korean material?

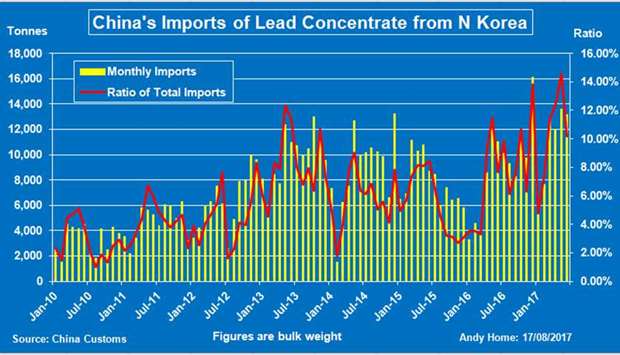

China imported 108,000 tonnes of lead concentrates from North Korea least year, making its neighbour the fourth largest supplier after the United States, Russia and Peru.

Imports in the first half of this year totalled 64,000 tonnes, making North Korea the second-largest supplier after Russia.

These figures, it should be emphasised, denote bulk tonnage, not metal contained.

Judging by the implied value of North Korean imports, this seems to be relatively low-grade material, meaning lower metal content.

The average implied price for North Korean imports in June was $800 per tonne, compared with $1,965 for Peruvian material.

But North Korea is accounting for an ever-rising ratio of China’s total lead concentrate imports because the total figure has been trending steadily lower since the middle of 2015.

A tightening raw materials market mirrors zinc’s bull narrative for the very good reason that the two metals tend to be mined from the same deposits.

The zinc mine closures that have inflamed that metal’s bull spirits have also taken their toll on lead production.

The International Lead and Zinc Group (ILZSG) estimates that mined production outside of China fell in both 2015 and 2016, albeit with a mild recovery in the first part of this year. However, it’s what’s happening in China that divides opinions on the two metals’ relative price outlook.

Earlier last week China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported that the country’s refined zinc production fell by 6% in June, providing yet another fillip for zinc’s bull run.

The numbers for lead, however, were if anything bearish, with national production rising by 6%. The ILZSG estimates refined production in China rose by 13% in the first five months of this year, while mined production jumped by 23% to 1.14mn tonnes from 928,000 tonnes.

If these numbers are right, there’s nothing to see here for lead bulls.

China would seem well capable of absorbing the loss of North Korean lead concentrates. But are they right?

Chinese statistics on its metals sector can be opaque at the best of times, but when it comes to lead, we’re entering a particularly ill-lit place.

The country is host to a large number of small miners, many of them operating beyond the NBS’ statistical reach, meaning restricted visibility on what’s actually coming out of the ground.

The ILZSG’s different “apparent” calculations, meanwhile, can’t capture any changes in smelter stocks of concentrates.

If China’s lead smelters have drawn stocks to offset falling raw materials availability, the outcome of the ILZSG’s methodology would be a jump in “apparent” production. Production could be up. Or stocks could be down. Or a bit of both. Confusing, isn’t it? Try some different numbers, these ones from Thomson Reuters GFMS.

Analyst Wenyu Yao estimates that China’s mined production has risen by only a marginal 2% so far this year, while “primary lead production in the first seven months has decreased by 6.64% year-on-year in large part due to concentrate supply tightness”. (“Lead’s near-term fundamentals provide upside potential”, August 16, 2017). It’s this sort of statistical hall of mirrors that bedevils analysis of lead’s underlying supply and demand dynamics.

And it’s why this market struggles to generate any coherent narrative.

So is China comfortably supplied with lead or short of the stuff? Two harder bits of statistical evidence would seem to favour the latter interpretation.

The country has started importing refined lead in significant tonnages for the first time since 2009.

Imports totalled 52,500 tonnes in the first half of the year, compared with just 135 tonnes in the same period of 2016.

Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.