But instead, the flow from North Africa has ebbed, with the most recent figures from the Italian Interior Ministry clocking up just under 97,000 arrivals since January 1, a near 4% reduction since the same period of 2016.

The fall in arrivals was registered just after Italy decided to send a naval mission to Libya to help the local coastguard intercept sea migrants, and drafted a code of conduct to rein in Mediterranean Sea rescues by non-governmental groups (NGOs). Yesterday, as it recorded a 57% drop in migrant landings to Italy from June to July, EU border agency Frontex said an “increased presence” of the Italian-backed Libyan coastguard “discouraged the people smugglers from sending out boats with migrants.”

The Italian press has lionised Interior Minister Marco Minniti as the frontman of the tougher line on migration, and talked up the mean-looking former intelligence expert as the ruling Democrats’ best hope against populist opposition parties in next year’s elections.

According to an Ixe poll from last week, 86% of Italians believe their country is experiencing a migration “emergency” and 46% approve of the interior minister’s initiatives. Eighteen per cent would like him to be even tougher.

But the impact of government action in Rome on developments on the ground in Libya is still unclear, while human rights groups and experts have questioned the moral and legal legitimacy of Italy’s moves.

Frontex also cited adverse sea conditions and violence in the major Libyan port city of Sabratah as constraining factors for migrant departures, and noted that arrivals surged in Spain, suggesting that the flow Italy was trying to stop may resurface elsewhere.

Mattia Toaldo, a Libya expert at the European Council of Foreign Relations, added in an interview with DPA that an Italo-Franco-German military mission in Niger could also be credited for closing the Africa-Europe migration route further upstream.

Furthermore, the analyst suggested that migrant trafficking within Libya may have become harder due to internal strife and may be losing out to “equally lucrative, but less visible, trafficking of fuel, or, even worse, of drugs and weapons.”

However, restricting the possibility for people to flee from Libya - a country largely ruled by militias where torture, rape and other abuse against migrants is well documented - has serious human rights implications.

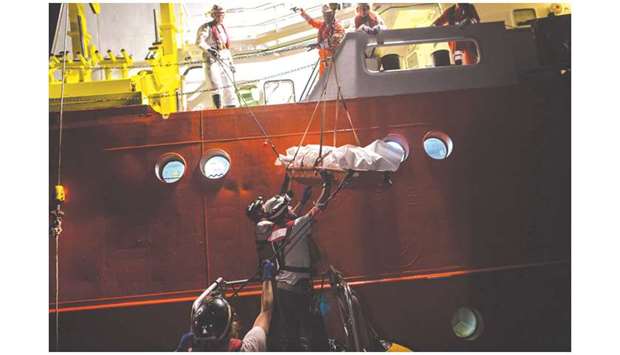

On the weekend, three NGOs, including high-profile outfits such as Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and Save the Children, suspended sea migrant rescue work after being asked by the Libyans to stay clear of a newly-established “search and rescue” zone guarded by Tripoli.

Earlier, MSF and others refused to sign Minniti’s code of conduct, arguing that requirements to accept armed Italian police on their ships to help investigations against smugglers, and a ban on at sea transfers of rescued migrants were unacceptable constraints.

“If humanitarian ships are pushed out of the Mediterranean, there will be fewer ships in the area to rescue people from drowning,” Annemarie Loof, MSF operational manager, said in a Saturday statement.

According to Toaldo, Italy is “subcontracting” to the Libyans the practice of migrant push-backs, which are illegal under international law, and stressed it may risk compromising its long-term goal of stabilising its former colony.

Libya has at least two competing governments.

The Italian mission was requested by UN-backed prime minister Fayez Serraj, but it was seen as a hostile gesture by Khalifa Haftar, a military strongman that controls eastern Libya.

“Sending those ships has provoked quite a backlash against Italian policy in Libya, which had so far been largely well received. I wonder if [it] was worth the trouble of provoking so much opposition,” Toaldo said.

Matteo Villa, a migration expert at Italian think tank ISPI, said it is “too early” to judge whether Italy’s actions will ultimately be successful, as “politics” in Libya can easily reverse the gains made so far.

In a “fact checking” analysis posted on Twitter, Villa concluded:

“Problem is whether we want open-air prison & abuses there. In the end, only stability in #Libya can create more jobs for #migrants, restore circular migration. NGOs are not to blame.”