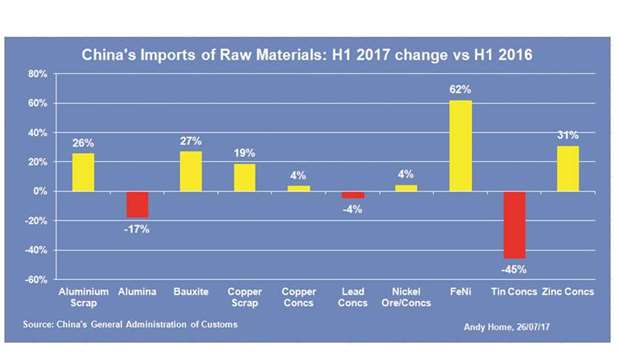

China’s appetite for imports of refined industrial metals was generally subdued in the first half of the year.

Those of copper, for example, fell by 26%, or over 500,000 tonnes, relative to the first half of 2016. In part that was due to strong imports of both copper scrap and mine concentrates.

Ample availability of both raw materials meant higher domestic production of refined copper and less demand for imported metal. A similar pattern played out in both the zinc and nickel sectors despite expectations that a lack of raw materials in each would feed through to higher refined imports.

The stand-out exception was lead, which saw concentrate imports slide and China flip from net exporter to net importer of lead in refined metal form.

China’s net imports of refined lead totalled 50,300 tonnes in the first half of 2017 — which may not sound like a lot of lead but it was the first time China has been a consistent net importer since 2012 and you’d have to go all the way back to 2009 to find it importing equivalent tonnage.

The imports largely came from just two countries, namely Australia (32,000 tonnes) and Kazakhstan (18,600 tonnes).

What has caused the flip from net exporter to net importer? This being lead, a notoriously opaque market even outside of China, it’s a little hard to say.

But it’s noticeable that imports of lead concentrates dropped in the first six months of 2017, also defying the broader trend. At 644,000 tonnes (bulk weight) they were 4% lower year-on-year and, indeed, the lowest quantity for any first half period since 2013.

All of which is somewhat ironic since this is what everyone was expecting to happen to lead’s sister metal zinc.

But zinc concentrate imports were a robust 1.3mn tonnes (also bulk weight), up 31% on the first half of last year despite a tightening raw materials market.

Conversely, imports of refined zinc slid 38%, or 111,000 tonnes, to 180,000 tonnes.

China’s zinc trade so far this year has not conformed to this market’s bull narrative of raw materials crunch translating into refined metal crunch.

Imports of refined copper and refined nickel were both lower in the first half of the year, while imports of raw materials were higher.

In the case of copper, the big change was the pick-up in imports of scrap, which surged by 19% to 1.9mn tonnes (bulk weight). That broke a downtrend that had been running for the last four years and was part and parcel of a global surge in scrap availability occasioned by the sharp jump in the copper price at the end of last year.

Imports of mined copper concentrates, by contrast, have been steadily rising over the past five years and that trend was extended in the first six months of 2017 to the tune of a further four-percent increase.

This reflects a structural shift caused by China’s build-out of smelting and refining capacity, albeit one accelerated by the cyclical abundance of scrap metal.

The impact on refined copper imports was a cumulative 533,000 drop over the January-June period, or a 500,000-tonne drop in net terms due to slightly lower exports. Nickel raw material imports have also boomed this year, reducing net import demand for refined nickel by 61%, or 139,000 tonnes, to 87,500 tonnes.

Flows of nickel ore from the Philippines have been picking up steadily so far this year after being hit by a combination of the rainy season and the clamp-down on nickel mining initiated by former environment secretary Regina Lopez and now suspended by her replacement Roy Cimatu.

Imports of ore from Indonesia have also now resumed in earnest after that country part-reversed a ban on the export of unprocessed minerals.

The ban was intended to coerce miners down the value-add processing chain, a policy which has borne fruit in the form of a new stream of nickel pig iron (NPI) flowing from Indonesia to China.

Confusingly lumped in to the ferronickel category by China’s customs department, imports of Indonesian NPI totalled 563,000 tonnes in the first half of 2017, up 78% year-on-year.

It is this shifting dynamic at the nickel raw materials stage of the supply chain that has confounded nickel bulls and kept the nickel price under sustained pressure so far this year. Imports of aluminium were, along with lead, the only ones to rise at a commodity metal level.

But the 44,000-tonne year-on-year jump to 64,000 tonnes is but a drop in the aluminium ocean and dwarfed by the country’s exports of semi-manufactured products. Semis exports totalled 2.1mn tonnes in the first half of the year, up 6%.

Rather ominously in light of the current political heat around China’s role in the global aluminium market, exports were 400,000 tonnes or above in both May and June, a level that has only been seen twice before, once in June 2015 and once in December 2014.

Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.