Let’s say you’re the holder of the world’s largest reserves of conventional, low-cost crude oil and you believe the supply outlook is “increasingly worrying” due to a lack of investment. Enhancing production capacity so as to cash in when prices soar would seem like a good idea. Apparently not if you’re Saudi Aramco.

Saudi Arabian Oil Co CEO Amin Nasser spoke at the recent World Petroleum Congress in Istanbul, describing his company’s plans to invest $300bn over the next decade. But that cash won’t go toward boosting the rate at which Saudi Arabia can get oil out of the ground, even though as much as 20mn bpd of new output could be needed over the next five years to offset rising demand and the natural decline of fields that are currently in production. Instead, that money will be used to maintain current capacity, and double gas output.

Am I alone in seeing this as an odd response to the supply crunch Nasser sees looming?

Saudi Arabia sits atop 266.5bn barrels of proven oil reserves. That’s more than any other country, if you exclude the extra-heavy crude in Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt. At under $9 a barrel, the cash cost of production is the lowest in the world, according to consultants Rystad Energy. To me, this screams, “drill, baby, drill.”

I would go further and argue that Saudi Arabia should be opening its upstream oil sector to foreign or local private investors – under carefully controlled conditions, of course. If Mexico can do it after almost 80 years, then why not Saudi Arabia? Yes, I know there are issues of national pride and memories of unfavourable concession terms from the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, but these are battles of the past, not of the dynamic, forward-looking nation that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman wants to build.

Just look at the impact that foreign investment has had on Iraq, and think what the opportunity to invest in Saudi Arabia would do to the attractiveness of alternatives in Iran.

Why wouldn’t Saudi Arabia position itself to reap the rewards of the industry’s failure to invest in boosting oil production capacity?

There are a number of possibilities.

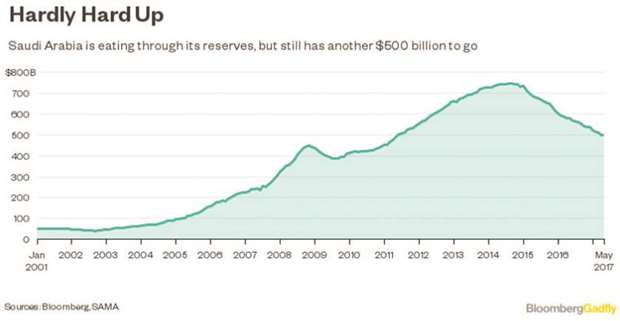

It can’t afford to raise upstream capacity on top of its other plans. This would seem unlikely. While Saudi Arabia has certainly been hurt by the halving of oil prices since 2014, financial reserves are still plentiful and it could redirect part of its planned investment budget to developing known oil reserves.

Reserves aren’t as big as reported. This is a long-running claim by those who point to the big jumps in oil reserves disclosed by Opec countries in the 1980s when they were a factor used to determine output quotas.

A former colleague, who previously worked in both Opec and the Iraqi oil ministry, argues that the revisions corrected previous under-reporting of discoveries there had been no incentive to divulge.

Don’t expect the Aramco IPO to shed any light on the matter, either; there won’t be anything like a full audit of Saudi oil reserves in the foreseeable future.

Decline rates at existing fields are so steep that Aramco must run as fast as it can just to stand still. This was certainly a popular theme a decade or so ago when Matt Simmons published his book Twilight in the Desert, but one that has found few supporters in recent years.

Maybe Nasser doesn’t believe his own story of a future oil shortage and if the need for additional Saudi capacity doesn’t exist, then there’s no point investing in it. He wouldn’t be alone in that view. The “new normal has emerged,” India’s Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan said in an interview at the same event in Istanbul. “This is a reasonable price for everyone.”

I have no idea which, if any, of the above is closest to the truth. But I’m sure everybody will have their own favourite, and probably plenty more besides.

* Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg First Word. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners. The views expressed are personal.

.