A friend and I were standing on a corner waiting for the light to change, talking about the FX series Feud. “Isn’t it great,” he said, “how much it winds up on Joan Crawford’s side?” Yes, but no, I started to reply, but before I could we crossed and the conversation turned away. I wondered if what we saw in the show was a kind of Rorschach test. Who’s the hero: Joan Crawford or Bette Davis?

Being Team Davis, when I stumbled across a paperback of her memoir, The Lonely Life, I bought it, brought it home and promptly started reading. As The Los Angeles Times’ book editor, you might expect me to be reading Plutarch’s Lives in my spare time — but Hollywood lives are far more interesting.

You don’t have Los Angeles history without Hollywood history. The entertainment industry found a new home led in part by theatre business rascals slyly getting as far as they could from Thomas Edison in New Jersey, who was trying to enforce his motion picture patents. In Los Angeles, they found a safe distance, lovely weather and light that was particularly suited to the new medium. You may know all that: It’s part of the many terrific, straightforward, deeply researched histories and biographies I’ve read.

Memoir is another matter. Idiosyncratic and biased, obfuscatory and boastful, even unctuous and vain, the Hollywood memoir is not going to portray the past in a clear light. But like Sriracha on the table, it’s going to bring the heat and make the meal better. So much better.

Davis’ career was at its nadir when The Lonely Life was published in 1962. That fall, the two-time Oscar winner shocked Hollywood by taking out a want ad in the trades soliciting acting work. A few weeks hence and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? would open, making her once again a critical and box office favourite. But this was the dark before that dawn: The Lonely Life was written at the close of 10 “black years,” as Davis called them, at the end of her fourth marriage, living in all but exile from Hollywood — written, in other words, when she had nothing to lose.

In the book, Davis shines when telling the story of her youth, of her single mother’s rule-bending efforts to make a home for her two daughters; when she outlines her own fixation and determination to be an actress, something her mother obsessively supported; and when she takes others to task. Her targets include the brothers Warner, method actors and Hollywood men.

Davis later maintained that the title The Lonely Life was meant to refer to theatrical actors in general, not her personally. You might believe her. She was married four times and was exasperated by her romantic prospects and her husbands (particularly the bandleader, the admirer and the actor) who, when eclipsed by her professionally, felt emasculated and betrayed her. And she always eclipsed them.

Davis won a lead actress Oscar in 1936 for Dangerous and in 1939 for Jezebel, and while she was nominated eight additional times, those two titles alone give a fairly accurate sense of her screen persona. As an actress, she excelled at strong roles, although she wasn’t always given them at her home studio, Warner Bros., with which she had headline-grabbing contract disputes. In the book, she wisely brushes past the legal details, instead recounting falling in and out of favour, feeling slights and making demands.

It’s fascinating to read her puzzling through and defending her choices — her work always came first — particularly because she had no Hollywood model to follow. The movie industry had gone through a major sea change just before her arrival, shifting from silent film to sound. That opened the doors to actors trained in theatre, like Davis, while most of the silent cohort, whose dramatic style was considered passé packed up and went home.

That’s what happened to Colleen Moore. She was known as the original film flapper and was the top box-office draw in 1926; eight years later, her final film was released. When she’s remembered now (if not confused with imitators Clara Bow or Louise Brooks), it’s for her bob haircut and electric smile. She didn’t bother writing a memoir until 1968; Silent Star is now out of print.

I found a copy last month at an estate sale in a rambling, once-grand house destined to be torn down. Among the medical books and photography manuals was a hardcover edition of Silent Star, and I saw it was signed. Not by Moore, though. “To Lilliam,” it read, to the woman who’d lived there. “In memory of the days on So. St. Andrews when you ‘were’ Billie Dove and I was Jean Harlow.” That — the friendship with its silver screen echo — was what lured me in.

When I got home, I ploughed through Moore’s book. Lighthearted and anecdotal, she recalls her Hollywood days with clarity but seems, with the distance of the intervening decades, to no longer be in their thrall. She begins swiftly dispensing with the Hollywood myth that she’d been discovered by D W Griffith — her contract was a payoff for a debt owed her uncle, she writes, joking that even the press man who cooked up the lie eventually came to believe it.

She was just one of a bevy of hopeful starlets, making her first film in 1917 and struggling to match Mary Pickford’s innocent long-haired beauty. After years of intermittent, moderate success, she read the flapper novel Flaming Youth and begged for the part in the film. Her mother bobbed her hair to prove to the studio that Moore was right for the part. Her look was revolutionary on-screen — legend has it that audiences gasped — and her energetic, modern persona was that of the new generation. The film rocketed her to stardom.

The work was a whirlwind. Her marriage to a Hollywood filmmaker who was a desperate alcoholic was rocky. Between the personal anecdotes, Moore (or a less interesting ghostwriter) shares stories of the silent era — others’ love affairs and heartbreak, the Fatty Arbuckle scandal, the murder of William Desmond Taylor. Moore doesn’t detail her departure from Hollywood (after a few years, she found a happy life with a Chicago businessman) but instead focuses on an unusual side project that absorbed her during her transition to her new life.

She called it the Fairy Castle; it was a massive, exquisitely constructed dollhouse that she took on a national tour to raise money for charity. There is, yes, too much ink spilled over the real jewels in it, the craftsmen who created it and so on, but without all that folderol she wouldn’t have gotten to its library. It contained an autograph book the size of a postage stamp actually signed by Orville Wright, Henry Ford, US presidents and Albert Einstein. And also tiny books with original handwritten stories by 20th century greats, including Sinclair Lewis, John Steinbeck, Edna Ferber and Willa Cather.

In the miniature copy of This Side of Paradise, F Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “I was the spark that lit up Flaming Youth, Colleen Moore was the torch. What little things we are to have caused all that trouble. My author’s name is F Scott Fitzgerald.”

I was surprised to see Fitzgerald pop up in the middle of a memoir by a silent film actress and delighted to see a playfulness that was lacking in his later life. So perhaps I could say that I’m reading for work. That this was bookish after all.

But not really. My guilty reading pleasures this summer are Hollywood stories. I love the strange window they provide into our city; the industry that created it; and the trials of women who were determined to create their own destinies when there was no path in sight.

These two books are by no means comprehensive. I could, and I have, created coherent lists of early Angeleno entertainer autobiographies.

But this summer, I’m reading the serendipitous books on the shelf for their un-indexed surprises. And I’m imaging Fitzgerald poised with a fountain pen over a book not even an inch tall, figuring out what to write to the dynamic actress that he felt in cahoots with, as if they’d turned the world upside-down. Picturing Davis with her unsatisfied ego pounding in her chest, putting it all down on paper, thinking no-one would ever care for her again, just before they did.

It’s every writer’s project: connecting with an invisible thread. Reaching a reader who cares. Telling the truth, but on a slant, in the light particularly suited to our city, Los Angeles. —Los Angeles Times/TNS

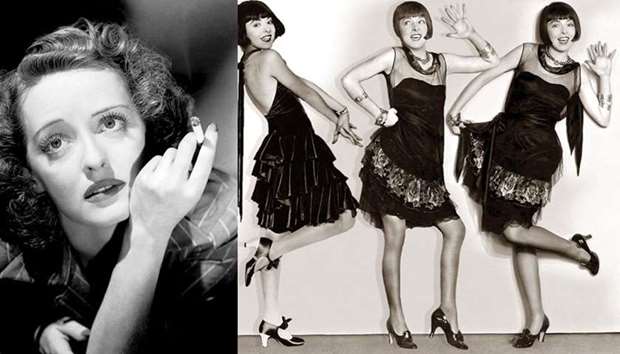

SUAVE: Bette Davis. Right: BLAST FROM THE PAST: Colleen Moore in 1929 starrer Synthetic Sin.