By 2025, foreign-exchange dealing in G10 currencies - which account for the overwhelming majority of the $5.1tn-a-day market - will become fully electronic, predicts David Mercer, chief executive officer of LMAX Exchange, an electronic trading platform. Already in 2015, about 76% of global currency trading was done electronically by the biggest and most active investors, according to consulting firm Greenwich Associates.

Demand for greater transparency in pricing and fees has helped accelerate the shift, along with banks’ efforts to cut staff and lower costs more broadly since the global financial crisis. In Asia, however, thinner volumes mean there’s less scale to be gained. Idiosyncratic markets also have an impact: when it comes to relatively illiquid currencies like the Vietnamese dong and Indonesian rupiah, for example, investors may prefer checking in with a human trader.

“Speed is not so important in Asia,” Mercer said. “Price discovery is not so easy because most of the dealing still happens in London, Chicago and New York.”

Humans have been on the retreat in financial markets for some time - the open-outcry commodity pits showcased in the Eddie Murphy film “Trading Places” have almost disappeared, for example - and equity markets too are now predominantly electronic. But people have kept their role in the foreign-exchange market longer because most trading has taken place away from exchanges.

In Asia, a penchant by policymakers to influence, if not control, their exchange rates makes it tougher to see a switch- over to electronic trading. Thailand’s central bank will hold a briefing on Monday to announce foreign-exchange regulation reforms. Local restrictions mean investors often use offshore markets for non-deliverable forwards to hedge against losses or speculate on declines in currencies. Due to their complexity, NDFs are typically handled by phone between human traders.

That didn’t stop NEX Markets from setting up an electronic market, but its platform took a blow when it came to the ringgit. Since Malaysian regulators in November took steps to deter foreign banks from trading offshore ringgit NDFs, trading on the platform for that instrument tumbled 70%, said Jeff Ward, head of Asia and emerging markets.

“Political headwinds will mean that it has a natural slower rate of uptake than maybe it would do otherwise,” Andrew Bresler, director for global sales trading at Saxo Capital Markets in Singapore, said of electronic trading. “Liquidity providers don’t want to go and upset the central banks.”

Asia’s not alone in lagging behind US and European markets in electronic trading - Latin America continues to be dominated by the telephone, according to Ward at NEX Markets. That region is “like Asia eight years ago for us,” he said.

As with driverless cars, some traders see dangers from electronic trading - read more about that risk here.

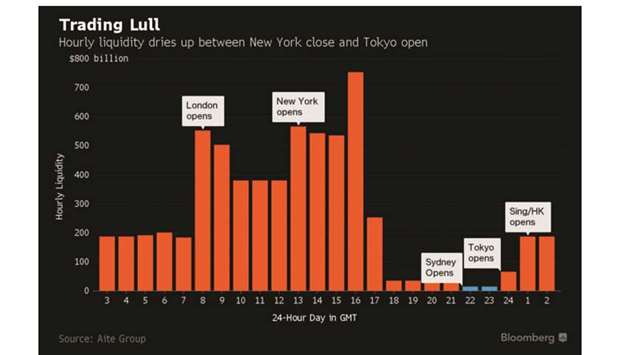

“Relationship trading will remain important” in many areas, said Javier Paz, a senior analyst in Boston at the consulting firm Aite Group. But the inevitable march of the machines is being propelled by banks continuing to cut costs as regulatory changes compress their margins - the 12 largest global banks slashed front-office staff, including sales and trading, by about 25% in G10 currency markets from 2012 to 2016, according to Coalition Development Ltd.

Ultimately, “increases in trading volume and electronification will have a positive effect on liquidity,” Paz said.