The Trump trade agenda could keep global trade growth depressed in coming years, QNB has said in an economic commentary.

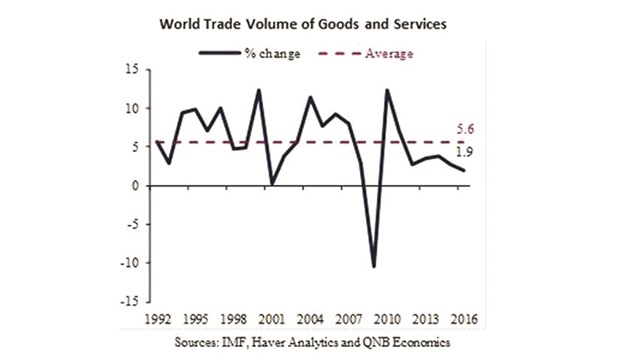

According to QNB, the global trade has had a torrid few years, with its growth hovering well below its historical average and decelerating further to 1.9% in 2016.

There are two planks to ‘Trumponomics’ — trade protectionism and fiscal stimulus through tax cuts and infrastructure spending, the report said. While fiscal stimulus should be “positive” for the US and the rest of the world, trade protectionism could be “highly disruptive and even risks sparking a global trade war”.

Since his inauguration on January 20, Donald Trump has pushed forward on the trade protectionism front, but fiscal stimulus has taken a back seat. A continuation of the recent downward trend in global trade growth, therefore, appears likely.

Trump has already taken concrete steps towards trade protectionism. On his first full working day in office, Trump formally withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The deal, which would have lowered tariffs in countries that account for 40% of global GDP, is unlikely to be replaced by such a large trade deal in the near future.

In addition, Trump has announced that he plans to renegotiate the North Atlantic Free Trade Area (NAFTA) and proposed placing tariffs of 45% and 35% on China and Mexico respectively as well as a general tariff on all US imports. However, due to political expediency, the most likely proposal to be implemented is a “border adjustment” as part of a new corporate tax code.

The border adjustment would be a change from the current corporate tax system as export revenue would be exempt from taxable income and imports would no longer be deductible as a cost. The aggregate effect would be the same as an import tariff combined with an export subsidy that means companies will only be taxed on their domestic revenue and costs.

In a simplified example, under the current system, a company with total revenue of $100mn and costs of $60mn would be taxed on its total profit of $40mn. Under the proposed system, if $40mn of the company’s costs were imports, these would be added to the company’s tax base to make it $80mn.

However, if the company also received $30mn of export revenue, this could be used to offset the tax liability, reducing it from $80mn to $50mn. As the US runs a trade deficit, foreign net profits are negative.

Therefore, the proposed tax would increase the government’s revenue by expanding the tax base.

The new tax should increase import prices, leading to a narrower trade deficit, faster US GDP growth and higher inflation. However, these initial effects would be offset by two factors.

First, the dollar is likely to appreciate due to a narrower trade deficit and higher US interest rates in response to rising inflation. This would make imports cheaper and exports less competitive, partially offsetting the initial impacts of the border tax on the trade deficit, growth and inflation.

Second, tariffs are likely to disrupt US supply chains. It will take time for US firms to replace foreign intermediate goods and services with US products. This could erode the remainder of the potential benefits of the new tax code.

Looking beyond the US, the impact for global trade will be decidedly negative. The disruption of supply chains is not confined to the US.

For example, many of the inputs into making cars in Mexican factories originate from the US as exports. Shutting down Mexican car factories will, therefore, both reduce imports to the US and exports from the US.

Furthermore, the biggest risk to global trade comes from the fact that other countries are likely to see the new tax as a tariff in disguise, in breach of world trade rules, making retaliation highly likely, QNB noted.

“Many of the US’s largest trading partners are likely to implement tariffs on US products or take other retaliatory measures. Therefore, any US export gains would be limited and the hit to global trade would be exacerbated,” QNB said.

Business / Business

Trump trade agenda may keep global trade growth ‘depressed’ in coming years: QNB

EME