China may have put a few short-term currency speculators to the sword last week, but long-term investors betting against the yuan are still standing, and they carry much more firepower.

An abrupt tightening of yuan liquidity in Hong Kong, which traders believe was orchestrated by Chinese authorities, drove overnight rates on the offshore component of the yuan to record highs above 80% and made it prohibitively expensive for punters to borrow and short-sell the yuan.

That pulled the offshore yuan from lifetime lows near 7 per dollar, but did not alter expectations for the yuan to depreciate this year.

Traders also suspect that while some of the hedge funds that routinely borrow short-term funds to speculate on the yuan might have been forced to square off their trades last week, the yuan bears are mostly longer-term funds with staying power.

“A lot of hedge funds do fund themselves overnight, but most people are in the three-month plus area, and it doesn’t affect them,” said Richard Benson, co-head of portfolio investment with Millennium Global in London.”Spot movement is spot movement, and you aren’t forced to do anything.”

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) hasn’t explicitly confirmed it was behind the squeeze that drove interbank overnight CNH rates to 87% last Friday, from 4% a week earlier, and caused the biggest ever weekly gain in the offshore yuan against the dollar – just under 2%.

But that is the assumption of market professionals.

“All they wanted to do is to create some uncertainty and to make sure that investors don’t think the yuan is a one-way street,” said Jean-Charles Sambor, deputy head of emerging market fixed income at BNP Paribas Investment Partners in London. “It wasn’t a game of trying to wash out the CNH shorts, but it was a good way to ring the bell.”

Sambor reckons the PBoC’s actions were less targeted at any specific investor type and more about managing capital outflows from China, particularly at the turn of the year, when the annual $50,000 foreign currency conversion quota is reset for domestic individuals.

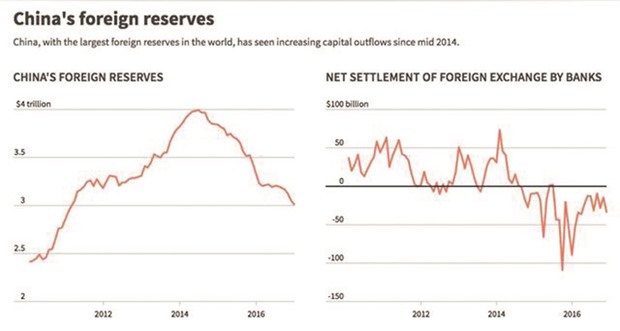

The outflow of capital has been one of China’s biggest policy challenges since 2016, driven by a declining trade surplus and direct investment flows as well as an outpouring of retail money seeking yield abroad.

China’s currency reserves fell $319bn in 2016 as it tried to slow the decline in the yuan.

Even so, it had its worst year since 1994, dropping 6.6%, and the market is pricing in a 4% decline in the coming year.

There’s no hard data on market positioning in the yuan, although a Reuters poll of positions in various currencies shows investors have been consistently shorting the yuan since September last year.

Fund managers suspect a lot of the short positions were placed after Donald Trump won the US presidential election in November, having campaigned on expansionary fiscal policies, and as the Federal Reserve hinted it would raise interest rates at least three times in 2017, all of which should boost the US dollar.

The logic of that long-dollar, short-yuan position was not changed by last week’s turbulence.

“The long-dollar trade was a consensus trade by real money and by global macro funds, so it wasn’t a huge leveraged play on yuan weakness,” Sambor said.

China’s slowing economy and the creeping liberalisation of its capital account further entrench expectations for yuan depreciation, and will keep up pressure for policymakers to spend reserves to slow the fall.

“If they step away from the intervention to support the yuan and let it fall, it would likely spur a speculative attack,” wrote Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman.

That would increase trade tensions while also hurting the economy.

“There may be no good options with the yuan. Slowing the decline can be costly. Allowing the full decline would be disruptive,” Chandler wrote.