Single-mother Li Ying helps explain why household debt in China may be a bigger risk to the giant economy than previously thought.

Faced with expensive medical bills to treat breast cancer, the 38-year-old nurse from Heilongjiang in northern China is struggling to repay her mortgage and relies on financial support from her wider family to pay for her healthcare.

To cut household costs, she waits until the local food market is about to close before buying because that is when remaining fresh produce is sold at a discount.

“People say that when it’s about to close is the time that produce is cheapest,” said Li. “So now I go at that time.”

Li’s experience show’s the vulnerability of Chinese consumers, who are taking on record amounts of debt even as income growth slows, adding to the challenge for policymakers of preventing the economy from slowing too quickly.

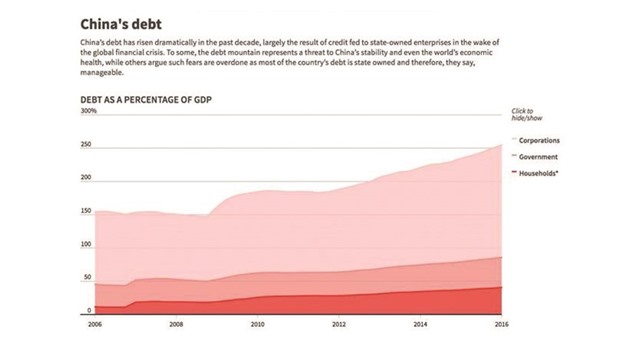

China’s household debt as a proportion of GDP has more than doubled to 40.7% in less than 10 years. While developed nations have higher rates of household debt, Chinese families are much more leveraged because income is lower and so proportionately the costs of social welfare from pensions to healthcare are much higher.

At the end of 2014, the out-of-pocket health spend in China as a percentage of total expenditure was 32%, compared to 9.7% in Britain and 11% in the United States, World Health Organisation data shows.

“Household debt leverage is very alarming, even though the aggregate amount is controllable,” said Wan Zhe, chief economist at China National Gold Group Corp, visiting researcher at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. “The first issue is that household debt has risen too quickly, the second is that it has risen too quickly as a proportion” of GDP and disposable income, said Wan.

Underlining these concerns, authorities are trying to calm a property rally.

In the latest move, regulators told banks to limit the issuance of home loans, the Shanghai Securities Journal reported on Thursday.

The balance of retail mortgages at the end of the third quarter hit 16.8tn yuan ($2.5tn), more than a third higher than a year earlier, China central bank data shows.

More broadly, consumer debt financed by Chinese banks has grown sharply, from 3.8tn yuan at the end of 2007 to 17.4tn yuan at the end of last year, a compound annual growth rate of 21%, Fitch Ratings said in a report.

But the growth in income has been much more modest, rising 6.3% in January to September compared with the year-earlier period, the weakest pace since 2013 when the National Bureau of Statistics first started issuing the data. “The rapid growth in outstanding (consumer) loan balances has been accompanied by an increase in NPLs (non-performing loans) across all segments of consumer debt,” the Fitch report said.

China’s central bank did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Like a typical borrower, half of Li’s 2,800 yuan in monthly earnings cover her mortgage payments, with 200,000 yuan outstanding.

That proportion rises to 70% though in first-tier cities, where prices have been rising the fastest, said Yan Yuejin, director of E-House China R&D Institute.

But the cost of treatment for breast cancer has dramatically changed Li’s financial position. Since February last year, she has spent around 132,000 yuan on the treatment and has to continue with medication for three years at 6,000 yuan a month just for drugs. Most of the medical bills are paid by her family.

“Things have changed, I didn’t used to think money was that important,” said Li. “Before, if there was 1 yuan on the ground I wouldn’t pick it up, now even if there is 1 fen I will pick it up,” she added.

There are 100 fen in one yuan.

Public health insurance reaches nearly all of China’s 1.4bn people, but its coverage is basic, leaving patients liable for about half of total healthcare spending.

That proportion rises further for serious or chronic diseases such as cancer.

Some economists argue that China’s gross savings rate of 49% of GDP at the end of 2014 suggests little risk to the economy from the buildup in household debt. But Michael Pettis, a professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management Peking University, said there are hidden problems.

Down payments for new homes, which are relatively high in China, are often borrowed from family members.

“We can’t simply assume there isn’t any debt there, or that it’s family debt and mom is never going to foreclose on you so it’s OK,” said Pettis.

Highly indebted households also cut their spending more in a downturn, which can make a slowdown worse, economists say. Beijing wants consumption to help drive future economic growth as it turns away from its traditional manufacturing base. Retail spending growth is easing however.

BEIJING