“Sab ka khushi se fa’asla ek kadam hai/ Har ghar mein bas ek hi kamra kam hai (Everyone is just one step away from happiness/ Every house needs just one more room).”

One of the advantages of talking to a poet or an intellectual is that they would put things so lyrically into perspective, it is impossible to misconstrue. So does the architect of the above couplet, Javed Akhtar.

Just as the two lines preeminently describe the philosophy of distance and the happiness that lies at the end of such an expanse, Akhtar sums up the relationship between his native India and Pakistan from a solution frame of reference, and not the problem one. After all, everyone knows what the problem is.

“It is the regions that grow in the world. You name one country that has two poor countries in its neighbours. Impossible! Our region (sub-continent) must also realise that they have to climb this stair of development and growth together,” Akhtar tells Community.

The great contemporary Urdu poet from India was once again in town after more than two decades. He was here to receive an award for his services to Urdu through his poetry by Majlis Farogh-e-Urdu Adab Qatar.

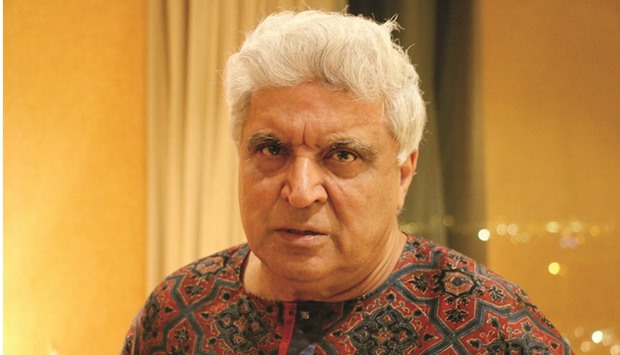

Donning a long printed black kurta with white pajamas, his grey hair appropriately yet casually combed back on his head, Akhtar is ensconced in his hotel room sofa, all set to be among fellow poets and writers for a dinner reception.

“It is a pity that the countries where so many children do not go to school, where so many people do not get medical aid, people do not have shelter; these countries are the biggest buyers of conventional weapons,” he observes.

Watch out! Almost all his talk here will be lyrical, mostly rhyming yet emphatically within the boundaries of easy interpretation.

“This is the real tragedy. And they (India-Pakistan) indulge ‘non-issues.’ It (recent tensions) is very unfortunate. This is a kind of traumatic relationship that keeps on blowing hot and cold but I do not remember any time it was an ideal relationship. And it is sad,” says Akhtar, who is not just an award-winning poet, lyricist and screenwriter, but an avid commentator on everything from politics to films, and social issues.

“By the end of World War II in 1945, these European countries were bombing each other’s cities out of existence. Look where they are today. They have common economic markets, a common currency and you can walk into one country from another,” he points out, hinting if they can achieve it, why India and Pakistan cannot.

Once the quintessential India-Pakistan talk is over which consumed most of the promised interview time, we move on to discuss his recent absence from the Indian film scene, the growth of Bollywood in general besides literature in Urdu and other languages’ future in the age of technology. You can talk to him on such subjects for hours, tirelessly.

Akhtar was awarded the civilian honour of Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1999, followed by the Padma Bhushan in 2007. In 2013, he received the Sahitya Akademi Award in Urdu, India’s second highest literary honour, for his poetry collection entitled Lava.

“As a consequence of the successful movement for copyrights of writers and poets that I initiated six or seven years ago in India, I have not been much popular with music companies and producers. As a matter of fact they boycotted me,” Akhtar says to explain his apparent absence from film and music scene.

However, he successfully executed a long movement to bring about amendments in the law administering copyrights of writers, poets and musicians; making India one of the best from one of the worst countries in terms of copyright laws for these people.

“Now there are a few companies and producers who are working with me and I am thankful to them. But I suppose now they will reconcile with the fact that everything is done, sealed, signed and delivered,” says Akhtar.

He comes from a family of poets, writers, artists and intellectuals. From his great grandfather to his father and mother, everyone carved a name in the literary and art world in Indian sub-continent. Akhtar himself is married to famous Indian actress Shabana Azmi, his son Farhan Akhtar and daughter Zoya Akhtar are actors and film directors. Popular Indian poet Kaifi Azmi was his father-in-law.

“Film songs are not made in a kind of void. They are ultimately part of a society. Everything that happens all around reflects in the films, even in what you call commercial films,” observes Akhtar.

Over the years, he goes on to explain, what has happened is that literature, language and fine arts have taken a back seat. “They are not very high on the list of priorities because everybody is running to catch the gravy train,” says the poet.

Akhtar, whom Professor Gopi Chand Narang, a writer and intellectual from India, credits for making poetry and literature more accessible to everyone, feels that language on the whole in India is shrinking in the society. There are fewer people who have understanding of poetry today.

“Technology cannot produce great poets. Technology can take poetry and make it accessible for everybody. It can make you reach a larger audience. But then there should be a willing audience, a willing readership,” says the Indian poet and lyricist, explaining why technology cannot compensate for the lack of interest in good literature.

“Technology cannot produce art, technology can expose it,” says Akhtar.

Commenting on the current state of Bollywood, the Indian film industry, he says the growth has not been linear. “Life offers you packages. They all have their good and bad. You keep wondering which is the better package,” he says in a prelude to the Bollywood journey.

Technically, Indian films have improved greatly, becoming more professional and the variety of stories available today is unbelievable. This variety was not available in 50s to 70s.

“At the same time, what is missing are the social concerns; the intellectual depth. But I suppose it was inevitable and that it would come back, that is also inevitable,” Akhtar explains.

The rebound of intellectual depth will happen perhaps, in another 10 years as it happened after 1980s that Akhtar considers the dark ages of Bollywood. This phase, too, will be over, he predicts.

As we wind up the conversation, it all could be summed up in Javed Akhtar’s lines immortalised by Pakistani maestro Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s voice in 1996.

“Jaanta hoon main tum ko shauk-e shaayari bhi hai; Shakhsiyat sajaane mein ek ye maahiri bhi hai, Phir bhi harf chunte ho, sirf lafz sunte ho; In ke darmiyaan kya hai, tum naa jaan paaoge.”

(I know you have a flare for poetry, it is one way of adorning one’s personality. Yet you choose and listen only to words; what lies between them, you would never get to know).

CANDID: Javed Akhtar says regions grow together and that the subcontinent should take heed. Photo by Umer Nangiana