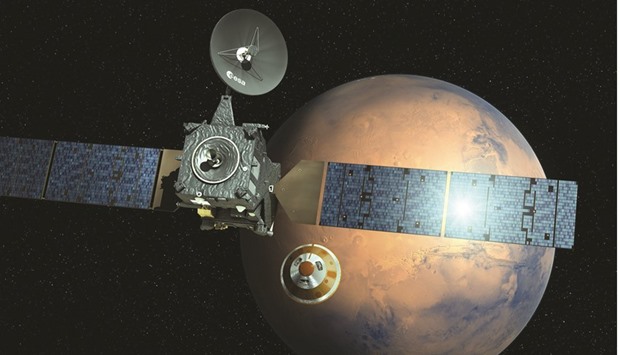

A Mars lander left its mothership yesterday after a seven-month journey from Earth and headed towards the red planet’s surface to test technologies for Europe’s planned first Mars rover, which will search for signs of past and present life.

The disc-shaped 577kg Schiaparelli lander separated from spacecraft Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) at 1442 GMT as expected, starting a three-day descent to the surface.

But in a setback, signals received from TGO, which is to orbit Mars and sniff out gases around the planet, did not contain data on the lander’s onboard status, raising.

Ground controllers were eventually able to re-establish full links however.

“Everything is back on track,” spokeswoman Jocelyne Landeau-Constantin of the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, told AFP by telephone, surrounded by “a lot of relieved people”.

“We have to receive and process this telemetry (data) first and after that we can say what has happened. But on the side of (Schiaparelli) I would say that the separation was a success,” Paolo Ferri, head of mission operations at the European Space Agency (ESA), told Reuters TV.

Schiaparelli, part of the European-Russian ExoMars programme, represents only the second European attempt to land a craft on Mars, after a failed mission by Britain’s Beagle 2 in 2003.

Landing on Mars, Earth’s neighbour some 35mn miles (56mn km) away, is a notoriously difficult task that has bedevilled most Russian efforts and given Nasa trouble as well.

The United States currently has two operational rovers on Mars, Curiosity and Opportunity.

But a seemingly hostile environment has not detracted from the allure of Mars, with US President Barack Obama recently highlighting his pledge to send people to the planet by the 2030s.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is developing a massive rocket and capsule to transport large numbers of people and cargo to Mars with the ultimate goal of colonising the planet, with Musk saying he would like to launch the first crew as early as 2024.

The primary goal of ExoMars is to find out whether life has ever existed on Mars.

The current spacecraft, TGO, carries an atmospheric probe to study trace gases such as methane around the planet.

Scientists believe that methane, a chemical that on Earth is strongly tied to life, could stem from micro-organisms that either became extinct millions of years ago and left gas frozen below the planet’s surface, or that some methane-producing organisms still survive.

The second part of the ExoMars mission, delayed to 2020 from 2018, will deliver a European rover to the surface of Mars.

It will be the first with the ability to both move across the planet’s surface and drill into the ground to collect and analyse samples.

The ExoMars 2016 mission is led by the ESA, with Russia’s Roscosmos supplying the launcher and two of the four scientific instruments on the trace gas orbiter.

The prime contractor is Thales Alenia Space, a joint venture between Thales and Finmeccanica.

The cost of the ExoMars mission to the ESA, including the second part due in 2020, is expected to be about €1.3bn ($1.4bn).

Russia’s contribution comes on top of that.

This photo taken from the ESA website on March 1 shows an artist’s impression depicting the separation of the ExoMars 2016 entry, descent and landing demonstrator module, named Schiaparelli, from the Trace Gas Orbiter, and heading for Mars.