Maybe it’s because it’s the lead market. If a warehouse company had submitted incorrect copper stocks figures to the London Metal Exchange (LME) for three weeks, it might have expected a bigger fine than £30,000 ($40,000).

Which is what Worldwide Warehouse Solutions (WWS), the LME logistics arm of Noble Group, has been hit with for supplying wrong lead stocks figures for metal stored at the Dutch port of Vlissingen.

But this is lead we’re talking about.

And although the original misreporting fiasco back in February and March enraged lead traders, it’s not the sort of story to generate outraged headlines in the mainstream media. Still, at least we get an answer to the riddle of what exactly happened with those phantom lead stocks, which simply weren’t there.

The first anyone knew that all was not right with the LME lead stock count at Vlissingen was on March 8, when the exchange issued a short notice to members titled “Vlissingen Stock Correction”. “Please note that 31,700mt (metric tonnes) of Lead in Vlissingen will show in the stock report published 09 March 2016 as a delivery out.

Please be advised this is not a physical delivery out but a correction of an earlier error in reporting by the Warehouse.”

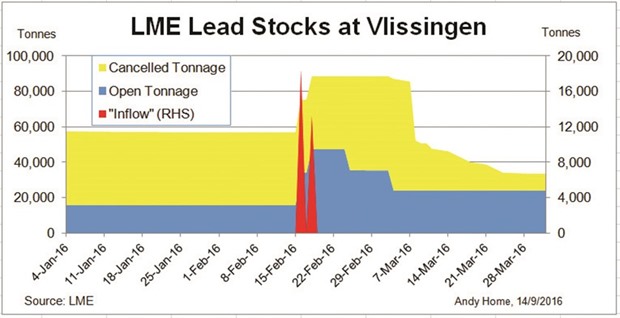

The tonnage corresponded to two apparent “inflows” of lead, the first of 18,425 tonnes, the second of 13,275 tonnes, in the LME daily stocks reports of February 17 and February 19 respectively.

Cue much head-scratching among the relatively small community of physical lead traders active in the LME market.

Although relatively large, the original “arrivals” were not out of keeping with lead stocks movements at the time, given a protracted “warehousing war” that saw large tonnages taken out of the system only to be relocated at Vlissingen and the South Korean port of Busan.

However, these particular “arrivals” were no such thing. Rather, WWS incorrectly instructed its London agent to issue new warrants for 1,268 lots of lead, when it should have told it to reissue warrants for metal that had previously been cancelled.

That would have simply rebalanced the ratio of cancelled to open tonnage and left total registered tonnage at Vlissingen unchanged at 56,725 tonnes.

Instead, it looked as if fresh metal had arrived, lifting Vlissingen lead stocks by 56% to 88,425 tonnes.

It took WWS three weeks to realise there had been a mistake, at which stage it notified the LME, which then issued its unenlightening notice.

The LME has now reached an agreed settlement with WWS, whereby the latter will pay that £30,000 fine and the costs of an additional audit to check the company has put in place new measures to stop a similar mistake happening in future.

WWS was found to have breached three clauses of the LME’s warehousing contract. The two most serious were Clause 11.1, requiring warehouse companies to conduct their business with “due skill, care and diligence”, and Clause 11.8, requiring an operator to “organise and control its affairs in a responsible manner, keep proper records (and) ensure that its employees or agents are suitable, adequately trained and properly supervised”.

The mitigating circumstances were that WWS had fully cooperated with the LME investigation, that the misreporting was down to “human errors”, that it had notified the exchange immediately on discovering its mistakes and that it had appointed an independent auditor to tighten its procedures.

Not mentioned is the fact that the wrong instructions were issued twice, that it took three weeks for anyone to notice and that the original misreporting may have actually generated a price reaction.

But then, this is only the lead market, not copper, or heaven forbid, aluminium, a market in which LME warehousing has grabbed the wrong sorts of headlines in recent years.

WWS is the third warehouse operator to be chastised by the LME in the last 18 months. And it’s tricky from the outside at least to calibrate the level of wrongdoing with the resulting fine.

The exchange will argue it judges each case on its relative merits, although the legal comparison doesn’t take into account the fact the LME is by necessity both judge and jury. However, the three incidents do fit into what might be tentatively termed the “I-Scale”.

CWT got whacked with a £100,000 fine in April 2015 for failing to disclose it had two trading entities within its extensive corporate group structure.

The LME said it had found no evidence that the lapse was deliberate or that any confidential evidence was passed between the warehousing company and the trading entities. In essence, CWT simply lacked a proper group organisational chart to show potential conflicts of interest of which it itself was completely unaware.

Right at the top of the disciplinary scale is infamy.

* Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.

.