Here’s the sofa on which Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev sat, happily sandwiched between Willy Brandt and Hannelore “Loki” Schmidt, with Helmut Schmidt perched on the end, the inevitable cigarette in his hand.

Brandt and Schmidt were West German chancellors.

Inviting the communist titan for a folksy visit to the Schmidts’ suburban home in Hamburg was a masterly stroke of diplomacy.

There’s still a whiff of menthol cigarette smoke around the house. That’s hardly surprising: Helmut Schmidt smoked incessantly here for five decades. Loki died in 2010 at 91, followed by Helmut, who had been chancellor 1974-82, at 96 five years later.

Their house has been preserved as it was during their lifetimes — a polished brass plate with the name “Helmut Schmidt” is still fixed above the doorbell — and is occasionally open to visitors.

The Schmidts bought the semi-detached pale-brick house in the summer of 1961. Loki later recalled them moving in with a hastily bought Christmas tree December, according to Heike Lemke, the archivist of the Helmut and Loki Schmidt Foundation.

At the time, Helmut was minister of the interior of the northern city-state of Hamburg.

Slowly the Schmidts began to spread out. They added an extension and then bought the row house adjacent to theirs.

The property now stretches out over what was once four plots with houses, according to Stefan Herms, director of the foundation.

The front door opens onto a high-ceilinged hallway at the end of which stands a black Steinway grand piano in front of floor-to-ceiling windows that look out onto a terrace.

Where the walls aren’t hidden by bookcases, they’re covered in pictures: works by the artists Nolde, Heckel, Heisig, Kokoschka, August Macke, Dali, Miro and Picasso.

“They’re originals, many of which are limited edition drawings and prints,” says Herms.

“It’s a remarkable collection, but no competition for an art gallery,” he adds.

The pictures fill the walls from the parquet flooring to the gabled ceilings. And there are ashtrays everywhere.

The walls of the living room, site of the plain Brezhnev sofa with its red leather cushions, are covered in books.

The shelves bend under the weight of coffee-table picture books and leather-bound volumes of history.

“Brezhnev sat here with Das Kapital by Karl Marx behind him,” says Lemke. “Helmut liked that.”

Helmut’s infamous chessboard stands on a table next to the fireplace, and beside it are two ornate chairs with the names of the players, Loki and Helmut, on the backrests.

The chairs were a present for Helmut’s 65th birthday, according to Lemke.

The living room is adjoined by “Otti’s bar,” a room where the Schmidt’s long-time bodyguard Ernst Otto Heuer served drinks when they had visitors.

Those visitors included US secretary of state Henry Kissinger and French president Valery Giscard d’Estaing.

“Helmut Schmidt was convinced that you had to personally get to know people and exchange views,” says Herms.

“Only people who had already passed certain tests were allowed in here,” says Lemke. “He had had long talks with them — and they smoked. Their sessions were legendary. It was tough luck for non-smokers.”

The brick bar has a maritime theme with pictures of sailors’ knots and brass lamps and model ships hanging from the ceiling.

There’s also a cartoon of Helmut Schmidt as Superman, “The Saviour of the Fatherland.”

On the bar there’s an almost 50-centimetre-high figure of Louis Armstrong; when you press a button it moves its head and blares out Hello Dolly.

“As well as art and intellect, you’ll also find a bit of kitsch here,” says Lemke with a shrug.

At their infamous Friday sessions, there was first a drink in the bar before the guests were called to the dining room, also decorated with pictures and heavy sculptures.

Who came and went here, how they behaved and what was discussed, Ursel Trebbin, who worked for 31 years as housekeeper for the Schmidts, must surely know.

But of course she’s not telling. “Nothing’s changed here, it’s as if they might come round the corner at any moment,” she says. “That would be nice.”

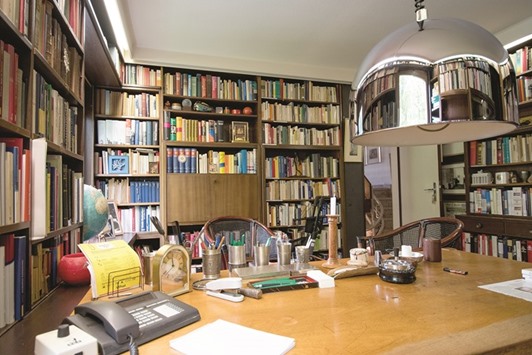

Helmut’s study is on the first floor, up the stairs by their stairlift, installed when the couple got old.

The almost square room is also full of books “mostly for work, but also encyclopaedias, [books on] political science, political philosophy,” says Lemke.

A large desk, on top of which are pewter pen holders, candle holders and of course an ashtray, dominates the room.

Behind it there’s a glass cabinet full of snuff tobacco tins and coins. And a small chess set that Schmidt carved when he was a prisoner of war.

“The black figures were dyed by dipping them in tea,” says Lemke. Helmut’s old, black briefcase still leans against the desk.

Back on the ground floor, the French windows are open. To the right is the swimming pool and to the left, camellias planted by keen gardener Loki which still bloom against the house wall in the spring.

The whole garden is Loki’s work. There’s also an extension housing her archive. She “wasn’t just the woman at Helmut Schmidt’s side,” says Lemke.

“She gave lectures and organised and financed an international exchange between botanical gardens.”

The house tour also takes in Loki’s greenhouse.

Opposite the house is the archive belonging to the Helmut and Loki Foundation.

Lemke estimates that the estate includes more than 25,000 books. In addition there’s also material from the office of Helmut, who went on to become the co-publisher of the German weekly newspaper die Zeit after being ousted from the chancellery.

There are boxes waiting to be unpacked everywhere.

One big room is dedicated to Helmut’s personal archive, which is made up of more than 2,500 files.

“It’s a very personal archive,” says Lemke. “Helmut Schmidt had had his press coverage monitored going back to 1953.”

There’s also letters, lectures, and other documents dating back decades, much of it handwritten.

It’s a treasure trove for historians, but much of the paper on which it is written is acidic, which means it is deteriorating.

“We first have to open up the whole archive and make sure we preserve it before the paper disintegrates,” says Lemke, describing the foundation’s immediate task.

Are there any digital records?

“Helmut Schmidt never used a computer. We’ve still got one foot in the Stone Age here,” she says.

But the foundation plans to drag the house and its archives into the 21st century this year by producing a virtual tour, since the property isn’t really suitable for making into a proper museum.

A few tours will still however be given from 2017, giving visitors the chance to step back in time. —DPA

Helmut Schmidt’s study at his home.