Bank regulators from Tokyo to Frankfurt are joining forces to resist a US-backed push for stiffer capital rules that could heap billions of dollars of new requirements on lenders.

Highlighting the stakes, top regulators from Europe, Japan and India are pressing their case in public, shedding light on divisions in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision as it races to wrap up work this year on the post-crisis capital framework. They want the global standard-setter to soften key proposals for how banks calculate the capital they need to finance lending and trading.

The proposals now on the table could result in an overall increase of as much as 70% in the capital banks must have, said Shunsuke Shirakawa, vice commissioner for international affairs at Japan’s Financial Services Agency, a member of the Basel Committee. Disagreement also exists on how much banks should be allowed to borrow against their assets and how far to limit their holdings of government bonds.

“If you add together all the proposals that have been made, it’s a significant increase no matter how you look at it, and that is a fact,” Shirakawa said in an interview late last month. “So there is a need to make adjustments by the end of the year.”

The US moved faster than the rest of the world after the 2008 crisis to revamp banking oversight, often seeking stricter standards than global minimums set by the Basel Committee. Daniel Tarullo, a Federal Reserve governor, has led the US argument that the proposals under debate this year are essential to preventing the industry from gaming rules by manipulating internal models lenders use to determine their own capital levels.

The Basel Committee promised in January not to boost capital requirements “significantly” as it wraps up work this year on bank-leverage limits and a revision of the way credit, market and operational risks are measured. The regulator describes this as putting the finishing touches on the framework known as Basel III, put in place after the crisis.

The financial industry, which has lobbied aggressively in recent months, says the overhaul is so far-reaching that it amounts to a new wave of regulation – Basel IV. Iain Mackay, group finance director of HSBC Holdings, said in May that lenders would be “pretty much stuffed” if Basel sticks to its plan.

The industry’s concerns are now shared by the regulators, and Shirakawa isn’t alone in his insistence that the Basel Committee keep its word. European Union finance ministers have made clear they expect the rules to come in as advertised. Valdis Dombrovskis, the EU’s financial-services chief, said Europe needs to “speak with one voice” to influence decisions at Basel, where nine EU countries, as well as the European Central Bank, have seats at the table.

The Basel Committee brings together regulators from nearly 30 countries, including Japan’s FSA, the ECB, the US Federal Reserve, the People’s Bank of China and the Brazil’s central bank. The committee reports to the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision, chaired by ECB president Mario Draghi.

Jonathan Hill, a former EU commissioner for financial services, said earlier this month that the EU’s executive arm would write to Draghi to ask for Basel plans such as the leverage ratio and fundamental review of the trading book to be “looked at again.”

The Basel Committee’s attempts to restrict banks’ use of internal models for risk-assessment, in favour of prescribed formulas, has proven particularly divisive.

The clampdown is in line with US views. The Fed’s Tarullo has said regulators should consider “discarding” the internal-model approach to risk-weighted capital requirements altogether in favor of a one-size-fits-all standard for all global banks.

That contrasts with the prevailing view in Japan and Europe. Shirakawa said an increasing reliance on the standardized approaches could hamper effective risk-management by the industry and may provide banks with a “perverse incentive” to take too much risk in some cases. Elements in the regulator’s main proposals are “too conservative,” he said.

“Quite a few have the same view as I do,” said Shirakawa. “On the other hand, quite a few argue strongly that, based on the experience of the financial crisis, you can’t place too much faith in banks’ internal models, and that some banks abused the models to keep their capital requirements artificially low.”

Another battle ground is the leverage ratio, promoted by the US and viewed more skeptically in Europe and Japan. The Basel Committee has already agreed on a 3% minimum level, and is considering setting higher requirements for the world’s most systemically important banks, including Japan’s Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group.

“We think that the 3% is suitable and there is no need to go a lot higher,” Shirakawa said. If Basel Committee members insist on an increase, then a bucketing approach, whereby charges increase along with the global importance of the bank, would be preferable, he said.

Shirakawa said the risk-blind leverage ratio is intended as a backstop for the risk-weighted capital rules, and is useful when banks can’t reliably measure risk. “If the backstop is always binding, that is abnormal,” he said.

He has an ally in Daniele Nouy, head of the ECB’s oversight arm, who has also called for risk-sensitivity in the new standardised approaches to measuring risk. Japan is also wary of bank regulators imposing restrictions on lenders’ holdings of sovereign debt. That puts it in line with India, which opposes potential restrictions. The Basel Committee has moved more slowly on such curbs. Raghuram Rajan, governor of the Reserve Bank of India – another Basel Committee member – said his country is pushing back hard on the restrictions.

“We are opposing that tooth and nail at Basel,” Rajan said.

While the sovereign-debt issue is likely to run for years, the work on Basel III is supposed to be done by December.

That leaves Shirakawa and his allies with a lot to do in a very short time. Nouy said last month that an “overwhelming majority around the table” in Basel supports minimising any increase in capital charges as a result of the latest plans. Shirakawa shares that objective.

“There’s half a year left, so there’s sufficient time,” he said. -With assistance from Jeanette Rodrigues and Sandrine Rastello.

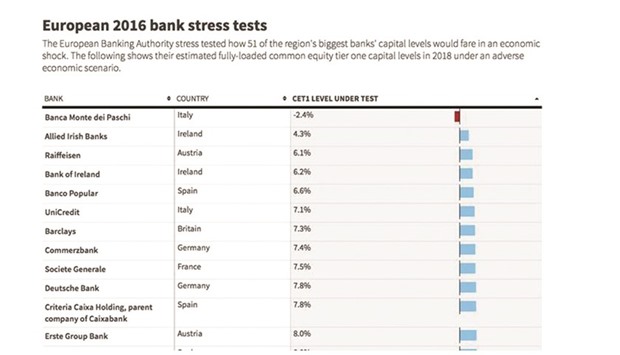

BANK