There is no hero in Tamil cinema, nay Indian cinema, like Rajinikanth whom millions of fans — the largest number surpassing even that of Big B — call with endearing respect Thalaiva (chief).

True to this description, the actor has in recent decades turned into a larger-than-life persona, unbelievably charismatic, yes, but also mysteriously magical — whose performances, though, were caricatured stereotypes. The man on the screen was magnified in image as he was in his deeds. He did the most startling set of tricks that once, long, long ago, began as innocuously as flicking a cigarette in the air and catching it between the lips! There were many other gimmicks he threw at the audiences — who sat spellbound — the awed silences punctuated by hysterical shrieks and whistles.

Rajinikanth, well, was not doing anything new. In the 1940s and the in 1950s, many Hollywood stars had taken refuge in such fascinating feats to get the ticket-paying masses hooked. Humphrey Bogart’s smoke rings which he created with consummate ease enslaved men and women not just to him, but also to tobacco. That Bogart died of cancer, few care to know or even want to.

While Bogart’s obsessive affair with nicotine killed him just 20 days after he had turned 57, Rajinikanth’s excessive gimmickry over the years erased even the memory of his brilliant acting skills. There is a film of his, Mullum Malarum (directed by the legendary G. Mahendran) — where Rajinikanth essays a factory worker, Kali, who after losing his arm in an accident becomes bitter and almost evil.

If there is one work that can go down the annals of movie history as something unforgettable, it is Mullum Malarum. The credit will also have to go to Mahendran, who was bold enough to colour his lead man in shades of grey in a movie that focussed so grippingly on visual realism sans the kind of uncouth melodrama I see in Tamil cinema today.

Perhaps, this is exactly what director Pa. Ranjith must have aimed at when he decided to cut the flab off Kabali to make Rajinikanth less of the mega-hero he had become. Ranjith said in a recent media interview that “whenever a dialogue seemed too cinematic, I would just ask him (Rajinikanth) to tone it down. At one instance he said, ‘Naan nadigane illenga (I’m not an actor at all). Why are you making me do this?’ To which I said, ‘You’re a great actor sir, but you don’t realise it.’”

This is THE point. Tamil producers and directors have been so smitten by the kind of special effects which the medium in its current state-of-the-art avatar affords that they made their heroes into animated forms, robbing them of their very essential human traits. Heroes walk like zombies, all keyed up to take the world with their bare fists. Have you seen how these actors become larger-than-life creatures, throwing away their sickles and shotguns to use their palms to bash villains into pulp? Have you watched the way Surya in Singham II leaps like a lion in the air to come down with his outstretched palm to smash his opponent?

Rajinikanth had done all this and more to just pander to cinema’s obsession with special effects, which let men mutate into monsters — capable of extraordinary feats that no mortal can even dream of achieving.

However, Ranjith’s Kabali intends to change such steeped-in-magic-mantra Rajinikanth into someone all of us can identify with. Rajinikanth’s Kabali — that is his name in the film — plays a man trying to save the oppressed plantation labourers in Malaysia. If one were to go by Ranjith’s words, Rajinikath’s Kabali would do this without resorting to his usual trademark tricks. “I have even made him walk slower,” Ranjith said.

The question here is, will a slower, sober Rajinikanth minus his cocky allure, fortified with almost mystical ability, appeal to his fans? Will they accept him in a form where style will take a backseat, and substance will walk ahead?

I have no clue about this — not as yet, but I did see the other great star in Tamil Nadu, Kamal Hassan, do a fantastic job in Papanasam — where he reprises Mohanlal’s character in Drishyam (Malayalam) as a standard four dropout television cable operator outwitting the cops through the lessons learnt from the endless number of movies he watches.

Papanasam was a critical success that pulled Hassan down from his show-off stuff, like Uttama Villain and Viswaroopam (1 and 2), into Terra-firma, so to say. I quite liked Kamal here, the old Kamal with a strong emphasis on being an actor, sinking into the character, and not on being a magician, lulling audiences into a state of make-believe.

Likewise, Rajinikanth can be a superb artist. He was, at one point. He was discovered by K Balachander, who gave him a small role as an abusive husband (of a character played by Srividya) in the 1975 Apoorva Raagangal. The film explored a controversial subject in the true Balachander tradition, and it got rave reviews. The Hindu wrote: Newcomer Rajinikanth is dignified and impressive.

Rajinikanth’s first pivotal role was in a Telugu movie, Anthuleni Katha, helmed by Balachander — a remake from Tamil, Aval Oru Thodar Kathai, also directed by him. Rajinikanth starred in several wonderful works after that, such as Moodru Moodichu, Avargal, 16 Vayadhinile and Mullum Malarum.

But somewhere along the road, Rajinikanth saw gimmick as the given to bewitch the box office. He did not always succeed. The smoke from his tobacco stick that got his fans on a delirious high, began to suffocate them after a while. His movies began to flop. His last box-office debacle was Lingaa, and the star was ripped apart for this. Not just by critics, but financiers as well.

Ranjith probably saw one in a million chance to re-image the star into an actor — in Kabali. One hopes that Rajinikanth — now well past 60 — would have grabbed this opportunity with both hands and submitted himself to the mandate of the megaphone. After all, he must realise that one can see antics on a circus ring, but a fine piece of performance can emerge only on screen. And Rajinikanth knows that he is perfectly capable of presenting this to us.

Kabali opens in 400 screens in the US alone, and 4,000-plus in India on July 22 — to the clash of cymbals, to the beat of drums, to the anointing of milk on Rajinikanth’s wooden cut-outs and to the sweet smell of incense.

*Gautaman Bhaskaran has been writing on Indian and world cinema for

close to four decades, and may be

e-mailed at [email protected]

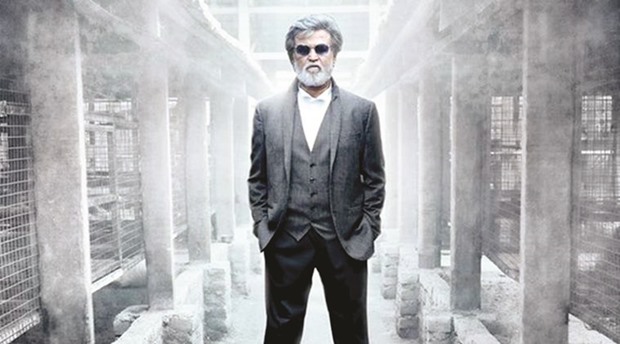

FOCUS ON ACTING: Rajinikanth tones down his on-screen persona in Kabali.