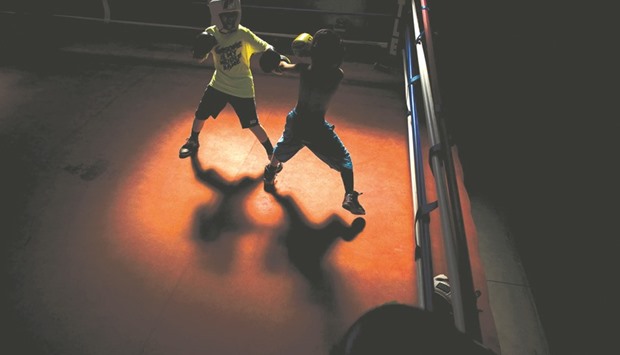

In a nondescript concrete building in Louisville, Kentucky, the smell of sweat hangs in the air as two teens in protective helmets and boxing gloves trade blows at lightning speed, propelled by shouts of encouragement.

Sunshine streams in from a skylight overhead to illuminate the action at the centre of TKO club, where the heirs to Muhammad Ali’s storied legacy are determined to do him proud.

Louisville is the hometown and final resting place of the legendary fighter, who was buried there on June 10 in a send-off befitting the three-time heavyweight champion.

At TKO, teens train in the hopes they might be the next Muhammad Ali.

On any given day, about 80 youths can be found training here, buoyed by the same quest for greatness that spurred Ali – even if they know that boxing legends like him are rare.

“Nobody is close to Muhammad Ali – he is way above everybody else,” said 17-year-old Jeffrey Clancy, a strapping youth naked from the waist up, with a well-defined physique.

“He was so much ahead of his time, it was ridiculous – nobody had really seen fast feet like that in the heavyweight division,” the teenager said.

Jeffrey began boxing 60 years after a young Cassius Clay took up the sport.

The young Louisville upstart came to be known for his way with words, but first he learned to let his fists do the talking in the boxing ring.

Clay started his training in 1954 at the age of 12 – about the same age as many of the kids at TKO - training at a nearby gym that is now part of Spalding University, at a time when Louisville was a segregated city at the crossroads of the Midwest and the Deep South.

He changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and rose to become not just Louisville’s favourite son, but, at the height of his fame, “The Champ” – an American and global phenomenon.

Even after his death, Ali remains a larger-than-life presence, nowhere more so than in the minds of these up-and-coming boxers following in his prodigious footsteps.

Stephanie Malone, 24, a recent boxing recruit, says she has adopted Ali’s credo as her own.

“Be yourself and don’t let anybody dictate who you are, your drive, your determination,” she says, summing up what she said is the crux of Ali’s message.

Malone came to boxing relatively late, but has established herself as one of the most gifted fighters at TKO - bobbing, weaving and jabbing with the best of them, fearlessly taking on a more solidly built opponent who she subdues against the ropes.

The young woman said Ali remains for her an endless source of inspiration.

“I love the way he fought, his head movement, like, ‘I am going to hit you, but you’re not going to hit me’,” said Malone, a youth counsellor by training.

She described the boxing legend as not just a master tactician, but a mesmerizing talent in the ring.

“His footwork was just incredible, it was like he was dancing, like he had a radio inside his head all the time,” she said.

Malone’s young cousin Keilan also trains at TKO, which takes its name from the boxing term technical knockout.

“I didn’t want to hang on the streets and stuff and hang with the wrong people,” he explains, “so I decided to box to keep me off the street.”

Nearby, another youngster, Leslye Harbin, describes the physical catharsis that he gets when he laces up his gloves.

“Boxing will help me with my anger,” he says. “Like, I will take it out on a bag instead of a person.”

TKO founder James Dixon is an African-American man with tattooed arms who first played the role of sparring partner for his son and a handful of other kids in his garage.

Louisville, a city with a storied boxing legacy thanks largely to Ali, had become “the laughing stock of the country” at boxing competitions, he said.

In part, thanks to TKO, for the past few years, that has no longer been the case.

“We’ve got about seven or eight national champions in here,” Dixon says proudly.

“I think it’s due to the spirit of Muhammad Ali and I think it’s due to (his) spirit that we work extremely hard,” he said.

“This is the only city in the world to have four heavyweight champions: Marvin Hart, Muhammad Ali, Jimmy Ellis and Greg Page.” Page 28

Students sparring at the Louisville TKO Boxing Gymnasium in Louisville, Kentucky. The concrete building in Louisville, Kentucky looks like it might once have been a workshop or possibly a warehouse, but it now holds a boxing ring where heirs to Muhammad Ali’s storied legacy are determined to do him proud. A glow of neon and sunshine streaming in from a skylight overhead illuminate the action at the centre of TKO club, where two teens wearing protective helmets and boxing gloves are facing off.