China’s changing of the way it reports its foreign exchange data has brought it into line with international practice but the timing appears to have worsened the market’s appetite for yuan assets.

The data - forex purchase position – measures how much foreign currency is sold or bought by both the central bank and commercial financial institutions. It was replaced with data that captures only the central bank’s forex purchases.

The omission since February fanned growing suspicion that Beijing might be masking the extent of capital outflows amid a slowing economy and currency weakness.

Making matters worse, the People’s Bank of China’s (PBoC) increased intervention in the forwards and swaps markets which sowed more confusion about its currency policy.

“The timing was really bad. The change was made during a time that the yuan faced increasing depreciation pressure and the economy was not faring well,” said Zhang Yiping, analyst at China Merchants Securities in Shenzhen.

Investors were also concerned about China’s falling reserves and that it would have a hard time shoring up the yuan.

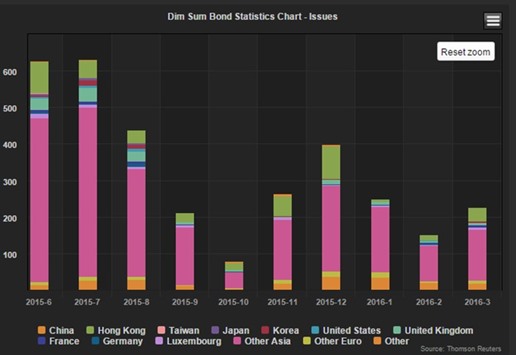

Demand for yuan-denominated assets have fallen since the start of the year, with volumes in the dim sum bond markets plummeting.

Investors have dumped Chinese stocks since last June, while the yuan has been under depreciation pressure in the second half of 2015.

Xu Gao, chief macroeconomic analyst at Everbright Securities, said a lag between the publication of forex purchases and foreign reserves data meant analysts had looked to FX purchases as a leading indicator of outbound flows. A rise in FX purchases points to inflows, and a fall, to outflows.

That role took on greater significance last year as the exchange rate softened and Chinese businesses rushed to repay their dollar-denominated liabilities.

In December - the last month in which the FX purchase data was reported - Chinese banks sold a net 568.3bn yuan ($86.4bn) worth of foreign exchange, nearly double November’s net sales - followed by a sharp drop of $99.5bn in the country’s foreign exchange reserves in January , the second-largest monthly drop on record.

The decision to halt publishing the combined forex purchase and sales position data came shortly afterwards, and it was implemented without notice: it disappeared from reports and was replaced by a line showing central bank net purchases.

Some analysts suspected the omission helped Beijing conceal the role Chinese commercial banks were playing in buying yuan to support the PBoC.

“Honestly, given that these days commercial banks possess an ever-increasing amount of foreign exchange, the omission could obscure the ‘firewall’ role played by state banks in the forex market,” said an economist at a Chinese securities brokerage who declined to be named due to the sensitive subject.

The PBoC and others justified the change by saying the data was statistically problematic. It overlaps with other data and, in some cases, allows for double counting of commercial foreign exchange assets.

The reshuffle of the composition of foreign exchange data, however, brings the PBoC into line with international practice.

“The PBoC’s forex assets data is more representative,” said Huang Yi, head of forex trading at Guangfa Bank in Shanghai.

But despite the PBoC’s stated intentions to let market forces play a greater role in pricing, onshore and offshore exchange rates have been tightly controlled in recent weeks. The traded rates have closely followed the official guidance rate since mid-February.

“In the past few months, the PBoC intervened intensively to prevent a fast depreciation of CNY, and many believe that they have also stepped into the FX forward market,” noted Zhou Hao, senior emerging markets economist at Commerzbank in Singapore.

Analysts say that may explain how Beijing managed to stabilise the exchange rate while at the same time slowing the drain on its forex reserves.

..