The head of the Swedish Bankers Association has expressed concern that Basel is being fed a message that doesn’t represent the position of regulators or banks in his country.

The disagreement is over the leverage ratio: how much capital a bank should hold as a percentage of total, unweighted assets. The Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority doesn’t want a high ratio, arguing it would take away the freedom to set capital based on risk. Bankers agree.

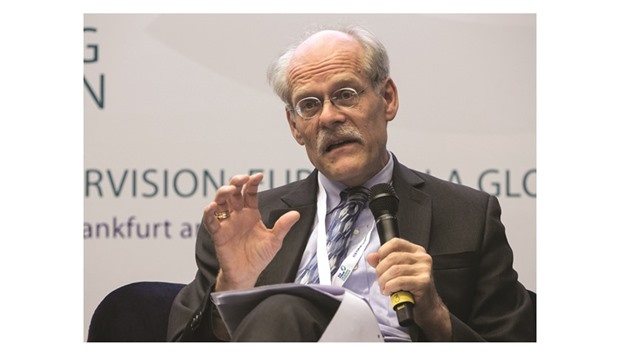

But the governor of Sweden’s central bank, Stefan Ingves, has signalled he wants a stronger backstop to prevent lenders basing capital ratios on optimistic interpretations of their balance sheets. Ingves also happens to be the chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which sets the framework for regulation globally.

“When I talk to people in Basel and Brussels, I hear that there are a few countries that are totally against the risk-based view,” Hans Lindberg, the head of the Swedish Bankers Association, told Bloomberg. “They mention the US, India, to a certain extent Switzerland, and then they mention Sweden. But that’s not the official Swedish view, the view of the government or the FSA.”

European regulators will recommend a level later this year. Basel said in January that the ratio should be set at a minimum of 3%.

Sweden’s biggest banks have a leverage ratio of just over 4%, under Basel III rules, while common equity Tier 1 capital as a percentage of total, unweighted assets hovers just below that — and “has been largely unchanged over the last few years,” Ingves said in a November speech.

Improvements in Swedish banks’ risk-weighted capital ratios — touted as some of Europe’s highest — have been largely achieved by leaning on risk models, Ingves says.

Sweden’s FSA acknowledges that internal risk models can be improved - it raised risk-weight requirements for corporate assets this month - but it also argues that a binding ratio may ultimately add risk because it lacks nuance.

The tension between the FSA and the Riksbank follows an earlier battle in which the two institutions fought over who gets the final word on macro-prudential oversight.

Ingves had argued that the Riksbank was better placed to provide a holistic approach. In the end, parliament gave full oversight powers to the FSA. But outside Sweden, the turf war continues.

“It seems like it’s the Riksbank’s view that’s seen as the Swedish position in Basel,” Lindberg said. “That’s unfortunate, as it’s the FSA that’s responsible for supervision of banks here in Sweden.” Martin Floden, one of five deputy governors at the Riksbank, says it’s now “very clear” that the FSA “decides regulatory issues.”

“But the Riksbank also has a task to safeguard and secure an effective system of payments, and that includes looking at financial stability,” he said. “So we have a role when it comes to analysing and having opinions on the development of the financial market.”

FSA Director-General Erik Thedeen wrote a letter to the Riksbank addressing the communications glitches that have occurred. He says the division of labour is “crystal clear.”

“You just need to read the law: it’s us,” Thedeen said.

Stefan Ingves, governor of the Riskbank, Sweden’s central bank, and chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, speaks during a banking supervision forum at the ECB headquarters in Frankfurt. Ingves has signalled he wants a stronger backstop to prevent lenders basing capital ratios on optimistic interpretations of their balance sheets.