The Bank of England won’t raise rates until early 2017, economists polled by Reuters said, pushing back expectations for the third time this year, which would mean eight years of record-low borrowing costs.

Many of the economists polled this week said all bets on where rates were headed would be off if Britain votes on June 23 to leave the European Union.

Since the start of the year, the median forecast in Reuters polls has moved three times. In a Jan. 4 poll economists thought the first hike would be in April-June but the latest survey said it would be the first quarter of next year before rates rise.

However, the latest change was a close call, with just under half the economists expecting a fourth quarter or earlier move and a little over half a delay until at least 2017.

“We have pushed back our main scenario for the first rate rise to early 2017 due to evidence from recent PMI surveys and other data that slower global growth, and uncertainty relating to the EU referendum, may be beginning to take the edge off the UK recovery,” said John Hawksworth at PwC.

Bank Rate has sat at a record low of 0.5% for seven years. None of the 59 economists polled expect any move when the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee meets on March 17.

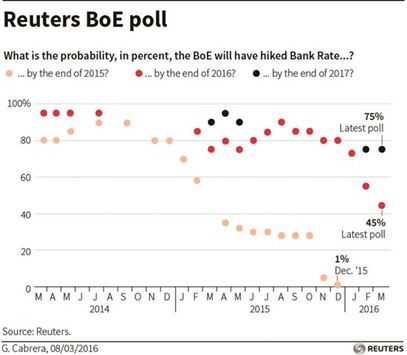

The poll found there is only a median 45% chance of a rate rise by the end of this year — down from 55% in a Jan. 26 poll — but a more convincing 75% likelihood of a shift by the end of next year. Money markets, which can only really give a solid guide over a two-year horizon, are not pricing any hike for four years.

When the Bank does start to tighten policy, it will be in no hurry, the poll found. By the end of next year Bank Rate will be at 1.25% and then nudge up to end 2018 at 1.75%.

The BoE was once expected to be the first major central bank to tighten policy but the US Federal Reserve took that crown when it raised rates in December. But fears of another global economic slowdown have tempered expectations for further tightening there.

Those worries, alongside non-existent inflation, mean the European Central Bank as well as the People’s Bank of China are instead widely predicted to ease policy.

Also muddying the waters, Britons will vote on June 23 on whether to tear up their EU membership card. If they do, the country’s economy would be worse off, nearly all foreign exchange strategists and economists polled by Reuters said.

“The issue of when the UK raises rates depends to a large degree on (one) global events and (two) the outcome of the Brexit referendum. Therefore any attempt to predict when rates might rise is highly conditional upon events elsewhere,” said Peter Dixon at Commerzbank.

Opinion polls have been close but the “In” campaign has mostly been showing a slight lead.

Taking its first concrete step to keep markets running smoothly, the BoE said on Monday it would offer extra funds to banks as the vote nears.

Governor Mark Carney said yesterday the BoE was not taking a view on the long-term implications for Britain’s economy of a so-called Brexit but warned an “Out” win could hurt economic activity in the short term.

..