After a long wait for inflation to accelerate, US Federal Reserve officials face a complex and possibly divisive debate over whether recent evidence of rising prices is strong enough to move ahead with planned rate hikes.

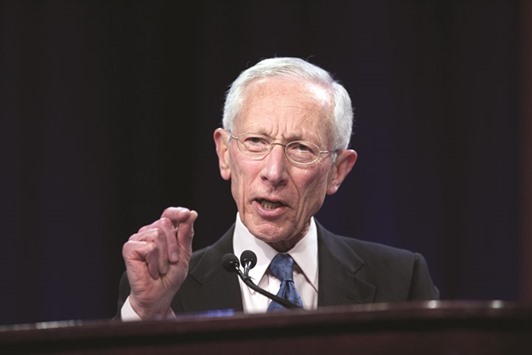

In separate statements yesterday, policymakers at the core of that debate staked out starkly different views, with Fed vice-chairman Stanley Fischer saying economic data now points to the “first stirrings” of inflation, and Fed Governor Lael Brainard countering that the Fed should not move until inflation proves its “persistence.”

The differing views may not matter immediately, when the Fed meets next week.

A rate hike at that meeting is not expected after weeks in which oil prices have remained depressed and global equity markets have been volatile.

But it could tax Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s ability to maintain consensus over the year as the Fed decides whether it is riskier to let inflation rise more quickly now, and try to control it later, or raise rates more slowly in a weak world economic environment.

That discussion, largely moot over an extended period in which the Fed persistently missed its 2% inflation target, may be joined in full after the central bank’s preferred measure of inflation rose to 1.7% in January.

“We’re not that far away” from an inflation target that has been elusive in an era of cheap oil, weak global demand and a strong US dollar that has held down the cost of imports, Fischer said.

Fed officials have argued since mid-2014 that those inflation “headwinds” would pass, and recent data on prices of goods and services, as well as a jump in commodity prices, may indicate that time has finally come.

“We may well at present be seeing the first stirrings of an increase in the inflation rate,” Fischer said, adding that an increase from too-low levels is “something that we would like to happen.”

Investors who had largely priced out a further Fed rate hike until late this year have pushed those expectations forward in recent days, as oil has rallied and prices of some other commodities crept higher.

It may take more than that to convince Fed members like Brainard. In recent weeks even policymakers who had been among the more concerned about inflation joined her in worrying that public expectations about inflation were falling, often a precursor to even weaker price increases and possible deflation.

Brainard, the leading voice for the Fed to stay cautious in a world where China remains a risk and growth overall is slow, said one strong month is no reason to rush.

While January’s data was good, “it’s just that — a data point... For me... I want to see a pattern, some persistence. That would give me some comfort,” she said.

“Given weak and decelerating foreign demand, it is critical to carefully protect and preserve the progress we have made here at home through prudent adjustments to the policy path,” she told a group of bankers.

The Fed in December raised interest rates for the first time in nearly a decade. At the time, it signalled it would likely raise rates four more times this year, reflecting a stronger US labour market and the view that inflation will begin to rise toward the Fed’s 2% goal.

But an oil price slump, a global economic slowdown and volatile financial markets since the beginning of this year have convinced investors that the Fed’s optimism may be misplaced.

Wall Street economists now expect just two rates hikes this year, and traders of interest-rate futures are betting there will be just one.

Fed vice-chairman Stanley Fischer speaks at the Economic Club of New York (file). In separate statements yesterday, policymakers at the core of a debate staked out starkly different views, with Fischer saying economic data now points to the u201cfirst stirringsu201d of inflation, and Fed governor Lael Brainard countering that the Fed should not move until inflation proves its u201cpersistence.u201d