Global aluminium production fell by 1.6% in January. It doesn’t sound like much but it was the first year-on-year decline since October 2009.

Good news for a market that has for years been struggling with chronic over-production and low prices.

Even better news that production in China also fell for the second consecutive month with the year-on-year decline accelerating to 4.5%.

China accounts for over half the world’s output of the light metal and has been pumping out surplus units in the form of semi-manufactured product exports.

Or, “dumping” surplus units on the rest of the world, if you believe US producer Century Aluminum, which is leading an increasingly bellicose campaign against what it and other US players claim is an existential threat caused by unfair Chinese subsidies to its producers.

Maybe, at long last, even China is starting to rein in its own chronic over-production? That’s what the latest monthly figures published by the International Aluminium Institute (IAI) suggest.

But here’s the catch. What if the figures are wrong?

Or, rather, what if the Chinese figures supplied to the IAI by China’s Nonferrous Metals Industry Association (CNIA) are wrong? Because they’ve been wrong in the past. And wrong in a big way, as we’ve just found out.

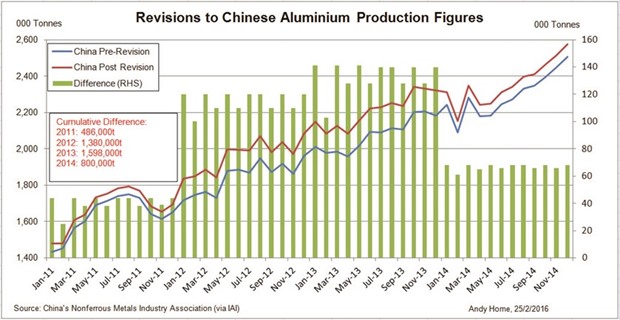

The Chinese have just revised their historical production figures for 2011-2014 by a massive fourmn tonnes.

Analysts have always been a little wary about the Chinese component of the IAI’s monthly production bulletin.

In particular, the figures around the beginning of any year, both Western calendar and Lunar, have been prone to fairly wild fluctuations.

And that’s been true this year as well. Chinese annualised production dropped by a massive 2.84mn tonnes in December.

Often as not the figures jump again after the Chinese holidays and analysts tend to view this annual anomaly as a case of delayed reporting by individual Chinese smelters.

This smoothes out the trend and it’s the trend that counts, right? After all, aluminium production figures tend to be more reliable than those for other metals.

Unlike the host of smaller mines operating in China, some of them little more than family-run businesses, aluminium smelters are pretty hard to miss. They are big, really big, particularly since Beijing forced the phase out of smaller-capacity plants several years ago.

True, there have been nagging doubts as to whether CNIA’s data was capturing all the country’s production facilities. But just to be on the safe side, the IAI and CNIA included an “unreported” column in the Chinese figures. The IAI does the same for its figures for the rest of the world to capture those producers not directly submitting production figures.

And that statistical Chinese safety net was a large one, equivalent to 3mn tonnes of “unreported” production in 2013.

It disappeared at the start of 2014 and the “official” figures jumped correspondingly, suggesting that missing smelters had been tracked down and incorporated into the figures.

The latest revisions, however, suggest that it’s only now that those smelters have supplied historical data. And it turns out they were producing far more than allowed for by that safety net.

The resulting revisions amount to 486,000 tonnes in 2011, 1,380,000 tonnes in 2012, 1,598,000 tonnes in 2013 and 800,000 tonnes in 2014.

Paul Adkins of specialist consultancy AZ China, who has in the past flagged up discrepancies in the Chinese data, pins the revisions on one producer in particular.

“We know that Hongqiao was the largest culprit for the missing tonnage, and they got incorporated at the start of last year.”

Of the 2011-2014 revisions, he goes on to explain; “it’s clearly one or two smelters’ worth per month, with one plant having been added in at the start of last year, which again points to Hongqiao, as they have four smelters in total.”

Does any of this statistical nit-picking matter? After all, it’s all in the past and it’s the present that matters.

The problem, though, is that you don’t know where you’re heading if you don’t know where you’ve come from, especially when it comes to calculating historical market surplus and resulting stocks build.

This is particularly true of the aluminium market. Uniquely, among the big base metal markets, there is no independent statistical body doing the hard number-crunching work for the rest of us.

*Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The opinions expressed are his own.

..