Crouched in the shade beside a mud hut near her parched wheat fields in central India, Harkiya is getting desperate.

India’s first back-to-back droughts in three decades left the 47-year-old single mother with no income. She lives on money borrowed from relatives, and has no cash to take her sick daughter to the hospital - all the more worrying because her husband and son died from a mysterious illness last year.

“Somehow we are alive,” Harkiya, who goes by one name, said in her village in Madhya Pradesh state. “I need any work to survive. But here there is no government work.”

During previous droughts, Harkiya relied on the world’s biggest public works programme to earn cash doing menial tasks like digging ditches, building roads and planting trees. Yet this year, local officials say the central government isn’t providing enough money to fund work projects.

Rising discontent in rural India is pressuring Prime Minister Narendra Modi to spend more on the $5bn jobs programme in his budget on February 29. His party got crushed in India’s third most-populous state in November, and faces as many as nine state assembly elections in the coming fiscal year that will affect his economic agenda until the next national vote in 2019.

Modi “neglected the countryside” with an emphasis on urban development in his first two years, said S Mahendra Dev, director of the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research in Mumbai. “They should make bold moves in the budget focusing on rural India - otherwise they will pay a heavy political price.”

Modi has already started turning his attention to the hinterlands. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley this month said the government would spend a record amount on the rural jobs programme in the current fiscal year and revive it with more productive projects. Planned improvements include faster payments to states, direct deposits to beneficiaries and more guaranteed work days.

“When there was a change of government in 2014, there was talk in and outside parliament on whether the scheme will be discontinued or its fund allocation will be curtailed,” Jaitley said. “But the new government not only took forward the scheme but also increased its allocation.”

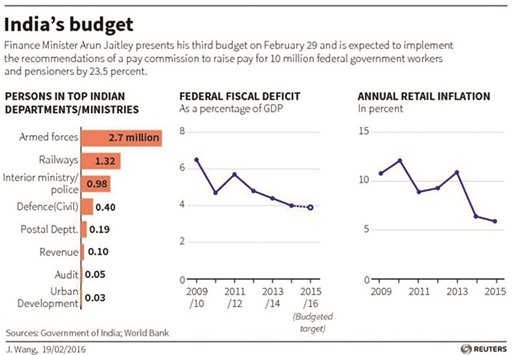

The demands for more rural support, combined with proposed salary increases for government employees, risk derailing Modi’s fiscal consolidation plans. A Bloomberg survey of economists expect next year’s budget deficit at 3.6% of gross domestic product, wider than the target his government set last year.

India’s villages, home to about 70% of the nation’s 1.3bn people, aren’t feeling its world-beating 7.3% economic expansion. Rural wage growth is falling, food exports are down and production of mass-market goods has dropped.

In times of distress, farmers don’t have many places to turn. While subsidized food ensures nobody starves to death, other forms of welfare are lacking: Health care is spotty, crop insurance is inadequate and emergency relief can take months to arrive.

With most government handouts targeted at vulnerable groups like the elderly or widows, the rural jobs programme is effectively the only cash transfer programme available to all villagers. Known as MGNREGA, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act began in 2006 under the previous Congress-led government. It mandates 100 days of wages per year to rural households covering some 277mn workers - more than the population of Brazil.

The programme “is good policy weakly implemented,” said Sabina Dewan, president and executive director of JustJobs Network, a research group focused on job creation. “The scheme has the potential to provide broad-based income support to the poorest, but its potential has not been realised.”

It’s supposed to work like this: Local authorities receive money from the central government to implement projects ranging from flood management to drought proofing. Villagers then apply for work. If no job comes within 15 days, they receive an unemployment allowance. Wages as high as 251 rupees ($3.66) a day must be paid within two weeks.

In many places, however, the central government fails to provide enough funds, and local authorities are slow to develop projects. Village leaders determine who gets work. When jobs do come, wages can be delayed for months. Corruption is rampant.

After Modi took power, he ridiculed the programme as a “living monument” to the failures of the ousted Congress party. It deteriorated during his first year in office.

The number of total work days declined about 25% in the year through March 2015 from 2.2bn. The average days of employment also dropped in that time, and actual spending fell 6% to 360bn rupees ($5.2bn).

The political fight in New Delhi affected places like drought-hammered Bundelkhand. Vast stretches of barren land mark the area on the border of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state.

Signs of distress are everywhere. Houses in some places are locked and shuttered after residents left in search of work. One municipality hired armed guards to stop thieves stealing water from a reservoir.

As of early February, Harkiya had yet to receive compensation for destroyed crops or a 200-rupee-a-month widow pension. She already spent the 20,000 rupees she received following her husband’s death.

In 2008, Harkiya’s family found work digging a well through the jobs programme. These days, though, nothing much is available due to a lack of funds from New Delhi, according to Monalal Kumhar, a local elected official who represents Harkiya’s village. Siddha Gopal Verma, who supervises the rural jobs programme in that part of Madhya Pradesh, said delays in wages and work programmes are common.

Modi’s government is working to end the “chronic” problem of late disbursals, according to Aparajita Sarangi, a joint secretary in the Rural Development Ministry who oversees the jobs programme. She vowed to look into the cash shortages in Bundelkhand.

“If they want more funds, we will give them in the first week of March,” Sarangi said, adding that Modi may boost MGNREGA funding by 4% to 385bn rupees in the next fiscal year. “The government has been extremely generous for this programme.”

After his early criticism, Modi did a U-turn on MGNREGA despite its flaws. He had little choice: Investments in rural roads and irrigation take time to pay political dividends, and efforts to develop less wasteful social welfare programmes are still in nascent stages - including a revamped crop insurance policy that Modi trumpeted on Sunday.

“Even though this right-based programme is marred by poor performance and rampant misuse, it has become the only hope for many for survival,” said Jagmohan Singh, an activist with Akhil Bharatiya Samaj Sewa Sansthan, a group that supports marginalised people in Bundelkhand.

Throughout the region, residents just want a job. Gayadeen Adivasi can’t provide his 10-member family with enough food despite having four acres of farmland. He relies on 2,000 rupees ($29) a month that his son sends home from earnings as a day labourer in Delhi.

“Being a farmer here is a curse,” Adivasi said next to a dried-up well as cows scoured the dusty fields for food. “We will die unless we get some work.”

KRISHNAN