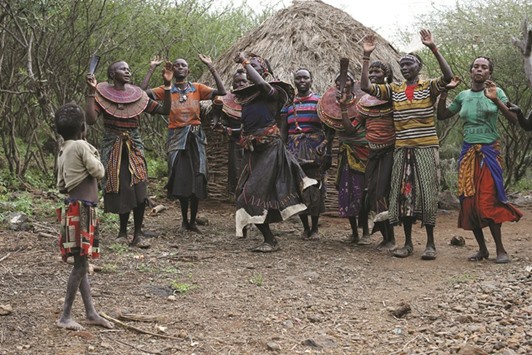

Pokot women dance in celebration the day before an initiation ceremony for young men in Baringo County, Kenya.

In an isolated region in Kenya’s Rift Valley, young men spear a bull in a ceremony that marks a gateway to adulthood.

Far from the bustling capital of Nairobi, locals gather at dawn, men on one side, women on another, to witness the event in a community where cattle play a central part in life.

The men, aged between 18 and 20, are part of a small Pokot community of herdsmen who tend cows, goats, sheep, camels and donkeys in Baringo County.

The initiation is called Sapana in the Pokot language.

“In our culture, Sapana is the most important rite for a man to be able to gain authority within his community,” says Hassan Tepa, an elder.

It is a jolting, three-hour drive to this region from the lowland town of Marigat, close to Lake Baringo. Kenya has about 620,000 Pokots, the 2009 census statistics show, and some also live in neighbouring Uganda’s Karamoja region.

As Kenya develops and more people migrate to the cities in search of work, such traditional practices are on the wane.

However in this remote region, ceremonies such as Sapana still hold sway.

The ritual allows men to sit with local elders and take part in their community’s decision-making.

Sapana also gives improved access to marriage, once the man and his family have accumulated a dowry of cattle.

A man as old as 30 can also undergo the rite. The initiate’s age depends in part on when he and his family can afford to spare a bull for the killing in a community where cattle are precious.

The Pokots can have several wives, and men are allowed to marry women many years their junior.

Livestock are everything for the Pokots, representing wealth and social status. And in an isolated region with no permanent police presence, elders deal with disputes.

Those who have broken the law are often required to pay a fine in the form of animals.

The Sapana ceremony begins the day before, usually at dusk, when locals gather and fires are lit for the night. Then begins the dancing, singing and drinking of fermented local wine. Many stay awake through the night.

The young men stay at home, waiting for the morning’s initiation rite.

As the sun rises, the young man walks towards the bull, fixes his aim and pierces the animal with a spear on its right side.

According to tradition, the bull must be speared several times before death as a way to respect its life - to consider that a single blow could fell a bull would be to dishonour the animal.

Village men open up the slaughtered animal, taking it in turns to eat clots of blood. Most of the blood is kept in a container to be mixed later with milk, a traditional delicacy to be shared.

Men take their place in a semi-circle and wait for the choicest parts of the animal to be cooked and served to them. Women and children await their turn at a distance. Every single part of the animal is eaten or put to use.

In one of the most important, final stages of the ceremony, a respected elder smears the contents of the animal’s stomach on the initiate.

As Tepa explains, this concluding rite seals the young man’s entrance to adulthood, conferring a new status on him.

“Only then will he be able to speak to elders,” he says. “In return (he will) be listened to and respected.”