One person has been left brain dead and five others have been hospitalised after taking part in a clinical trial in France of an experimental drug made by Portuguese drug company Bial, French Health Minister Marisol Touraine said yesterday.

In total, 90 people have taken part in the trial, taking some dosage of the drug aimed at tackling mood and anxiety issues, as well as movement co-ordination disorders linked to neurological issues, Touraine said.

The six men aged 28 to 49 had been in good health until taking the oral medication at the Biotrial private facility that specialises in clinical trials, she said.

“This is unprecedented,” Touraine told a news conference after meeting volunteers and their families in Rennes, western France. “We’ll do everything to understand what happened.”

Prosecutors have opened an investigation into the case.

The six men started taking the drug on January 7.

The brain-dead volunteer was admitted to hospital on Monday, minister Touraine said.

For three of the five others – who went in on Wednesday and Thursday – there are fears of irreversible handicap, doctor Gilles Edan said, though he still hoped that would not be the case.

One of the six had no symptoms but was being carefully monitored, he said.

Testing had already been carried out on animals, including chimpanzees, starting in July, Touraine said.

All trials on the drug have now been suspended and all volunteers who have taken part in the trial are being called back, the health ministry added.

The medicine involved is a so-called FAAH inhibitor that works by targeting the body’s endocannabinoid system, which is also responsible for the human response to cannabis.

Bial said in a statement that it was committed to ensuring the wellbeing of test participants and was working with authorities to discover the cause of the injuries, adding that the clinical trial have been approved by French regulators.

The company said five people, rather than six, had been hospitalised, including one left brain dead, without explaining the discrepancy with the official French figures.

Bial insisted yesterday that it had followed “international best practice” in the drugs trial.

The company said in a statement it had followed “the applicable legislation” and that it would co-operate with the investigation underway to “determine in a rigorous and exhaustive manner” what happened.

“Our principal concern, at the moment, is taking care of participants in the trial,” Bial said, particularly those who have been hospitalised.

The manufacturer said the product was an “inhibitor of the enzyme FAAH”, or fatty acid amide hydrolase, which was being developed with “respect since the start for international best practice, with pre-clinical trials carried out, notably with respect to toxicology”.

“This trial was approved by the regulatory authorities and the French ethics committee,” the company said, adding: “108 volunteers in good health participated in the testing of this new molecule without developing any adverse reaction, either moderate or serious.”

There was no explanation as to the discrepancy in this number – 108 – and the number given by minister Touraine.

Based in northern Portugal near the town of Porto, Bial says on its website that it is the country’s largest pharmaceutical company, founded in 1924 with a presence in 58 countries.

It has produced treatments for a range of ailments including problems with the nervous system and cardiovascular health, as well as antibiotics and anti-allergens.

The drug test in France has been carried out since the summer by Biotrial, a medical research company approved by the health ministry, on behalf of the Portuguese company.

Cases of early-stage clinical trials going badly wrong are rare but not unheard of.

In 2006, six healthy volunteers given an experimental drug in London ended up in intensive care.

One was described as looking like “the elephant man” after his head ballooned. Another lost his fingertips and toes.

In the initial Phase I stage of clinical testing, a drug is given to healthy volunteers to see how it is handled by the body and what is the right dose to give to patients.

“Undertaking Phase 1 studies is highly specialist work,” said Daniel Hawcutt, a lecturer in clinical pharmacology at Britain’s University of Liverpool.

Medicines then go into larger Phase II and Phase III trials to assess their effectiveness and safety before they are finally approved for sale.

Europe has strict regulations governing the conduct of clinical trials, with Phase I tests subject to particular scrutiny.

But Ben Whalley, a professor of neuropharmacology at the University of Reading, said these could only minimise risks, not abolish them.

“There is an inherent risk in exposing people to any new compound,” he said.

The 2006 London trial led to the collapse of Germany’s TeGenero, the company developing a medicine known as TGN1412.

The drug has since gone back into tests for rheumatoid arthritis and is showing promise when given at a fraction of the original dose.

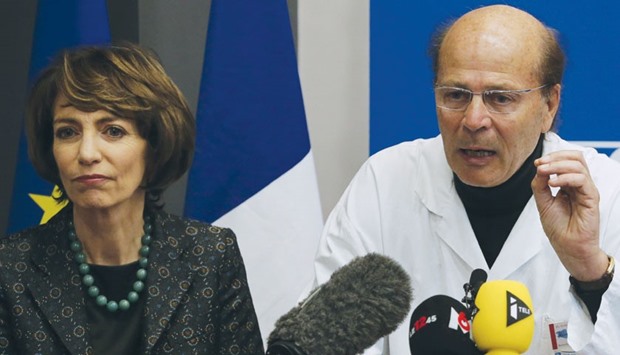

Minister Touraine listens as Gilles Hedan, professor of clinical neurology, explains at a news conference in Rennes, France on the case of the clinical trial that has left one person brain dead and five others are in a serious condition.