German Bunds were set to end their most volatile year since 2011 with yields higher than at the end of 2014 after a failed bid to break below zero raised questions about their safe-haven status and showed the limitations of ultra-easy monetary policy.

Yesterday, the last trading day of 2015, 10-year Bund yields, the benchmark for eurozone borrowing costs, were up 1 basis point (bps) on the day and about 10 bps on the year at 0.64%. In 2014, they fell almost 150 bps.

The dramatic rise of Bund yields from a record low of 0.05% in mid-April to above 1% in early June raised concerns about thin market activity as tighter regulation strained banks’ market-making abilities.

During that period, one of the world’s safest assets turned into one of the riskiest. Investing in Bunds for their safety is no longer a straightforward bet.

Thin market conditions are set to remain in place in the coming year and be further exacerbated by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) €60bn a month asset-buying programme, which is set to run at least until March 2017.

In April, the view that ECB purchases would push yields into negative territory was challenged by one of the rare instances in which monthly inflation data beat expectations.

Thin liquidity and the market’s one-sided positioning – bets that Bund yields would fall further were almost unanimous – meant that once the sell-off started it snowballed.

With coupons near zero there was no protection for investors and their losses went into double digits.

Inflation then resumed its disappointing trend but the fresh memory of those losses prevented a new test of zero yields.

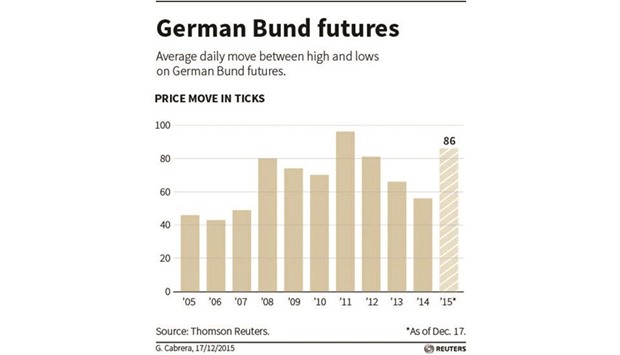

“That massive rise of yields coming out of nowhere was certainly the most significant event of the year for Bunds,” DZ Bank rate strategist Christian Lenk said. “This kind of spikes are going to be the new normal.” The average daily move between the highest and lowest price for German Bund futures was the highest since 2011, Thomson Reuters data shows.

In other markets, Greece had another rollercoaster year with 10-year yields trading between a low of just under 7% last month and a high of almost 20% in July, when fears of a eurozone exit climaxed during bailout talks between the new Syriza-led government and its international creditors.

A third bailout has since been agreed, Syriza was re-elected with a radically different mandate to implement new austerity measures and yields were last at 8.27%, more than 100 bps lower than at the end of 2014.

Most other eurozone bond yields hit record lows in April-May. Spain and Italy, which were at the heart of the financial crisis in 2011-2012 when their bond yields surged to unaffordable levels above 7%, are now borrowing at well below 2% for 10 years.

Eurozone markets, protected by ECB buying, have taken inconclusive election results in Portugal and Spain as well as a stronger push for independence in Catalonia in their stride.

The worst performing market in terms of returns was Finland, which saw a steady deterioration in its economic outlook and a recession in its largest trading partner Russia. Perhaps surprisingly, the best one was Greece.

Italy held the last auction of the year, selling €6bn – the top of the planned range – in five-year and 10-year fixed rate bonds as well as seven-year floating rate paper.

GER