By Arno Maierbrugger

Gulf Times Correspondent

Bangkok

Myanmar’s opium production remained at an output of estimated 647 tonnes in 2015, a new report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) released on December 15 in Bangkok said, noting that production was stable since three years despite a reformist government having spurred solid economic growth in a country where poppy cultivation is large connected to rural poverty.

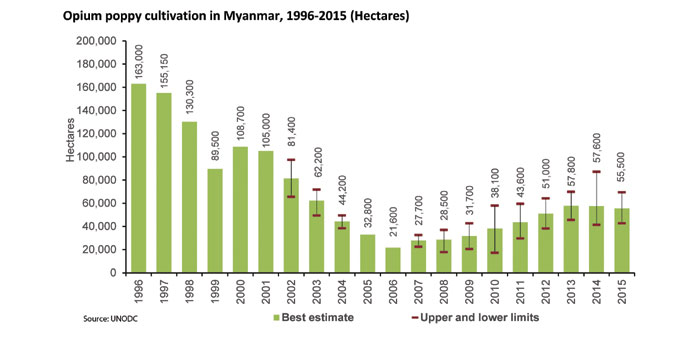

Myanmar remains second in annual opium production behind Afghanistan and ahead of Mexico, Turkey and Laos. Despite actions undertaken to eradicate poppy fields, the total area under opium poppy cultivation stood more or less unchanged at 55,500 hectares in 2015, the UNODC said. Main production areas are Chin State, Kachin State, northern and southern Shan State and Kayah State in the mountainous north and east of the country.

The main export country for Myanmar opium is China, to where around 70% of the drug or its derivate, heroin, are smuggled with the involvement of a wide network of stakeholders in the opium business, including local police, village administrators and members of the ethnic armed groups in their respective areas, as well as Myanmar and Chinese border officials. One year’s income from this trade for Myanmar ranges in the billions of dollars but can, due to the opaque character of the trade, only be estimated.

While farmers in Myanmar receive around $350 for one kilogramme of raw opium, wholesale prices at the end of the trade chain easily exceed $3,000 – which brings the value of a year’s harvest to around $2bn –, ten-fold in case the opium has been processed to heroin, according to UNODC data.

Opium and illicit drugs derived from it are also widely available and cheap within Myanmar, where they account for serious social and health problems among the population, mainly mining labourers, farmers and students, with police tending to turn a blind eye.

The lawless situation makes it difficult for the government and non-governmental organisations alike to address the issue. It is acknowledged that poverty is at the root of the problem of growing illicit crop, but the farmers insist they are doing “nothing criminal”.

In a joint statement by the Myanmar Opium Farmers’ Forum, so to say the professional body of the poppy farmers in Myanmar, released by the Netherlands-based social think tank Transnational Institute (TNI) on December 14, the farmers say that they grow opium “to ensure food security for their families and to provide for basic needs, and to have access to health and education.” According to the report, “the large majority of opium farmers is not rich and grows it for their survival. Therefore, they should not be treated as criminals.”The farmers also insist they “know nothing” about where the opium goes once it leaves the fields, saying that “they have nothing to do with the traders.” They, however, acknowledge that opium is causing “many problems related to drug use, especially heroin, in their families and society.”

Another problem is that poppy growing takes away much-needed land to satisfy normal food needs. The reports say that villagers in opium-growing areas use large parts of income from opium for purchasing food and are forced to buy expensive rice from other parts of the country or from imports.

Tom Kramer, the coordinator of TNI’s Drugs Democracy Programme in Myanmar, said that “the main reason people grow opium is poverty. They should be involved in decision-making processes about drug policies and development programmes that are affecting their lives.”

This is easier said than done. The UNODC notes that opium poppies are by far the most lucrative crop for farmers, with a single hectare able to generate $4,600 in income in Myanmar – about 13 times of what a hectare of rice could. This makes it difficult to convince farmers to switch to other relatively high-yielding crops such as coffee or grapes.

Legal use to produce pharmaceuticals from opium such as painkillers could be a solution to convert poppy growing into a beneficial and legal business. Cultivating opium for pharmaceutical purposes has been successful in Australia (Tasmania), France, India, Spain and Turkey, among other nations. However, without a stable legal framework of legal opium production and international supervision, a decriminalisation of opium farming and trading remains a very big task for Myanmar and certainly can’t be fixed in a short time.

And even the new Myanmar government led by democracy fighter Aung San Suu Kyi will have a hard time to break up a system well-interlocked across local authorities, border officials and army brass since decades.