Bloomberg

Riyadh

Its reserves sapped by more than a year of cheap oil, Saudi Arabia is expected to cut spending when it unveils its budget this month, while steering clear of the more painful reforms some economists argue are needed to ensure long- term financial stability.

The 2016 plan will be the first under King Salman and an economic council led by his son. It follows a year in which a collapse in oil prices pushed the world’s largest crude exporter to spend down reserves and issue bonds for the first time since 2007.

Next year “is going to be a tough year for Saudi,” John Sfakianakis, a Riyadh-based Middle East director at Ashmore Group, said by phone. If the budget “doesn’t create a buzz and confidence,” business sentiment could soon turn negative, he said.

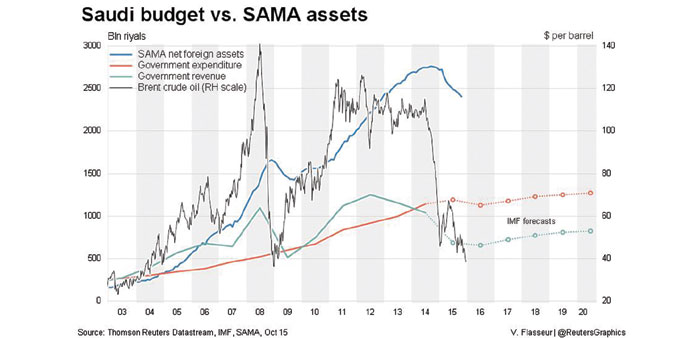

The hit to its prime source of revenue means Saudi Arabia is on course to record a fiscal deficit equal to 20% of economic output this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. A Bloomberg survey of eight economists forecasts it will narrow to 14% in 2016. Without measures to shore up public finances, the nation could exhaust assets that support spending within five years, the IMF warned in October.

Budget planners held overall spending steady last year but economists now expect a change in direction: substantial cuts to project outlays, a tighter rein on ministry running costs and searches for new forms of income.

“The budget will likely be the first stage of a multi-year fiscal readjustment programme,” said Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank. “It’s not going to just be on the spending side, but also on the revenue side.”

The fiscal crunch has pushed the government to mull putting projects on hold, sell bonds and order departments to search for savings. Major development initiatives won’t be delayed, Finance Minister Ibrahim al-Assaf said earlier this year, signalling projects like the Riyadh metro system are unlikely to be affected.

Still, the budget is likely to cut capital spending by about 10%, said Fahad Alturki, Riyadh-based chief economist at Jadwa Investment. Current expenditure, about half of it allotted for public-sector wages, will probably rise though at a slower rate than in the past, he said.

Measures like the $30bn King Salman handed out in salary bonuses and infrastructure spending early in his reign won’t be repeated, analysts said.

Less clear is whether major policy reforms - such as the privatisation of government companies, new forms of taxation or changes to energy subsidies - will feature. In an interview with the New York Times, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman said the government planned to raise domestic energy prices, and privatise and tax mining, without saying when.

Energy subsidies that benefit industry and companies are likely to be cut before the government turns its attention to those that affect consumers, said Alturki. “And even that will be a gradual change.”

The biggest Arab economy has come under pressure as the price of Brent crude fell from above $100 a barrel last year to around $35 this week. The kingdom has led Opec in maintaining output and defending market share against higher-cost producers. Net foreign assets held by the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency slid to a three-year low in October. The country’s benchmark Tadawul All Share Index has declined more than 14% over the past year.

King Salman forged a powerful new economic council, headed by Mohammed bin Salman, after ascending to the throne in January in an effort to centralise and accelerate economic decision-making. There are signs that’s happening. Last month, after years of talks, a new annual fee on undeveloped urban land was approved by the cabinet less than a week after it was passed by the Shura Council, an advisory body.