Reuters

London

For the first time since the financial crisis, investors are starting to differentiate between peripheral eurozone government bonds and corporate credit, thanks to ECB support and growing confidence that Europe’s debt crisis is over.

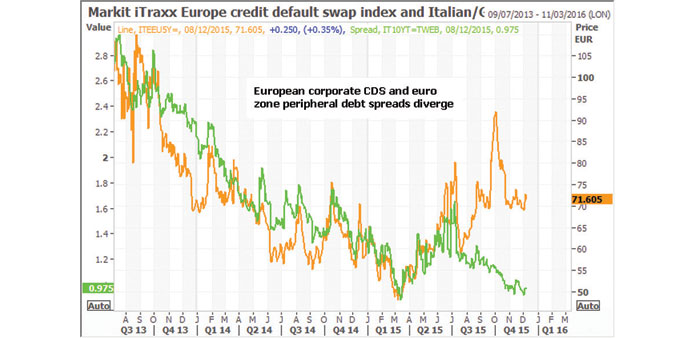

The Markit iTraxx Europe index, which reflects the cost of credit protection on company debt, began to diverge from the eurozone periphery, as measured by the yield gap between 10-year Italian and German government bonds, in the third quarter.

The two had moved almost in lock-step since the height of the eurozone crisis in 2011 as investors viewed the sovereign debt of countries such as Italy, Spain and Portugal as being at least as risky as similarly rated corporate bonds.

A marked divergence has arisen since late July. The iTraxx index, seen as a gauge of corporate credit risk, hit a one-year high in October just as falling peripheral bond yields pushed the Italian BTP spread over Bunds to its narrowest in five months.

The move, say analysts, shows that peripheral government bonds are no longer seen as in crisis mode and likely to be dragged down with risky corporate debt if sentiment towards the latter deteriorates.

“There is a lot of fairly reasonable caution out there about credit markets, partly because of concern that we may be entering a period of lower global growth,” said Giles Gale, head of European rates strategy at RBS in London.

“This shouldn’t colour what you think about peripheral government bonds – they are a very different product, that have different fundamentals and a very significant backer.”

The European Central Bank’s €60bn-a-month asset-purchase programme, launched in March, has pushed bond yields lower across the euro area.

But it is not cited as the only reason why government bonds in some of the region’s most indebted states are now being viewed as relatively safe havens for investment. Improving economic conditions and efforts at structural and fiscal reform have helped the case for the periphery states. Italy completed major employment reforms in September, while quarterly growth in Spain hit its fastest pace since 2007 in the April to June period before slowing slightly since then.

“The creditisation of peripheral bond markets stemmed mainly from fears about a break-up of the eurozone,” said Nicholas Spiro, managing director at Spiro Sovereign Strategy.

“Those fears have receded significantly and convergence is once again the watchword for peripheral bonds.”

RBS says the decoupling between peripheral rates and risk assets could be a major theme of 2016 – just as a decoupling between US Treasuries and eurozone bonds has been this year.

The yield gap between 10-year bonds of Italy and Germany, the benchmark in Europe, is just below 100 basis points, having shrunk from 550 bps in 2011.

The spread between 10-year Spanish and German bonds, currently just above 100 bps, could fall to around 40 bps next year, said Gale at RBS.

For others, the outlook for corporate bonds is a reason to expect the decoupling to continue into 2016.

David Watts, the head of the European strategy team at research firm CreditSights, says the risk factors for credit are outside and not inside the eurozone.

“They are commodities, the Fed hiking interest rates, weak emerging markets and also the wild card of China,” Watts said. “Whereas, up until now, those have all looked like reasonably strong supports.”

He added that while European corporate default rates remained fairly low, sentiment towards the sector has been undermined by defaults in the US.

The European corporate debt market is about €2tn in size – roughly the same size as Italy’s government debt market.

Fitch Ratings said last month that energy and metals/mining defaults continued unabated mid-way through the fourth quarter, maintaining pressure on the default rate among high-yielding US companies.

Concerns about credit markets contrast with general optimism about peripheral government debt.

“There’s better transparency, there’s less crisis about the whole thing,” said Gale at RBS.