Reuters/Shanghai

As Yum Brands looks to triple its store footprint in China and revive flagging growth there, it faces a hurdle with one of its traditional growth drivers: the country’s underdeveloped franchise market.

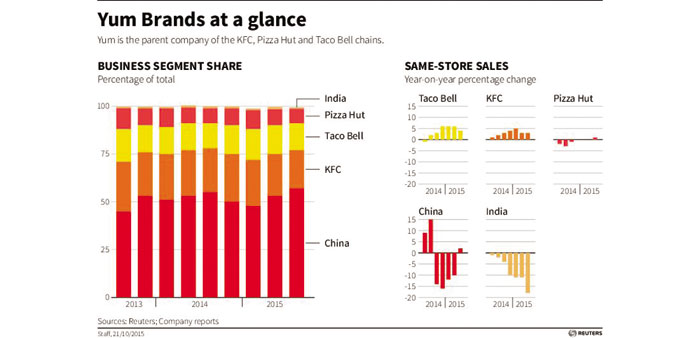

The parent of KFC, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell said this week it will spin off its dominant China business, where it aims to grow its restaurant count to 20,000 and bring in more franchise partners. Nine in 10 Yum stores worldwide are franchised.

China’s franchise market, however, has been held back by food safety worries, opaque supply chains and a lack of reliable partners, meaning companies often resort to managing stores directly. This gives them more oversight, but it raises costs and potentially slows expansion.

“Franchising has always been seen as a more iffy proposition here,” said James Roy, Shanghai-based associate principal at China Market Research, pointing to a lack of large-scale partners, intellectual property risks and food safety fears.

Only 7% of Yum’s 6,900 China stores are operated as a franchise versus 91% outside China. Rival McDonald’s Corp franchises around 15% of its China outlets versus more than 80% globally.

Yum wants to raise its franchises to one in 10 of its China outlets this year. Decisions thereafter will be left up to the spun-off China unit. McDonald’s is moving in the same direction, and said recently it was looking for a buyer for its 400-plus Taiwan outlets.

Franchising has long been a tool to accelerate expansion. In Yum’s 2014 annual report, CEO Greg Creed wrote the firm had “the franchise capability necessary to facilitate growth.”

While the franchise model works well in developed markets, where reliable supply chains ensure food quality, it has less of a track record in China, a vast emerging market where Yum is expanding at break-neck speed and where close control of supply chains is vital for success.

“We have not been approached by Yum to help them expand in mainland China. Even if we had, we would be very cautious. We don’t have the resources and capability,” said a senior executive at Taiwan’s Uni-President China Holdings, who didn’t want to be named.

He noted China is a “tough market” with a focus on food safety, fast rising wages and steep rental costs.

Picking the right partners will be key for Yum to navigate through its toughest period yet in China, where it has been hit by damaging food safety scares, slowing economic growth, rising competition from local rivals and its own marketing blunders.

“There’s no lack of Chinese entrepreneurs willing to invest in a franchised store, but few are competent to manage it,” the US Department of Commerce has warned American firms.

This might mean Yum will need to scout beyond mainland China. It already has ties with Jardine Matheson Holdings, which runs franchises for Pizza Hut and KFC in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Other potential partners could include Uni-President; Singapore’s BreadTalk Group, which operates Carl’s Jr outlets in China; and China F&B Group, which has links with Papa John’s International and Berkshire Hathaway’s ice cream outlet Dairy Queen.

Locally, Beijing Hualian and China Resources Corp help run outlets for international brands.

Or, says Bernstein analyst Sara Senatore, Yum could opt to go it alone. “China still generates plenty of cash and its brand and supply chain have a very broad reach. So from a practical standpoint, it doesn’t need franchisees to expand,” she said.

Coffee giant Starbucks Corp has reduced its reliance on franchised stores in China, now directly managing around 60% of its outlets compared to just 11.5% a decade ago. The balance for Yum to consider is: would the pace of growth be worth the risk of losing control over food safety – a sensitive issue for Chinese diners fed on a diet of horror stories from recycled “gutter oil” to decades-old “zombie meat”.

“If there were any question marks at all over the integrity or trust of the franchise partner, it would make me even more worried than now,” said Li Mengxin, a 22-year-old student in Shanghai.