Agencies/Seoul

The members of families split and then permanently separated by the 1950-53 Korean War carry many sad memories and stories, but few that are as unique and dramatic as Park Yun-Dong’s.

One of the lucky South Koreans selected to take part in a rare family reunion to be held in North Korea next week, the 90-year-old is bracing for an emotional meeting with the family of his younger brother, who died four years ago.

“There won’t be another time. I’m old and I know we won’t be meeting each other again,” Park told AFP in his small, neat apartment in Ansan, about 40km south of Seoul.

“I want to tell them how important it is that the two sides of the family don’t forget about each other,” he said.

“And I want to them to know about the family history, about what happened to us.”

Millions of people were separated during the three-year Korean conflict, which sealed the division between the two countries.

Most died without having a chance to see or hear from their families on the other side of the border, across which all civilian communication is banned.

But Park’s family history is very particular.

He is what is known as a “Sakhalin Korean” -- a community whose ordeal began in the 1940s and outlasted both the Korean War and the far longer Cold War that followed.

Park was born in 1925 in Pyeongchang, now a well-known ski resort in the east of South Korea which will host next year’s Winter Olympics.

At the time, the Korean peninsula was under Japanese colonial rule and when he was 18, Park was among 150,000 Koreans forced to relocate to Sakhalin — an island off the far eastern end of Russia — to work in coal mines and lumber yards providing raw materials to fuel Tokyo’s World War II efforts.

In the end his entire family relocated, including his parents, three brothers and younger sister.

Days before the Japanese surrendered in 1945, Soviet troops took over the island, and Park and his family suddenly found themselves — and their fate — under new administration.

The Japanese on Sakhalin were repatriated and nearly two thirds of the Koreans on the island joined them in the hope of finding opportunities in Japan’s post-war reconstruction.

The roughly 43,000 Koreans who wanted to return home faced a dilemma as the Korean peninsula was now divided along the 38th parallel into the Soviet-controlled North and US-controlled South.

As the division hardened and then cemented with the Korean War, the plight of the Sakhalin Koreans became starker.

The Soviet Union had no diplomatic ties with the South Korea and — with the Cold War gathering pace — Seoul was wary of allowing back thousands of people whose loyalties might not be guaranteed.

“So, the only return option was to North Korea,” said Park.

And that was the option his younger brother took, moving to the North in 1960 to study medicine.

In the hope that the political winds would shift, the rest of the family stayed, embarking on what would turn into half a century of stateless exile on Sakhalin.

“We felt totally abandoned,” he said. “Our one desire was to go home, but our homeland refused us.”

Only when the Soviet Union collapsed did things begin to change and Park, along with his two remaining brothers and sister, finally moved back to South Korea in 2000.

After his two brothers died, Park’s thoughts increasingly turned to his younger brother in North Korea who, he discovered through relatives who remained in Sakhalin, had qualified as a doctor and was married with a son and daughter.

“When I learned he had died, I got a pain in my chest that has stayed with me ever since,” Park said, fingering an old family photograph from the early days on Sakhalin.

His brother’s children are now in their 40s and it is they who Park, accompanied by his sister, will meet next week at the reunion in North Korea’s Mount Kumgang resort.

“They are like my own children and I worry about them. I’ve heard they have had problems making ends meet,” said Park, who has prepared care packages of winter clothes as a gift.

The reunion time is extremely limited, with each family only getting a few hours a day together over a three-day period.

“It’s not nearly long enough, but I believe I will feel more comfortable, more at ease with myself after seeing them,” Park said.

“I would like to tell them: ‘Take care and be healthy’.”

When Ahn Yoon-joon, 86, meets his two younger sisters this week that he has not heard from in more than 60 years, there is much they won’t be able to talk about.

A guide book distributed to the elderly South Koreans chosen by lottery to meet family members separated by the 1950-53 Korean War includes a long list of do’s and don’ts - mostly don’ts.

“You can’t ask everything you want to ask. This is not a reunion, but just a meeting that’s staged,” said a frustrated Ahn, who missed out in lotteries for past reunions and said the restrictions have dampened his enthusiasm for the upcoming trip.

The booklet provided by the Red Cross, which organises the reunions, advises South Korean participants not to press for answers on topics such as the North’s political leadership or living standards.

“In case your family members from North Korea sing propaganda songs or make political statements, please restrain them and try to change the subject,” the booklet advises.

Ahn wants to ask how his father died, but realises it could be politically sensitive for his sisters to answer, as their father was a rich landowner in what became militantly socialist North Korea.

“All I can do is to take down the dates my parents died. There’s nothing else,” he said.

At the outbreak of the Korean War, Ahn, then an elementary school teacher, fled his hometown, fearing North Korean communist forces would conscript him or kill him.

The two Koreas, bitter rivals that remain in a technical state of war, agreed to hold family reunions for the first time since February 2014 after negotiating the end of a standoff at their heavily militarised border.

Under UN Security Council resolutions imposed after the North’s missile and nuclear tests, only gifts worth 100,000 South Korean won ($88) or less are allowed.

Ahn first thought of a gold necklace for each of his two sisters but since jewellery is banned, he will bring medicine and toothpaste.

The reunion of 90 South Koreans and 96 North Koreans, the 20th of its kind, will be held at a resort in the North, mostly in a large ballroom under the watchful eye of officials.

The reunions are politically important for the South, where 66,000 people are on a waiting list to see long-lost relatives, a number that is shrinking fast, while the North also seeks to maximise their domestic propaganda value.

Kim Woo-jong, 87, who fought for the South after fleeing the North in 1951, leaving his mother and sister behind, said he will watch what he says during the reunion with the sister he calls “the flower of the family.”

“My history looks bad to North Koreans,” said Kim, partially paralysed by a stroke more than 30 years ago. “But my sister is taking the risk to meet me before we die.”

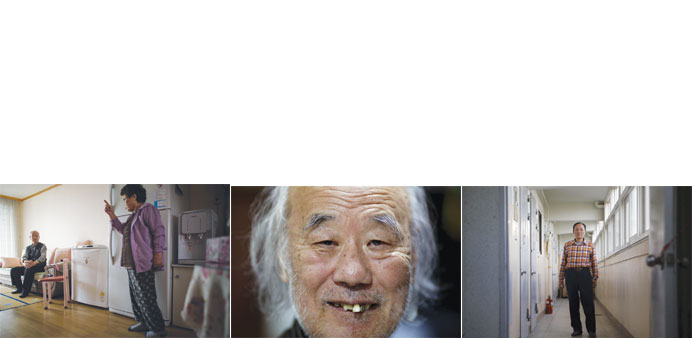

From left: Park Yun-Dong, 90, with his wife in his apartment in Ansan, south of Seoul. Kim Woo-jong, 87 and Ahn Yoon-joon, 86, who have been selected