Bloomberg

New York

In the year since Treasuries suddenly went haywire in the bond market’s version of the “flash crash,” unusual bursts of volatility have become more common than ever before.

The $12.9tn US government bond market - long considered the deepest and most liquid in the world - is now plagued by more bouts of turbulence than at any time since at least the 1970s. By one measure, outsize swings are occurring almost twice as often as statisticians would normally expect, according to data compiled by TD Securities.

“This isn’t your grandfather’s market anymore,” Steven Meier, the head of cash, currency and fixed income at the money- management unit of State Street Corp, which oversees $2.4tn, said from Boston.

A common refrain is that rules intended to limit financial risk-taking have made Wall Street bond dealers far less willing to make markets in Treasuries, which has exaggerated price swings and led to brief periods of illiquidity as investors try to decipher the Federal Reserve’s intentions on interest rates.

But perhaps just as important is the rise of lightning-fast computer trading, which has caused Treasuries to behave more like equities and raised thorny questions about the underpinnings of the world’s risk-free asset.

Researchers at the New York Fed said they found evidence that high-frequency traders may be creating an illusion of liquidity, especially when investors look to move large blocks of Treasuries.

While nobody is saying the US government bond market is broken and New York Fed researchers also concluded that HFT firms bring more accurate pricing and reduce the cost of trading, the stakes are high. Any worries about undue volatility in Treasuries have the potential to threaten confidence in a market that’s the benchmark for borrowers everywhere in the world.

And as the Fed moves closer to ending its near-zero rate policy, the potential for more disruptions akin to what happened on October 15, 2014 - when a flurry of trading by HFT firms fueled a 0.16 percentage point plunge then rebound in 10-year yields in a 12-minute span - has become a pressing concern for investors and policy makers alike.

“Liquidity is an issue when the algos kick in and do crazy stuff,” said Stewart Taylor, a money manager at Eaton Vance Corp, which oversees $313bn. Although they’ve pushed the cost of trading lower, “to me, it’s not really worth the trade- off. For someone who legitimately has trades to do, you can’t execute quickly enough anymore.”

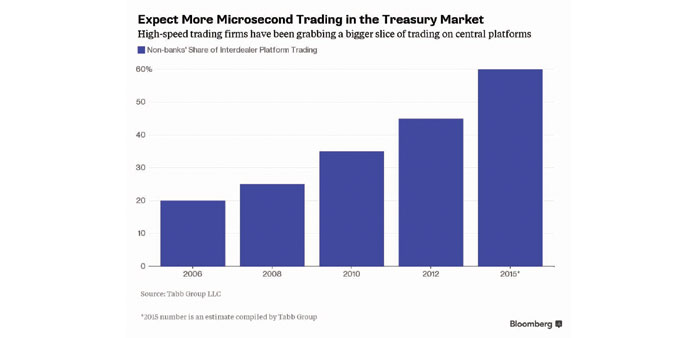

Ultra-fast moving firms, which typically trade Treasuries in microseconds using sophisticated computer algorithms, account for at least half the transactions on electronic platforms, research firm Tabb Group said in a July report.

A decade ago, much of Treasury trading was done over the phone with Wall Street bond shops.

The trend toward automation, and away from human traders, might be spurring big swings in Treasuries to occur more often, according to TD.

Daily moves in 10-year Treasury yields have exceeded one standard deviation - which is equal to about 3.4 basis points, or 0.034 percentage point - about 58% of the time this year.

That’s the highest reading going back to 1975. Based on a normal range of probabilities, moves of such magnitude should only occur 32% of the time.

The dislocations are so prevalent that they even exceed that of US stocks, and is an “ominous” sign that bond market liquidity is impaired, according to TD’s Priya Misra.

“Volatility is here to stay,” said Misra, the head of global interest-rates strategy at TD, one of 22 primary dealers that trade directly with the Fed. “Nowadays, you’re getting bigger moves than you were before.”

In addition to the New York Fed’s finding that rapid-fire traders are making it hard for investors to assess market depth, the International Monetary Fund also noted that on October 15, they triggered a “feedback loop” in Treasuries, where HFT firms trying to reduce risk beget more volatility with more trades. Increasingly, the turbulence buffeting Treasuries has little to do with what’s actually going on in the US, as financial stress spills over from one asset class to another and into different global markets, according to the IMF. And that comes just as investors are trying to figure out exactly when the Fed will raise rates.

“We’re looking at everything now,” State Street’s Meier said. “Treasuries versus other sovereign debt - and dare I say, even Chinese stock prices - for indications of normalcy or extreme levels of volatility.”