Bloomberg/Washington

Wall Street is close to cutting billions of dollars from the cost of a derivatives rule as a debate among regulators over how tough the provision should be shifts in banks’ favour.

Firms such as JPMorgan Chase & Co and Morgan Stanley wouldn’t have to set aside as much money in trades between their own divisions in the final version of a rule US regulators may release as soon as next month, said two people familiar with the discussions. After months of disagreement, the agencies, which include the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp and Federal Reserve, decided to ease the demands of an earlier version of the proposal, according to the people.

The industry had fought the mandate that both a bank and an affiliate put up collateral, which was laid out in the version of the rule that was proposed last September and had strong support from the FDIC.

In a compromise, banking regulators now agree that the final measure should only demand collateral from an affiliate trading with a US bank unit, said the people, who requested anonymity because the rule hasn’t been released publicly.

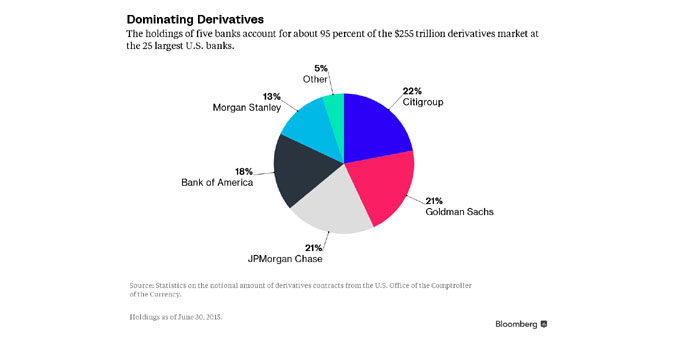

That means the US banking divisions of the biggest swaps dealers, such as Citigroup, Goldman Sachs Group, JPMorgan, Bank of America Corp and Morgan Stanley wouldn’t have to pledge collateral to offset risks from non-cleared swaps with their overseas affiliates, such as a UK brokerage.

It’s difficult to estimate how much is at stake for the banks given the complexity of the market. Under last year’s proposal, banks and their affiliates would have had to set aside tens of billions in collateral.

That’s a slice of about $644bn in collateral that would be held by banks in all non- cleared swap trades, according to preliminary estimates from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Supporters of the more stringent version said demanding assets from both sides for every transaction would help shield parent companies from risky trading at affiliates that are less regulated and capitalised. Bankers argued that swaps transactions with their own divisions are a way to hedge risks and it’s unnecessary for both sides to set money aside when the firms are trading internally.

Swaps trading - when it was largely unregulated - amplified the financial crisis seven years ago. FDIC Vice Chairman Thomas Hoenig has argued recently that riskier trading at banks needs to be insulated enough that taxpayers don’t have to prop them up again in a failure.

The firms have typically done these trades to transfer risk from their affiliates to their deposit-backed banks, where they enjoy better borrowing rates. Current practice doesn’t call for as much collateral in these transactions.

The agencies have also decided to require that the US bank units keep a record of what they would have posted if they had to set aside collateral as well, one of the people said, which may placate those who preferred margin posted by both sides.

Spokesmen for regulators involved in the rule, including the FDIC, Fed, OCC and Commodity Futures Trading Commission, declined to comment. The CFTC, which along with the Securities and Exchange Commission is supposed to provide a parallel version of the bank regulators’ measure, is aiming to complete its rule as soon as next month as well.

Requiring collateral between a company’s own divisions was the major outstanding conflict within a broader rule governing collateral for non-cleared swaps. The battle has dragged on since the Dodd-Frank Act called for the change in 2010.

While banks would rather be exempt from holding collateral when trading with their affiliates, it’s still preferable if they can cut the two-way requirement down to one-way, said Donald Lamson, a lawyer at Shearman & Sterling and a former OCC official.

Subjecting banks to a tough collateral demand would “increase costs that will be passed onto consumers, increase complexity and ultimately it will impede proper allocation of risk in the market,” Lamson said in an interview.