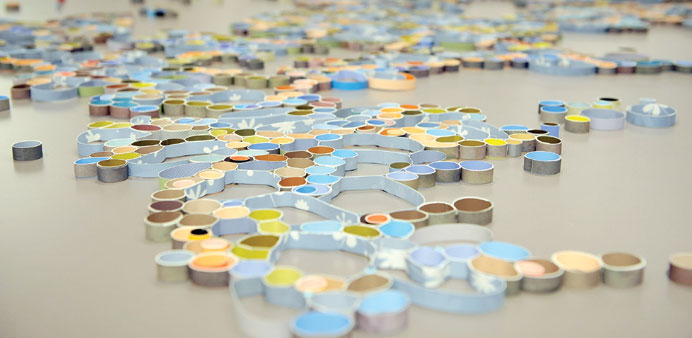

REFLECTIVE: Canadian artist Michelle Forsyth’s work that recreates an oil film created on water as a reference to the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska she had witnessed.

By Anand Holla

On a large white wall, page after page of a seedy romance novel are bound together in a sequence by long stretches of gold thread. Much of this giant collage of a poster is delightfully carved such that it could only be the work of a mythical silverfish possessing magical powers — or an accomplished paper-cutting artist.

Fortunately for us, it happens to be the latter. American artist Lauren Scanlon is the mind behind this striking piece of art, which along with other exquisite hand-cut paper works by an international roster of artists, is part of a new exhibition.

Titled Papercuts, the exhibition is up at the Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar (VCU-Q) Gallery until October 15.

American artist Reni Gower, who is also the curator of the exhibition, turns to Scanlon’s work to explain. “These pages are of a book named Gates of Steel, which belongs to this American genre called Harlequin romance novels. These books are pretty raunchy and aren’t very complimentary to women,” says Gower.

“Lauren took the whole book apart and then sewed it all back together, page by page with golden thread, and then cut this beautiful pattern into it. While this particular piece first started as a way to censor and be didactic, it later became celebratory and retold the story,” explains Gower.

Like most visitors would, Gower finds the “dichotomy” between something that’s dirty and something that’s quite beautiful rather interesting. The works of Gower and Scanlon are joined by those of Jaq Belcher, Béatrice Coron, Michelle Forsyth, Lenka Konopasek, and Daniella Woolf.

All the artists have used various kinds of tools and paper to create works “that range from narrative commentaries to complex structural abstractions.” Their works, says VCU-Q, are bold contemporary statements that celebrate the subtle nuance of the artist’s hand through a process that traces its origins to 6th Century China.

A professor in the Painting and Printmaking Department at Virginia Commonwealth University in US, Gower has more than 30 years of professional experience in the fine arts.

“I kind of stumbled upon Papercuts when I needed a quick solution to make a big piece that was as complex as my paintings,” says the artist whose work has been exhibited in Qatar, UAE, Australia, Italy, Peru, Korea, Israel, Belgium, England, Moldova, and Moscow.

It was when Gower was teaching summer school in Scotland that the idea rushed to her. Asked to do an exhibition on an awfully tight deadline, Gower had to repurpose the Celtic knot-work patterns that she had been studying. “I figured I could make something big if I cut it. I don’t know where that idea came from. But I started looking at other paper-cutting work. Suddenly, it was an exciting thing to pursue,” she says.

Soon, Gower began exploring the realm of contemporary paper-cutting. “At the same time, a couple of museum shows had mounted exhibitions on works cut in paper,” she recalls, “So I started doing research, trying to find a way to pull together some work that didn’t duplicate those at the other exhibitions.”

When Gower came across Belcher’s and Coron’s works, she sought their collaboration and they agreed. Soon, Gower found other artists who, too, “brought something different” to the table. Light, shadow, and colour play key roles, says Gower, transforming this ancient technique into dynamic installations filled with delicate illusions.

What united the ladies was that everything they made was hand-cut. “It’s very important that it’s not laser-cut and that the hand is very invested in the work. For all of us, it’s very much about the process, the ritual, the quieting of the mind, and to stay in the moment so you can do the cutting,” says Gower, “It also hopefully transcends to the person looking at it, so it becomes a private space within a public space that allows you to become contemplative or meditative.”

Whatever the structural integrity of the paper can handle, you can create, says Gower. “So you must experiment. Paper is pretty resilient, pretty strong and very affordable.” Sometimes though, you need more than regular paper.

French artist Coron’s work, for instance, uses Tyvek, which is a tough, durable nonwoven DuPont-manufactured sheet consisting of spun polyester fibre that’s used in construction. “If this was done in paper, it would have been torn. Since Tyvek allows you to make tiny threads that don’t tear, Coron could leave all these little, delicate strings here,” Gower says, pointing to Coron’s exceptional examination of multiple levels of society steeped under a city.

In fact, as Gower points out, multi-layered narratives surface in each work on display at the gallery, and there are surprises. “They may look playful and childlike in some ways, but stop scratching the surface and there are sub-stories,” Gower explains, as she gazes into Coron’s haunting story-telling canvas of expansive black sheet of hand-cut Tyvek, “You see, there are skeletons, Day of the Dead celebrations, and bank robberies breaking out.”

Coron’s work is based on Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities. Gower says, “It’s about cities built out of garbage and the subterranean worlds. It’s a lot about urban culture and all the opposites in the world like heaven and hell, free will and fate, light and dark.”

Forsyth, a Canadian artist, has recreated an oil film that forms on top of water, using paper, watercolour, screenprint and ColorAid paper. The scattered bubbles-like work simulates the tragic Exxon Valdez Oil Spill in Alaska on March 24, 1989, in which 250,000 barrels of oil were lost, fouling around 1,300 miles of coastline. “She experienced it as she grew up on a sailboat,” Gower says, “This, like a lot of Forsyth’s works, is such a beautiful and decorative work but has a catastrophic reference to it.”

An indoor tornado whipped up by Konopasek, a Czech artist, using cut white paper, wire and small figures, is an eye-catching installation of mesmerising destruction.

“This artist uses tornado as a symbol of violence but also as the seductive beauty of violence,” Gower reasons, “When the tornado is sweeping through, wherever its little whipping tail touches ground, it unleashes havoc. If you have ever witnessed that tail of the tornado in action, you will know that it’s horrifically scary, and yet you can’t take your eyes off it. You are totally seduced by it even though you are probably in great danger.”

In four years, Papercuts has been shown at 12 venues — Doha being its last stop. “We first opened it in Alabama and then it travelled all over the US before coming now to Doha,” says Gower.

The warm reception for the exhibition here reaffirms Gower’s belief in art. “This heartening response means that we can communicate across cultures through the visual and the arts. We don’t have to be at odds just because we speak different languages or come from different backgrounds. We really can have a very productive, enlightening and positive experience through the arts. And that’s the goal.”

What does she make of the recent surge in paper art? Gower says, “I think we are so saturated with technology that we are removed from the physical and people are really craving a way to put their hand back in. Paper is cheap and can be very forgiving. If you make a mistake, you can throw it in the thrash. It’s a way for people to just have that physical interaction with their world again.”

Gower continues, “I don’t think we should get rid of technology, but we also shouldn’t get rid of our hand just because we have a computer. There’s a physical need that people really crave to touch things and create things through touch.”

For Gower, the effect is therapeutic. “Paper-cutting really calms me down. Sometimes I can’t think about the other things because I have quieted my mind so much that all the hurly-burly rat-race of the day just drips away.”

However, Gower must focus. She can’t “just willy-nilly go in there and cut.” She says, “I have to be really in tune to what I am doing or I’ll make mistakes or hurt myself,” she says. Papercuts can hurt quite a bit.

“I have never cut myself though,” she mentions. “Oh please, don’t make that the last line of our conversation,” she says and laughs.

Too late, Miss Gower.