By Arno Maierbrugger/Gulf Times Correspondent /Bangkok

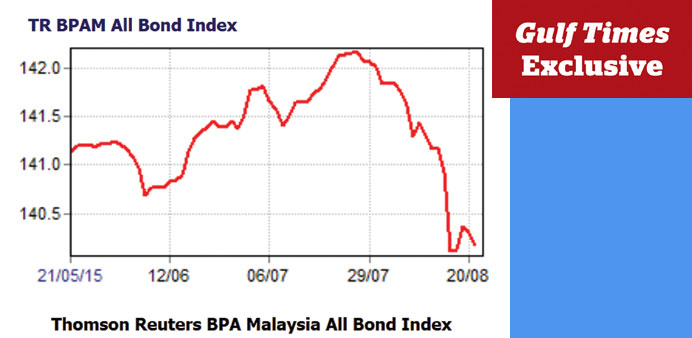

The broad sell-off triggered by the continued stock market slump in China is rattling across Southeast East Asian economies. In particular, the Malaysian bond and sukuk market has been badly hit by selling pressure, causing yields to surge and bonds indexes registering their biggest losses year-to-date.

Malaysia, the world largest sukuk issuer, is under particular and multiple pressures. Not just the weakening economy in China, one of its largest trading partners, is stepping on the brakes of Malaysia’s economic growth, it is also the rapidly falling value of the country’s currency, the ringgit, the tumbling oil price – a major setback for Southeast Asia’s largest oil exporting nation –, heavy capital outflows, as well as Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak being embroiled in controversy over alleged misallocation of funds by state-owned investment firm 1Malaysia Development Berhad, which has built up some $11bn in debt.

Of Malaysia’s four outstanding dollar-denominated government sukuk only one due 2016 is in the green since April with a meagre 0.3% as per the end of last week, while the others, due 2045, were down between 0.24% and 3.6% in the period. Heavy selling pressure was triggered mainly due to the continuous depreciation of the ringgit against the US dollar. Since April alone, the ringgit dropped 13%. Sukuk sales in Malaysia fell 34% to $6.5bn at current rates so far in 2015 from a year earlier, while the nation’s Islamic banking assets have reached a record of around $150bn in dollar terms – which brings with it an ever-increasing obligation to return profits to investors.

Economists say that this situation – a multitude of negative macroeconomic factors – will show whether the notion is true or not that sukuk and other Shariah-compliant investment instruments are more stable and reliable in times of market turmoil than conventional finance products.

For example, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is actually endorsing Islamic finance as an alternative to conventional finance, it is also sending out warning signs.

“Islamic finance may help promote macroeconomic and financial stability,” argues Christopher Towe, deputy director at the IMF’s monetary and capital markets department, adding that “the principles of risk-sharing and asset-based financing can help promote better risk management by both financial institutions and their customers, as well as discourage credit booms.”

However, the global lender also warns that, with the Islamic finance industry being relatively young, there are also “systemic vulnerabilities” especially in case Islamic finance does not fully fulfil its key criteria to be truly asset-based and the requirements for risk-sharing. Other systemic risks remain liquidity-related, mainly stemming from a shortage of tools for short-term funding of Islamic banks, and with it a limited scope of Shariah-compliant financial safety nets for banks, Towe said.

When problems in the financial markets congregate like they do in Malaysia this year – falling oil prices, falling prices for other export commodities, weakening trade with China, capital outflows as the US prepares to raise interest rates, massive slump of the domestic currency’s value, dwindling currency reserves, a bearish stock market, and on top of that a loss in confidence in the government’s ability to properly manage public finances, then this is a matter of real concern for a country that is heavily reliant on Islamic finance-based debt. Higher borrowing costs – unavoidable at the current state – would make it much more expensive and thus highly risky, if not unaffordable, to finance the government’s ambitious $444bn development plan to build rail, roads and ports as it seeks to become an advanced economy by 2020, a core strategy of the current government.