By Andy Home / London

You don’t hear so much about the load-out queues in the London Metal Exchange’s (LME) warehouse system these days.

It’s not that the queues to take delivery of aluminium from Detroit and Vlissingen have disappeared.

As of the end of last month the waiting time at Detroit was still 328 days and that at the Dutch port 327 days.

But it does seem that the LME, stung by fierce criticism from its manufacturing users and pressured by regulators on both sides of the Atlantic, has finally found the right combination of measures to get the queues under control.

Both aluminium queues have been steadily falling over the last few months and the exchange’s many critics have been assuaged by its prognosis that a new raft of rule changes will cause waiting times to fall below the targeted 50-day threshold around May next year.

The landscape of the LME’s warehousing system is already starting to change in anticipation of a post-queue environment.

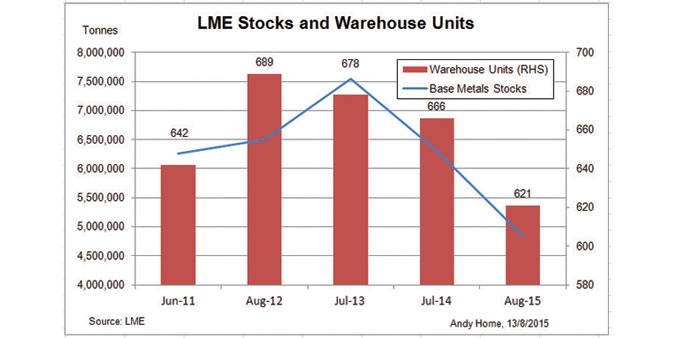

The number of warehousing units has been falling. There are currently 621 (excluding steel storage compounds), which is the lowest tally in at least five years.

That’s a simple reflection of the amount of metal that is being forced out of the delivery system by the exchange’s targeting of the queues. Total registered base metals tonnage has fallen from a peak of 7.6mn tonnes in mid-2013 to a current 4.8mn tonnes.

The composition of warehouse operators is changing fast too with some of the bigger players drastically reducing their foot-print while new companies move in to try and take advantage.

This is still an evolving process.

So far at least, the dominant warehouse operator, Pacorini Metals, owned by physical trading powerhouse Glencore, remains defiantly dominant.

The original queue was the brain-child of Metro International, which at one stage had a near monopoly on LME storage in the city of Detroit.

Detroit was inundated with aluminium after the Global Financial Crisis but the flood of arrivals turned to a trickle of departures when stocks financiers wanted to move large tonnages to cheaper off-exchange storage.

Metro’s strategy, exploiting outdated and inefficient LME load-out rules, was finessed by Goldman Sachs when it bought the operator in 2010.

Goldman has now departed, selling Metro to the Reuben brothers, and the Detroit aluminium mountain has been whittled down to a foot-hill.

Metro’s LME warehousing operations have subsequently been much reduced. It now operates 66 units, compared with 93 a year ago and 105 in 2013, having all but left locations such as New Orleans and Port Klang in Malaysia.

Not that it’s quietly slunk off into the twilight zone of the Reubens’ property development portfolio. It remains an LME warehousing force to be reckoned with.

The LME’s July report detailing stocks storage by operator showed Metro warehouses in the South Korean port of Busan receiving 73,725 tonnes of metal last month, confirmation that it was the prime beneficiary of the mass raid on LME lead stocks earlier this year.

An even more dramatic retreat from the LME storage business has been effected by Impala Terminals, owned by commodities house Trafigura.

After a failed attempt to recreate Metro’s queue model at Antwerp, the number of Impala sheds has shrunk from 41 two years ago to just nine.

Henry Bath, sold last year by JP Morgan to Mercuria, was never in the queue game but it too has slimmed down dramatically, cutting the number of registered storage units by 21 to 49 over the last 12 months.

As such big names withdraw, others are beefing up their LME storage presence.

Worldwide Warehouse Solutions (WWS), the logistics arm of trade house Noble Group, has been steadily building out its presence. It now operates 24 units, up from 13 two years ago.

After first muscling into Metro’s home turf in Detroit, it has broken into Pacorini’s Fortress Vlissingen, where it now operates seven sheds and as of last month was storing 37,118 tonnes, much of it also lead thanks to the same stocks swoop that benefited Metro in Busan.

BTG Pactual, part of the Brazilian investment bank, is another player on the up, adding 10 units, nine of them in Rotterdam, over the last year.

But perhaps the two most interesting arrivals are a couple of old LME warehouse faces.

After selling its LME warehousing business to Glencore back in 2010, the original Pacorini group has returned to the LME fray, opening 11 units over the last year.

Now trading as B. Pacorini SRL, and not to be confused with Pacorini Metals, it has established a presence in all three major geographic regions; Antwerp and Spain in Europe, Busan and Gwangyang in Asia, and Mobile and New Orleans in the US

♦ Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The opinions expressed are his own.